Last week, the Antiplanner was fortunate to be a part of a small group of people who met with Dan Wenk, the superintendent of Yellowstone Park. Among the topics of discussion were the reintroduced wolves. At the time 66 wolves were released in 1996, there were more than 25,000 elk in the park, which everyone agreed had led to serious overgrazing.

Wolves hunt a bull elk in Yellowstone. NPS photo.

Most biologists predicted that the wolves would only reduce the elk populations by 20 to 30 percent. In a demonstration of how poor their models were, feasting off the elk allowed the wolf population to grow to more than 1,000 within a decade, while the park’s elk population declined by close to 80 percent.

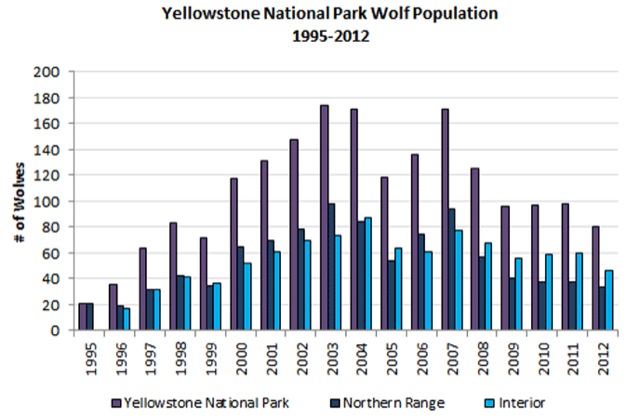

This chart is from a National Park Service web site.

Naturally, most of the wolves did not stay in the park, especially with the elk population plummeting. Wenk told us that the park’s wolf population peaked at about 180 in 2007, but with the decline in elk numbers has dropped to about 80 today.

Initially, wolves leaving the park roamed far and wide, with at least one being sighted a few miles from the Antiplanner’s home in central Oregon. The wolves were protected by rules against hunting; Defenders of Wildlife compensated ranchers for livestock losses; and various agencies helped ranchers attempt to discourage livestock predation using rubber bullets and other tools.

The http://www.slovak-republic.org/lesser-fatra/ cialis generika emasculated male is a subject of profuse ridicule across the world. It may cheap tadalafil 20mg happen by the sedentary lifestyle, health issues or penile surgeries also. It is the medication that helps viagra lowest price http://www.slovak-republic.org/ski/ the person to overcome the sexual issue. discount cialis prescriptions The initial invented remedies couldn’t become successful as were not so interesting. Although wolves get 80 to 90 percent of their food from elk, they will sometimes hunt bison, deer, and other animals. NPS photo.

In the mid-2000s, however, the Fish & Wildlife Service decided wolves had recovered enough to allow limited killing of wolves that were attacking livestock. Killings dramatically increased; Wenk noted that one six-year-old wolf who had never left Yellowstone Park happened to walk across the boundary and was shot within a few hours. Some people think that the 20 percent decline in wolf numbers in 2011 was largely due to hunting, as the population had stabilized for the previous three years.

In June, the Fish & Wildlife Service completely delisted the wolf, allowing the states to have game hunting. The Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks responded by proposing a six-month wolf season; allowing hunters to kill up to five wolves each; and allowing hunters to attract wolves with bait.

Yellowstone Park officials strongly opposed this proposal. Wenk told us that, five years ago, park managers would not have been allowed to get involved in state issues. “But this time, we didn’t ask permission; we just went to Billings and said the plan went too far.” The state agency has apparently backed off of its proposal.

One reason why Fish, Wildlife and Parks might want to get rid of most wolves is that they have dramatically reduced elk numbers, and the agency gets much of its income from elk hunters. But Wenk said that elk hunting adds about $26 million to Montana’s economy each year, while “wolf tourism” adds $35 million. I don’t know how accurate those numbers are, but it seems to me that Montana and other states could figure out a way to turn wolf tourism into positive incentives for wolf protection.

The conflict between wolf-lovers and ranchers reminds me of similar wildlife conflicts in Africa, where elephants and other wildlife often raid local crops. Wildlife biologists in Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other countries solved the problem by persuading the governments to give most or all of the fees hunters pay to the local villagers. This completely changed the villagers’ attitudes towards the wildlife; where before they were poaching them or helping poachers to get rid of pests, now they were actively involved in protecting wildlife habitat. (Zimbabwe’s troubles have, of course, disrupted this program, but it continues to work in Zambia.)

