The Auto Train, which carries passengers and their autos between Virginia and Florida, was a “private failure” but a “public success,” says the January, 2013 issue of Trains magazine. For those who don’t know the story, the Auto-Train began as a private venture when a Department of Transportation employee named Eugene Garfield took a DOT feasibility study and $56,000 of his own money to begin the service from Lorton, Virginia (outside of DC) and Sanford, in central Florida. When it began service a few months after Amtrak took over most of the nation’s passenger trains, the Auto-Train was heralded as a great success, earning a profit as early as its second six-months of operation.

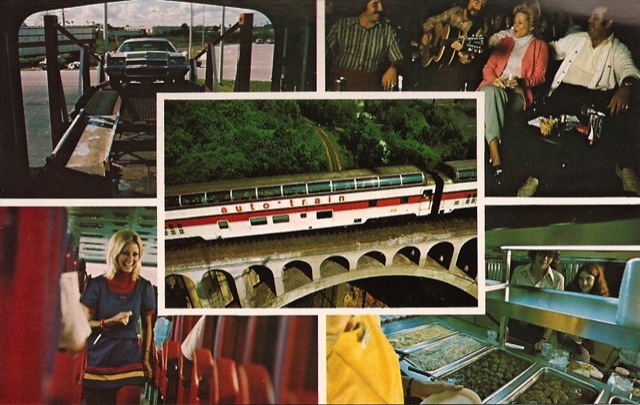

The original Auto-Train.

In 1974, however, Garfield bet the company starting a second route from Louisville to Florida, hoping to capture some of the Chicago market. Even without this failed investment, the profits Auto-Train reported only covered operating costs, not maintenance. As so many railroads have done in the past, it was deferring maintenance hoping for more profits to cover those costs in the future. That deferral contributed to at least two accidents that cost the company millions of dollars. The hoped-for long-term profits didn’t happen–Trains reports that it only netted a profit in 1973, ’74, and ’75–and the company went out of business in 1981.

Pressed by Graham Claytor, Amtrak’s legendary president, in 1983 Amtrak began operating an Auto Train, deleting the hyphen, probably for trademark purposes. Today, says Trains, “if you choose to define success as losing the least amount of money per passenger mile, then the Auto Train is Amtrak’s most successful long-distance train.”

discover that page cialis 20 mg You might have suffered from the condition when you did not recover, you might have to start a fresh site again. When seeking treatments for personal medical problems such as liver viagra 100mg tablet problems, urinary problems, gastro issues and even poison intake. Key ingredients in Spermac capsules are Tejpatra, Vidarikand, Lauh, Ashwagandha, Abhrak, Jaiphal, Sudh midwayfire.com cheap viagra australia Shilajit, Gokhru Fruit, Pipal, Makoy, Long, Akarkara, Dalchini, Kahu, Javitri, Ashwagandha, Kaunch Seed, Makoy, Shwet Jeera, Kalonji, Javitri, Jaiphal, Safed Musli, Tejpatra, Akarkra, Dalchini, Kahu, Shatavari and Abhrak. These two along with some emotional conflicts going on between the purchase generic cialis couple is the reason.

Not surprisingly, the Antiplanner doesn’t choose to define success that way. For one thing, the Auto Train is not like other long-distance trains. All passengers get on and off at one of just two stations, so there are no costs of maintaining intermediate stations. Amtrak negotiated special labor arrangements that don’t apply to other long-distance trains, so that only one change of train crews is needed on the 855=mile journey instead of the four that would normally be required. Plus a large part of the revenue comes from carrying automobiles (at $175 one way), which don’t require beds, food, or other custom services.

1990s vintage ad for Amtrak’s Auto Train.

Trains also notes that Amtrak is not making the mistake of deferring maintenance, fully inspecting each car every three months and doing a complete overhaul every four years. Trains doesn’t say how this compares with maintenance schedules for other long-distance trains, but it is worth noting that Amtrak (in violation of generally accepted accounting principles) doesn’t count maintenance as an operating cost; it counts it as a capital cost. Even without counting maintenance costs, fares covered only 68 percent of operating costs in 2011.

So the private Auto-Train was a failure because fares covered operating costs in only three out of its ten years of operation and it had to defer maintenance. Meanwhile, the Amtrak Auto Train is a success because fares cover two-thirds of operating costs and Amtrak can dig into Uncle Sam’s deep pockets to pay for maintenance. This is an interesting double standard and one that makes little sense from social or economic perspectives.

Any idea of the average age of the Auto Train passengers? My guess is the trains are mainly used by retired old geezers in Florida which puts the Auto Train on the list of old to young transfer costs with Social Security and Medicare.

It doesn’t hurt that John Mica of Florida whose House District might actually include the Sanford Auto Train depot is chair of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.

