I found paradise and hell all in the same trip to Europe. Of course, many Americans enjoy visits to European cities such as London and Paris. But the parts I enjoyed most were the rural areas.

In April, 2005, inspired by some expiring frequent-flyer miles and the fact that a colleague of mine, Wendell Cox, was teaching in Paris and had a spare couch for me to sleep on, I decided to take my first trip to Europe. I ended up spending eleven days in four countries, including a day walking in Paris, four days taking trains through Italy and Switzerland, and five days driving through France and Germany (passing through Belgium and the Netherlands along the way).

My personal goals in taking this trip were to do some railfanning, see the Alps, and scout out a possible future bicycle trip. My professional goals were to see how Europe is suburbanizing and using various modes of transportation. While I have data on these changes, it is always nice to see it first hand. Thanks to the wonders of digital photography, I managed to take nearly 400 photos a day, of which about 1-1/2 percent will be in this travel log

Wendell met me at the plane on April 20 and, after taking an "RER" train and dropping my bags at his flat near the Gare d'Austerlitz, we went on a walking tour of Paris. After seeing the Notre Dame Cathedral, Eiffel Tower, and Arc d'Triumph, we took a train six kilometers to La Defense, a skyscraper-filled edge city built by the government to house many of its offices.

La Defense has its own arch, La Grande Arche, which has about the same proportions as the Arc d'Triumph but is actually such a gigantic office building that the entire Notre Dame Cathedral could fit within its frame. La Defense also had a large, American-style shopping mall.

Next day I took a TGV from Paris to Turin, Italy. Getting to Turin meant going over the Alps. TGVs are fast, but like American trains, people focus on the top speed without thinking about the average speed. Once we hit the mountains, the train went no faster than an American train in the mountains.

I was surprised to learn that Turin used to be the home of the Italian royal family. I didn't even know Italy had a royal family. That evening, I had dinner with a colleague named Francesco Ramella, shown in the photo with his beautiful girlfriend, whose name sounded a lot like Liza (sorry if I got it wrong).

Then I took a train to Milan where I bumped into a woman walking a Belgian sheepdog, similar to my dog Chip, except all black. In the United States, Chip is a "Belgian Tervuren," while this black dog is a "Belgian Groenendale," but in Europe they are both called "Berger Belge" or "Belgian Shepherds."

In Milan I also went to the Swiss travel office to plan my rail journey in Switzerland. I had done only a little research prior to leaving the states, but knew I wanted to take some scenic trains and in particular one called the Centovalli. But a friend of mine named Dave Schumacher urged me to take the Glacier Express, Golden Pass, and Jungfrau instead.

The brochures in the Swiss travel office didn't help much because, for some reason, they were all in Italian. I also had no idea how big Switzerland was -- when I got back home, I looked it up and realized it is the same size as West Virginia. But the maps of all the rail lines made me think I couldn't possibly take all the scenic trains in just four days.

The woman said, "If this is your first trip to Switzerland, you have to take the Jungfrau." So we planned a trip on several trains that included a day in a town called Interlocken where I would take a train trip to a high-elevation pass known as Jungfrau. This meant giving up the Centovalli.

First step was an Italian train to the border town of Tirano. The train went through many beautiful little towns and by a large lake, but I didn't figure out until near the end of the trip that I could open the windows to take photos -- something unheard of in most Amtrak trains.

The Swiss train at Tirano was as different from the Italian train as day from night. While the Italian train was cream-and-institutional-green colored under a layer of dirt and the windows translucent with dust, the Swiss train cars were bright red and the windows so clean you could eat off of them.

For me, Switzerland was paradise. Every time I thought I had seen the most incredible things, it surprised me with something new. I used to think the White Pass & Yukon Route was one of the most spectacularly scenic rail lines in the world, but I soon realized that it paled in comparison with this Swiss train. The tracks were meter gauge, and the train made numerous loops including a complete spiral.

I later learned that Swiss rail engineers had built numerous spirals that, like the Canadian Pacific's spiral tunnels, were mostly underground. This was the only one in Switzerland that was completely exposed. Unlike the Williams Loop on the old Western Pacific or the Tehachapi Loop on the old Southern Pacific, this one was small enough to easily see all at once.

This trip ended at St. Moritz, a ski town reminiscent of Vail in that it was filled with skyscraper condos and hotels. I spent the night there and had my only decent pizza in Europe at a hotel restaurant.

