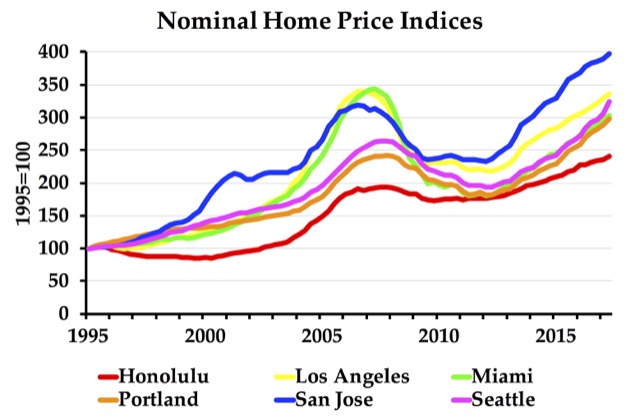

Zillow reports that “home values grew the most in markets with the strictest land-use regulations.” That’s not exactly news to Antiplanner readers, but it’s nice to hear others confirm it.

Unfortunately, Zillow bases its measure of who has strict land-use regulations on the Wharton Land-Use Regulation Index. This is the best index available but it still has a few problems. First, it is more than ten years old. Second, it only measures the strictness of city zoning, not the strictness of rural zoning near the cities (i.e., growth management). Third, it doesn’t measure how easy it is to get variances or zone changes.

As an example of the problems, Zillow concludes from the Wharton index that Houston and Dallas have “medium strict” regulations, while the least-strict rules are found in places such as Indianapolis and Kansas City. Of course, Houston has no zoning, though it does regulate heights and setbacks. The unincorporated areas around both Dallas and Houston also have no zoning and don’t regulate anything except development in riparian areas. Continue reading