Most people know Henry David Thoreau as the guy who wrote a book about living in a shack by a pond. Some people remember he also gave a speech about why he refused to pay a tax levied by the federal government to support the Mexican-American War, which he regarded as immoral. These events occupied little more than one of Thoreau’s 44 years of life.

Few people know of Thoreau’s other accomplishments. Working as a civil engineer, he surveyed thousands of acres of land in rural Massachusetts. Given his avocation as a naturalist, he made a genuine contribution to the scientific literature of what we now call “ecology” by discovering the process of plant succession.

In sharpest contrast to our stereotype of Thoreau as an anti-materialist, Thoreau was an entrepreneur. He developed the methods and invented the techniques for making the finest pencils in America. He personally manufactured and marketed many of those pencils, winning awards for Thoreau pencils.

The Thoreau pencil company was actually started by Henry’s father and uncle when Henry was about 8 years old. In the early nineteenth century, pencils were far more important than they are in today’s era of the ubiquitous ballpoint pen, not to mention word processors and AutoCAD. But most American pencils, Thoreau’s included, were of poor quality: the lead tended to be greasy and to easily smear.

In 1838, after graduating from Harvard and finding other jobs uninteresting, Henry started work for his father’s pencil works. In addition to just helping make pencils, he embarked on a crash R&D program to improve the quality of his family’s pencils.

Pencil lead is made by combining graphite with a binder. As binders, American pencil makers used glue and various waxes. As Henry Petroski describes in his book, Pencil, Thoreau somehow rediscovered the idea of using clay as a binder. Though this process had previously been developed by a European in 1795, it was not actively used by most European pencil makers in 1838 and Petroski could find no evidence that Thoreau had access to any publications describing the process.

Clay had a double advantage over other binders. First, it solved the problem of greasy pencil marks. But Thoreau also discovered that, by adjusting the ratios of graphite and clay, he could make pencils that were harder or softer. Thus, the Thoreau Pencil company was the first American company to offer pencils in four different degrees of hardness. During much of the 1840s, Thoreau made the most highly prized pencils in North America, if not the world.

Some of the company’s pencils were labeled “J. Thoreau and Son.” Henry, of course, did not turn pencilmaking into his avocation. But for the rest of his life, Thoreau drifted in and out of the pencil business, helping his family to make pencils and improve their product whenever he or his family needed extra money.

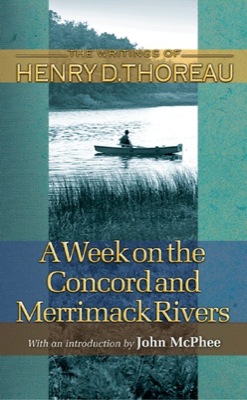

For example, in 1844 he returned to the pencil factory to help make enough pencils for his parents to buy a new home. In 1849, he made a special batch of several thousand pencils to help finance publication of his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.

One of Henry’s innovations was the design and construction of a giant plumbago grinder (plumbago was a nineteenth-century term for graphite). The finer he could grind the graphite, the better the pencil lead.

Eventually, other pencil makers caught up with Thoreau’s methods and technology. In 1853, the family stopped making pencils and instead sold their graphite to printers for electrotyping. After Henry’s father died in 1859, he personally continued to manage this business until he died in 1862 at the age of 44.

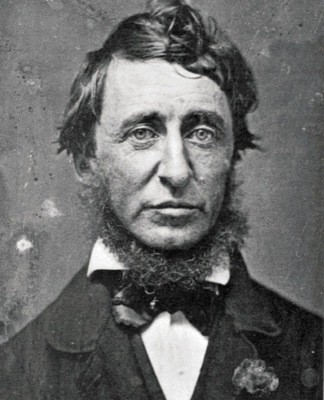

Photo courtesy of the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods.

Henry was not a great entrepreneur in the sense of Henry Ford or John D. Rockefeller — but then, there were few great entrepreneurs in early nineteenth-century America. Today, Thoreau is claimed by many who would like to deindustrialize the world in the name of environmental protection. This is a sad misreading of history.

While Henry supported the protection of natural areas, he expected private property owners to do such protection. John Muir, who admired Thoreau’s writings, nevertheless referred to Henry as “that huckleberry picker” because he would not have supported Muir’s program of using big government to protect wild areas.

Thoreau made it clear by both his actions and his writings that he would oppose such movements. Though known as a naturalist today, he often signed his name as a “civil engineer.” He objected to the “obstacles which legislators are continually putting in” the way of “trade and commerce.”

“If one were to judge these men wholly by the effects of their actions and not partly by their intentions,” he added, “they would deserve to be classed and punished with those mischievious persons who put obstructions on the railroads.” As such, Thoreau is an inspiration to those who believe environmental protection is compatible with entrepreneurship and business, and does not necessarily require big government bureaucracy and regulation.

While Henry supported the protection of natural areas, he expected private property owners to do such protection

Silly Henry David.

It’s nice to see a link to the real Thoreau Institute, the one in MA.

I still find it sad ROT uses Thoreau’s name in vain.