Next morning I boarded the Glacier Express, which for 75 years has been carrying passengers from St. Moritz to Zermatt. The cars were again bright red, but I soon learned that this was the color of the tourist trains; most ordinary Swiss trains were cream-and-brown. The first-class cars had huge windows that did not open, which almost made me prefer second class's smaller, but openable, windows.

The Glacier Express is a joint operation of three privately owned Swiss narrow-gauge lines. On board, I met several other interesting parties, including Aoki and Miki, two Japanese tourists. They were going all the way to Zermatt where they would see the Matterhorn. I planned to get off in a town named Brig so I could take other trains to Interlocken.

Along the way we climbed lots of steep routes and I was startled to realize that on some of the steeper grades the route had a third rail that was toothed so that the locomotive and, from the sound of it, each car could engage a cog used for traction and braking. Technically, this is known as a "rack" railway. I had seen cog railways in Colorado, but the only rail line I had heard of that freely switched between racked and unracked was a long-gone route in New Zealand.

At the highest elevation of 6,670 feet the land appeared to be under a permanent glacier. While I imagine most of the snow would melt in the summer, I could see many glaciers from the car windows. At some point in our westward journey we went over the 9.3-mile Gotthard Tunnel, which carries trains north and south through the mountains.

All the way from the St. Moritz to Brig, except at the highest elevations, I could see clear signs of what Americans would call urban sprawl. Lots of old villages had lots of new homes, and many of the homes were not on small lots. Instead, they marched up hillsides in parcels that often seemed as large as 5 or more acres. The Swiss did not appear to have the strict land-use regulation found in other European cities.

The Swiss even had trailer parks -- and I would see some in other European countries too. A few data: Switzerland has about 7 million people and, like many other European countries, its population seems to peaked and is expected to decline slightly in the next twenty years. Its overall density is about the same as New York state, and quite a bit less than Maryland, Connecticut, or Massachusetts. Many big-city Swiss live in apartments, but obviously lots of them have second homes as well.

The Brig station was interesting in that the narrow-gauge private railroad stopped in front, practically in the street, while the standard-gauge government-owned passenger trains converged on more typical platforms in back.

Thus I boarded my first non-private Swiss train. The cars were more sedate than the Glacier Express, but some of the windows still opened. We made a couple of switchback loops climbing above the valley and then descended into Spiez, where I made an across-the-platform transfer to a train to Interlocken.

While the Glacier Express was, at times, filled with lots of passengers, the standard-gauge trains I rode were nearly empty. Most cars had two compartments, one for smoking and one for non-smoking, and I was nearly always able to find an empty compartment, if not a completely empty car, where I could open windows for photography without bothering other passengers.

Interlocken has two train stations, the main one being Ost, but I made the mistake of getting off at the West station. While the weather had been sunny for the last two days, it was starting to cloud up, and I was again doubting the wisdom of going up the Jungfrau, which Dave had said would only be spectacular on a sunny day. I asked at the ticket office and they said my Eurailpass wouldn't cover a trip on the Jungfrau, so it would cost me about $115.

So I decided to change my itinerary and go back to Brig so I could take the Centovalli the next day. I still didn't realize how small Switzerland is; I could have stayed in Interlocken and still made the first morning Centovalli train.

On the way back to Spiez, the train went through a small town and I saw a sign on a house saying, "International Youth Hostel." I am afraid I was too timid to get off, but I checked the schedules and decided to get off at the next town and take the next train back. The hostel was in a town called Leisegen and it was right on the Thuner See (lake).

Though a tiny resort town, Leisegen has hourly service to Spiez and Interlocken during daylight hours. So I planned to take a 6:30 am train to Spiez, catch a train from there to Brig, and a train from there to Domodossola, where I would catch the Centovalli train. The youth hostel people fretted over the fact that my early departure meant I would miss the breakfast that was included in my room price, so they gave me a bag with some delicious bread and fruit. They also told me that this particular hostel was originally the vacation home of the inventor of Ovaltine, which explained why the building had so many vintage ads for Ovaltine in frames. Best of all, the house was next to the railroad tracks, so I could hear trains go by all night long.

The sun hadn't yet risen when I walked to the Leisegen station. The two trains from Leisegen to Brig were routine, but the Brig-to-Domodossola train was the Cis Alpino, a high-speed "pendulum" train connecting Basel with Milan. As soon as we left Brig, we entered the 1921 Simplon Tunnel, which told me this was the route of the old Simplon Orient Express. This tunnel is about 12 miles long, and even after we emerged the route went through so many shorter tunnels that I felt were were in the dark more than in the daylight.