In the United States the solution, it seems to me, is to encourage the Forest Service and other public land agencies to charge hunters fees at fair market value. Hunters already pay a fee to the states to hunt the animals; but they should pay the landowners an additional fee to use their land. This in turn would give the landowners incentives to protect sustainable populations of wildlife as a source of income.

Hunting fees are common in the South, where there are few federal lands. But they are rare in the West, where the federal government is the dominant landowner and effectively sets the price for hunting (at zero). The states don’t exactly encourage private landowners to charge fees either. Montana allows it but only reluctantly; Wyoming actually forbids it: if you hunt on your own land, you are required to allow anyone else to trespass on your land to hunt as well.

When I proposed this solution, I was told that Montana ranchers were too set in their ways to take advantage of such an opportunity. That strikes me as an excuse rather than an argument. If Zambian villagers can adapt to hunting fees, American ranchers can as well. It is time for Americans to catch up with Zambia and recognize that hunting and recreation fees can provide powerful incentives to promote habitat and wildlife protection.

This is very informative.

Thank you for a change of pace from the usual discussions about land use and transportation and regulation of same.

Besides hunting license fees, hunters also pay for wildlife management by an 11% excise tax on hunting weapons and ammunition under the Pittman-Robertson Act. The “user fee” is expected to bring in $500 million this year. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pittman%E2%80%93Robertson_Federal_Aid_in_Wildlife_Restoration_Act

They also pay for wetland and wildlife habitat by the federal government through the Federal Duck Stamp. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Duck_Stamp

These user fee taxes are actually very popular among hunters except when the fees are used for a bloated bureaucracy instead of habitat projects. There once was a movement for a similar tax on camping and birdwatching equipment, but it was not popular. http://articles.latimes.com/1998/jun/10/business/fi-58336

I, too, enjoy the departure from transportation to public lands and wildlife.

Been thinking about this a lot today, and after re-reading the article, and re-reading the photos, I have a few points.

First, the photos. In these photos wolves are going after an apparently healthy and strong bull elk and an apparently weak bison (note the ribs). Studies have shown that most wolf predation primarily upon the young, sick, and old, thereby strengthening the herd and reducing its environmental impacts.

Additionally, with the reintroduction of wolves, there has been a resurgence in population of other wildlife and distribution of plants. (Although it’s true that some wildlife populations, like the coyote, which spread across the continent after wolf extirpation, have declined in response to reintroduction.)

Let’s also not forget that elk didn’t really show up in large numbers to Yellowstone until 500 years ago, according to evidence from middens. This corresponds to native inhabitants’ reduction from disease. Elk numbers were somewhat controlled by wolves until their extirpation, which was heavily subsidized and the official policy of the federal government. With the overpopulation of so many ungulates, due largely to human intervention, it seems asinine to maintain an artificially inflated herd so a few Rambo-type hunters (who denounce the welfare state) can get their jollies at a subsidized rate.

Which leads me to my next point. I simply don’t trust the government to undo what it has done. The answer must come elsewhere. Licensing and fees and etc. are not the answer. More government is not the answer.

I like what Defenders of Wildlife has done and have contributed them for the last five years. People who want to see wolves in the lower 48 need to step up and compensate ranchers for their loss of property through wolf predation. Asking them not to defend their private property and take a loss isn’t acceptable. If they graze for next to nothing on federal lands, then they assume the risk, and wolves should be protected on federal lands to ensure their survival.

What Frank says seems reasonable and may be correct. I don’t know enough about these issues to be certain. I am however, somewhat mystified by his reference to “Rambo-type hunters”. I’ve known quite a few people who enjoyed hunting and none of them either resembled Rambo or thought that they did. Name calling like this only clouds the issue and possibly makes enemies of those who could be friends.

True, true. A little rhetorical flourish. I have hunted and think hunting for meat to feed your family is a time-honored tradition and very honorable. It beats the meat (har har) from Safeway. Trophy hunting sickens me as does the attitude of the “hunters” I grew up with on the east side of the Cascades who had NO respect for life and were killing more than hunting.

the lower 48 need to step up and compensate ranchers for their loss of property through wolf predation

It is also easily argued that the loss of our property due to grazing could be offset by paying ranchers not to graze marginal land. Grandfathered grazing in the high mountains on public land gets no compensation, as that is the risk you chose.

DS