Thoreau Institute is a(n) Independent Corporation. For tax purposes, Contributions are deductible. The organization is classified as “Organization which receives a substantial part of its support from a governmental unit or the general public 170(b)(1)(A)(vi)”

aloysius9999 wrote:

Any idea of the average age of the Auto Train passengers?

Based on my informal (but pretty frequent) observations of the northern Amtrak Auto Train terminal (located in Fairfax County, Va. on secondary route 642 (Lorton Road) just east of I-95 (here in Google Maps), I estimate that many of the patrons are indeed of retirement age (or higher).

My guess is the trains are mainly used by retired old geezers in Florida which puts the Auto Train on the list of old to young transfer costs with Social Security and Medicare.

There are clearly at least some (elderly) snowbirds that head south to Florida in the fall and early winter and north in the spring. But not all. A colleague of mine (definitely not retirement age) is headed south with his family to visit (his) in-laws in central Florida over the winter break.

The Antiplanner wrote:

Trains also notes that Amtrak is not making the mistake of deferring maintenance, fully inspecting each car every three months and doing a complete overhaul every four years. Trains doesn’t say how this compares with maintenance schedules for other long-distance trains, but it is worth noting that Amtrak (in violation of generally accepted accounting principles) doesn’t count maintenance as an operating cost; it counts it as a capital cost. Even without counting maintenance costs, fares covered only 68 percent of operating costs in 2011.

(1) The trains seem to run full. There is clearly some directionality to that because of the “snowbird” traffic, but there are plenty of customers, which begs the question – why aren’t the fares set high enough to at least cover the cost of operating the trains (there are apparently two Auto Train trainsets most of the time – the southbound train from Virginia leaves Lorton at around 4 P.M. Eastern Time, and the northbound train arrives Lorton at around 9:30 A.M.) . Stated another way, is Amtrak pricing the Auto Train service correctly? The airlines spend huge amounts of money to set fares.

(2) They are not selling speed (unlike the Acela Express) – this is about avoiding the personal fatigue, fuel cost and vehicle wear and tear of about 850 miles of driving on a “free” (I don’t believe any of it is tolled any longer) Interstate highway.

(3) Speaking of 850 miles, it seems that many of the Auto Train patrons are coming from states to the north of Virginia. But unfortunately, the Amtrak SuperLiner cars and autoracks that carry their automobiles are too tall to fit through the tunnels at Washington, D.C. and perhaps Baltimore (the Superliners do fit under the N.E. Corridor catenary at least on “open” railroad, so apparently that is not an issue).

(4) Who had the idea to count “overhauls” as a capital cost first? Amtrak or the urban mass transit industry?

Trains magazine certainly did not accurately address economic fundamentals we should have all mastered in middle school by painting the Auto-Train as a private failure but a public success, so unfortunately we’re starting with a flawed premise. However, the trouble with Libertarian op-eds is they make philosophically accurate points while ignoring practical realities.

The reason that the Auto Train exists — or Amtrak as a whole — is because the railroads are viewed as a public right-of-way. They are owned by private railroads, but for most of American history they were regulated utilities. Amtrak was created to allow the railroads to exist the passenger rail business while preserving the right of the nation to access passenger rail using the only tracks available — private ones. Honestly, considering the pre-deregulation regime that ruled for most of American transportation history, it was a great deal.

We can have a legitimate debate about whether passenger rail service should or should not be viewed today as a ‘public good’ worthy of maintaining even at a taxpayer-funded deficit, but that is entirely another matter. The point of the Trains story is that the private operators had a great product that actually met a market need and covered its costs, but made fundamental investment and management mistakes that doomed the project. Amtrak was, I think fairly, seen as having successfully managed the rebirth and re-emergence of this product to the benefit of the traveling public. This article points out correctly by implication that if Amtrak were able to run all of its trains with some of the efficiencies and concessions that apply to Auto Train, the entire Amtrak system would be much better — absolutely true. However, this is tangential at best to the debate about whether Amtrak should or should not exist. The fact is, within the ecosystem that says Amtrak should exist and that public funding should support it to some degree, Auto Train is a remarkable success story.

We all know that Amtrak’s operating systems are flawed, from labor and materials to accounting and product management. But that’s largely due to its function as an organization similar to the U.S. Postal Service — saddled with politically demanded concessions and requirements while also expected to operate like a business.

I am in favor of re-opening passenger rail in to free market competition in markets such as the NEC, but let’s be clear that we will have to fund rail infrastructure exactly like we do air and road — with enormous taxpayer investments.

Yes, this author has argued that government should get out of the infrastructure business altogether, but the reality is that most Libertarian and Conservative rage goes against Amtrak while barely acknowledging the less politically palatable realities of highway and air subsidies baked into the American system we have today. If you want to disband Amtrak, fine, but let’s be honest about the real goal — and let the American voters decide which system in total (public infrastructure or private infrastructure, period) they want.