At Domodossola I followed signs to the Centovalli train, which was in a tunnel under the rest of the train station. The train was, in fact, little more than several streetcars hooked together. Domodossola is in Italy and half the Centovalli route is in Italy, so the train I boarded was an Italian train -- which meant dirty windows.

I soon saw that the Swiss had their own Centovalli trains, newer and with cleaner windows. But at least the windows on my train opened.

From a map on the train, I could see the Centovalli route is all of 55 kilometers. The trip takes two hours, meaning an average speed of 20 miles per hour. Centovalli means hundred valleys, and the train passed over numerous stone arch bridges along its route over the mountains and down a deep canyon. It was raining much of the day and I was certain I was having a lot more fun here than if I had gone up the Jungfrau.

The Centovalli ended at Lucarno, where I got on a local train to Bellinzona. From there I caught an intercity train to Lucerne. Though standard gauge, this route had numerous spiral tunnels and switchback loops. It also went through the 9.3-mile Gotthard tunnel. Switzerland is currently building a new, 35-mile rail tunnel under St. Gotthard Pass.

Except Geneva, Lucerne was the only large city in Switzerland I would visit. I had a couple of hours before catching a train to Interlocken and walked around the old town, which was a high-density area of narrow streets. This was clearly a major tourist attraction.

It wasn't long before I wandered into a neighborhood of single-family homes, many of which had garages and large yards. Except for slight variations in building style, I might have been in an old Portland neighborhood.

While the Glacier Express is world famous, competing with it for tourist business is the Golden Pass route connecting Lucerne with Montreaux, in the French part of Switzerland. Like the Glacier Express, the Golden Pass route operates over three different railways, at least two of which are private. However, the middle segment is standard gauge, so passengers have to change trains at Interlocken and a town called Zweisimmen. (I understand they are planning to build a narrow-gauge line from Interlocken to Zweisimmen to close this gap.)

I decided to go back to the Leisegen youth hostel, taking the Golden Pass route starting with a narrow-gauge train to Interlocken Ost. Like the Glacier Pass train, this one also used a rack railway on the steepest parts. I asked the conductor how steep those parts were, and she said they were 5 percent. Only one major rail line in America has a 5-percent grade; normally 2 percent is the steepest they go.

At Interlocken Ost I made an across-the-platform transfer to a double-decker Swiss train. I knew I would have to get off this train at Interlocken West, but in the five minutes I was aboard, I fell in love. If Amtrak Superliners had been like these cars, I would still be riding Amtrak. The outside of each car had a lighted sign saying where it was going, what time it would arrive at the next stop, and what was inside the car.

While Superliners are all nearly identical (okay, four kinds: coaches, sleepers, dining, and lounge), each car on this train had its own purpose. One was a kids' car with toys and a playground. One was a quiet car where talking was forbidden. The diner had a fantastic menu. The ride was quiet and the interiors were broken up into lots of intimate compartments. I want to go back to Switzerland to bicycle and ride more scenic trains, but mainly I want to take a longer trip on this double-decker train.

After riding eight trains in one day, I arrived at Interlocken West too late to take the last train to Leisegen. Fortunately (because I was out of Swiss Franks), my Eurailpass got me aboard a bus and I enjoyed both dinner and next-morning's breakfast at the youth hostel on the Thuner See.

The next morning I caught a train to Spiez where I took a Golden Pass train to Zweisimmen. This was painted a bit differently from other standard-gauge Swiss trains but otherwise was not particularly special. However, the narrow-gauge train from Zweisimmen to Montreux was very unusual.

The engineer sat in a compartment above the passengers in the first car, which had a huge glass window in front. (The actual engine powering the train was in the middle of the train, a not-uncommon Swiss practice.) The window gave a few passengers an engineer's-eye-view of the scenery. I had inquired about getting a reservation in this car and was told it would cost 5 Franks (about $4), but that no space was available the day I wanted to go.

Yet when I got aboard, there was no one in the front compartment. So I moved in and when the conductor came to collect tickets I offered to pay the extra 5 Franks. Probably because it was raining, he said "it's okay." Despite the rain, I ended up taking more video from this seat than during the entire rest of the trip combined.

In the U.S., one of the arguments against urban sprawl is that farmers could not possibly do their work if surrounded by homes and other urban developments. Yet throughout the French and Italian portions of Switzerland I saw vineyards and other farms mixed in with residential areas.

