The Antiplanner hasn’t finished reading Marc Levinson’s The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America, but the story he tells is essentially the same as that told by former A&P executive William Walsh in The Rise & Decline of the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, a book the Antiplanner discussed nearly three years ago. Despite the similarities, the two writers have very different slants, one essentially pro-capitalist and one subtly anti-capitalist.

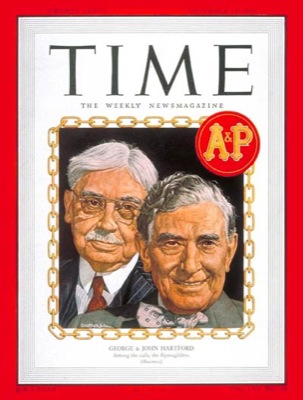

To Walsh, A&P is a classic American success story. Founded by George Hartford as a tea shop in Manhattan in 1859, the company was grown by his children, George and John, to more than 16,000 stores that dominated the grocery trade in much of the United States. The average store was small by today’s standards, selling only 400 to 500 different products. When the first supermarkets were developed in the 1930s, the Hartfords jumped on the bandwagon and quickly replaced their shops with a smaller number of much larger stores. Like WalMart today, A&P in the 1930s through the 1950s was considered an unstoppable juggernaut.