This train ended at Montreux on Lake Leman (or, as one Swiss passenger told me, "You would call it Lake Geneva"). I consulted schedules and realized I would have three hours to divide between Montreux, Laussane, and Geneva. I spent an hour in Montreux, took a train to Laussane where I spent 40 minutes, then a train to Geneva which I wandered around for about two hours. From Geneva I took a French TGV back to Paris.

Despite not having any Internet connection during my entire time in Switzerland, I managed (using a Swiss Telecom pay phone) to get an email to Vickie to get an email to Wendell letting him know when my train would arrive. The message got through and he was waiting for me at the station, which was fortunate because I probably would have gotten lost trying to find his apartment.

Wendell had rented a car for us, and the next morning we were off through Belgium and the Netherlands to Leipzig, Germany where we would look at the suburbanization of the former East Germany. Along the way, we stopped to take videos of TGVs at speed and to see the site of the battle of Waterloo.

Near Waterloo was the town of Tervuren, namesake of the breed of dogs that own Vickie and I. So naturally I had to see it. We saw some nice streetcars, but no Belgian sheepdogs.

Germany is famous for its no-speed-limit Autobahns. When we picked up the rental car, the agent asked if we wanted to spend $270 more to get a BMW. I said no, but Wendell was disappointed that our Opel could go only 204 kph, or about 125 mph. Wendell later observed that it took me a few miles to get adjusted to going much faster than 140 kph (90 mph), but soon I was comfortable at 160 (100 mph) and even got up to 200 on one brief occasion.

The Autobahns aren't entirely without speed limits, of course. A lot were under construction, and construction speeds were about 80 kph. Speeds in congested areas such as urban areas and steep grades ranged from 90 to 130 kph. But we always appreciated seeing the sign that had a red slash through the speed limit. On French freeways this would mean 130 kph, and Wendell said he knew of an Italian freeway posted for 150 kph, which he thought was the fasted posted limit in the world. But in Germany it meant no limit. I could feel Wendell's pain when we drove at a mere 190 kph and were passed by Audis, BMWs, and Mercedes like we were standing still.

Sometimes we were standing still, largely due to construction as Germany rebuilds the east German autobahns. Also, trucks did have strict speed limits, usually around 80 to 110 kph. These speed limits sometimes varied by commodity or type of truck; many trucks had their speed limits marked on the back. The result was that the right lanes of four-lane roads often seemed dedicated to trucks while the left lanes were used mainly by cars.

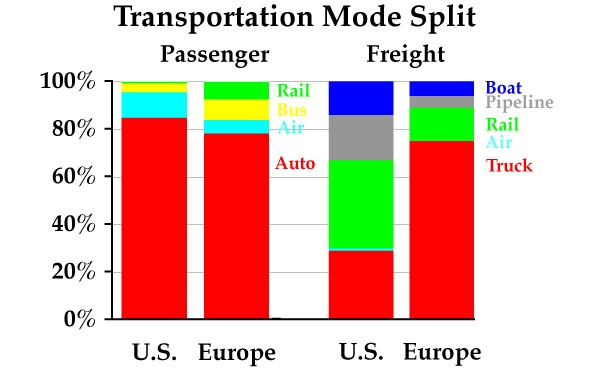

It is worth noting that Europe's heavy investments in passenger rail haven't taken many cars off the road, but they have added many trucks to the region's highways. Less than about 1 percent of U.S. passenger travel is by rail, compared with 6 percent (and declining) in Europe. But 75 percent of European freight movement is by highway, compared with 29 percent in the U.S. Just think: If the U.S. spent hundreds of billions on passenger rail, as Europe has done, we might take 5 percent of cars off the highway, but more than double the number of trucks.

On the route to Leipzip we paid homage to the world's oldest monorail, in Wuppertal, Germany. It opened in 1901 and currently carries about 70,000 people a day at a top speed of about 35 mph along its 8-mile route. The people of Wuppertal love their monorail so much that thousands of them drove downtown to watch it go by, or at least that's what Wendell must have thought as he sat in traffic going around the block while I took my videos.

Leipzig is not the biggest city in Germany, but the next day we found that it has one of the biggest train stations in the world. Someone later told me this was because Leipzig used to be the home of many international trade shows. The station had two entry halls, each of which would rival almost any big-city train station in America, connected by a massive terminal that had been unobtrusively converted into a three-level shopping mall.

The terminal opened onto a train shed that housed more than two dozen tracks, plus several more tracks for commuter trains that didn't quite make it into the shed.

After watching an endless procession of trains enter and leave the station, we drove out to a major shopping mall that had recently opened in Leipzig. The mall included a giant home-and-garden center, Woolworths, a hypermart, and all sorts of smaller stores, anchored by two large parking garages along with a parking lot.

From the mall we ventured a little further out to the suburbs and found lots of mostly new single-family homes. These contrasted sharply with the high-rise apartments built during the East German era.

Halle-Neustadt was a new town built exclusively of such apartments, making it the worst hell I encountered in Europe. Since German reunification, it has been deserted by more than a third of its residents, and dozens of buildings are being torn down. My visit to that city is described in more detail in my article on Smart Growth and the Ideal City. The word halle means "salt" in Greek, as there used to be a saltworks in the now-industrial city.

From Halle-Neustadt we drove to Berlin, which we explored the next day. Berlin has a huge new office-and-shopping area located a little ways away from its historic center. We drove past this complex along with many older buildings.

As we were leaving Berlin, we stopped at the Olympic Stadium, home of the 1936 Olympics where Jesse Owens won a gold medal. A street near the stadium is named after Owens. Nearby I found Corbusier House, a prototype high-rise apartment building designed by the famous modern architect and infamous city planner, Le Corbusier.

On the outskirts of Berlin, we found several model homes on display by local homebuilders. One of them told us they had a method of prefabricating walls that allowed three people to put up the entire basic structure in one day. Construction of the complete home required three months. The builder said they sold mainly to people who already owned a lot; few builders were able to buy enough land to make an American-style subdivision. This meant that, even with prefabrication, costs were considerably higher than in the U.S. This particular builder's homes cost about $190 a square foot (though admittedly this seems high partly because of the current weakness of the dollar).

From Berlin we drove to Dresden, which had been fire-bombed in World War II. Some of the city's more beautiful historic buildings were reconstructed almost from scratch. As near as I can tell, for example, the black stones are the only parts of this church that are original.

Throughout Germany, we passed many villages in valleys and on hillsides. On our way to Stuttgart, I suggested we stop at one. The village of Forst had an old church and some old houses crowded together, but many more newer homes built on American-sized house lots. Though we saw a passenger train go by in the distance, there was no station and most employed people who lived in Forst obviously had to drive somewhere else to their jobs.

After spending the night in Stuttgart, we drove to the French border. European highways are marked with signs with pictures of some of the historic buildings and other sights accessible from upcoming exits. Most of the pictures were meaningless to me, but after we entered France I saw one that was unmistakably Ronchamps, another building by Le Corbusier. Unlike most of Corbusier's blockish buildings, this church was designed with lots of curves. So we drove out of our way a few kilometers to see it.

That night we reached Avignon, "the home of the popes," because for a few years in the late fourteenth century, chaos in Rome forced some of the popes to make their home here. The head of the department in the Paris school where Wendell teaches has a second home in Avignon, so we had dinner with him and a couple of his daughters.

His ten-year-old daughter, Laura, knew some English, so I showed her photos of my dogs. Her eyes lit up when I mentioned their names, Chip and Buffy. "Is that like Buffy the Vampire Slayer?" she asked. When I admitted we had named our dog after a television character, she proudly stated that she had all the Buffy DVDs. While she showed me her photo of the show's star on her cell phone, I let her listen to some Buffy music on my iPod, and she said she had watched the episode with that music just that day.

The next day we drove to Paris but had several more sights to see along the way. First was the Pont du Gard, the largest remaining remnant of a Roman aqueduct. It is about 150-feet high and 900-feet long.

I hiked along the route of the aqueduct to get some photos from above.

Then, near Millau, we wanted to see the new Viaduc du Millau, a 1.5-mile long bridge that opened earlier this year. At 1,200-feet tall at its highest point, this is the tallest bridge in the world. Built by a private company, its cost of about $400 million should be covered entirely by tolls.

We drove around awhile trying to find places where we could photograph the entire bridge. Eventually we came to an enchanting town called Peyre built on a hillside, almost like an Anasazi cliff dwelling. Wendell and I parked in a cave under the cliff and walked the narrow streets through the town, taking photos that sometimes included the Millau bridge in the background.

We still had a few hundred more kilometers before Paris, but the bridge and town of Peyre proved to be a fitting climax to my European trip. Someday I hope to bicycle and ride more trains in Switzerland, and maybe even go back to Peyre.