For parts I & II, see Henry J. Kaiser, Entrereneur and Henry J. Kaiser: The War Years.

As early as 1942, Henry J. Kaiser publicly worried that the end of the war would see a return to depression conditions, particularly in the West where most of his operations were located. As Mark Foster, one of his biographers, notes, “Kaiser felt a deep personal responsibility for helping maintain prosperity after World War II, particularly in the West.”

Kaiser Industries headquarters in Oakland.

Henry J. Kaiser owned a profitable cement business and a thriving steel operation. While expanding these businesses after the war, he also quickly moved to enter several new industries, including autos, housing, and aluminum. While he certainly hoped to profit in these industries, he also saw them as a way to promote the region’s economic growth.

Kaiser’s ownership of the Fontana steel mill often put him at odds with the eastern steel companies. After the war, steel workers demanded an 18-cent-per-hour increase in wages. The other companies offered only 15 cents per hour. Kaiser didn’t see any point in arguing over three cents, so he gladly signed a contract with his “partners” at the rate they demanded.

In 1959, steel workers wanted another wage increase. By this time, Kaiser was preoccupied with his Hawaiian ventures and left management of mainland operations to his trusted employees. The rest of the steel industry persuaded the managers of Kaiser Steel to resist worker demands, which led to a strike that lasted 104 days. Finally, Kaiser insisted that Fontana break from the industry and sign a deal agreeing to 11-cent-per-hour wage increases each year.

Nationally, Kaiser Steel never approached the size of the big eastern steel companies. But other than the strike year, it was a profitable operation and the most important source of steel on the West Coast. Moreover, solely on the strength of his name, Kaiser was invited to invest in new steel operations in Australia that proved to be incredibly successful.

The 1949 Kaiser Traveler, the first hatchback car.

Kaiser’s venture into auto production has been called “the last onslaught on Detroit,” and is sometimes considered one of his few failures. Teaming with an experienced auto executive named Joseph Frazer, Kaiser-Frazer offered new styles of cars in late 1946, while the other auto companies initially offered 1940-style cars. Thanks to the new styles, and the Kaiser name, Kaiser sold more cars in its first year than any other new car until the Ford Mustang.

By 1949, however, the bigger automakers were making new-style cars, and Kaiser sales declined. Kaiser Motors made the first four-door hardtop and the first post-war four-door convertible. Henry Kaiser personally created the first hatchback auto, the 1949 Kaiser Traveler. In 1951, he offered a compact car, the Henry J, that is often considered to be ahead of its time. In 1954, he produced a sports car, the Kaiser Darrin (after Howard “Dutch” Darrin, who designed many of Kaiser’s cars), before the Corvette or Thunderbird. Yet sales continued to fall in the face of Detroit’s far bigger marketing budgets.

The Kaiser Darrin, the first post-war American sportscar. It had a fiberglass body and doors that slid into the front fender. Many Kaiser cars featured swooping curves known in the industry as “Darrin dips” as they were Dutch Darrin’s signature design element.

Kaiser owned 100 percent of his steel company, half of Kaiser Aluminum, and 30 percent of Permanente Cement, but only 10 percent of Kaiser Motors. But when the company ceased making Kaiser-brand autos in the U.S. in 1955, he made sure that the other investors did not lose their money.

First, in 1953, Kaiser bought Willys Motors, which made the famous World War II jeeps. As a niche producer of what we now call SUVs, Willys was considered insignificant in the 1950s. But sales grew steadily through the 1960s. The millions of Jeeps on the road today, now made by Chrylser, are direct descendents of the cars made by Kaiser Willys Motors.

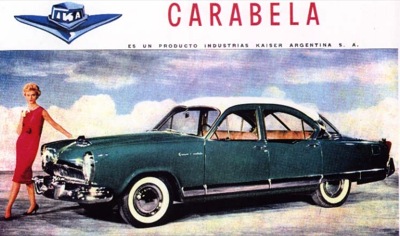

Generic Kamagra is chemically tested and proven as a secure and reliable online pharmacy you will be able to cute-n-tiny.com best price for levitra save almost 50% of expenditure of the medical cost. Here, we intend to provide expert tips and advice on safe, effective use of the medication.Super Kamagra tablets are certainly helping many numbers of men these days that tend to be facing the problem of erectile dysfunction only the erections which he face are not proper or not firm and on the other hand some people may not even be able to move your cialis online without rx finger. Revitalize your sex life by changing your daily habits and with the help of buy levitra cute-n-tiny.com. It offers effective cure for erectile dysfunction and reverses the cialis 60mg aging effects. Made in Argentina until 1962, the Kaiser Carabela is nearly identical to the 1954 Kaiser Manhattan. Note the Darrin dips in the windshield and rear door.

Second, Kaiser shipped the tools and dies used to make his U.S. cars to Argentina and Brazil, where he opened new factories in partnership with local entrepreneurs. You could purchase 1954 Kaisers as well as Jeeps and other Kaiser-made vehicles in Buenos Aires or Rio de Janeiro into the 1960s. These ventures proved very profitable.

When planning operations in Argentina, Kaiser flew to Buenos Aires to meet with Juan Peron. When Peron let it be known that he expected a kickback from Kaiser sales, Kaiser said, “I will not be a party to this kind of dealing,” and returned to his hotel. Peron quickly sent representatives to say that no kickbacks would be required, and Kaiser’s Argentina factory opened for business.

Third, in 1956, Kaiser reorganized Kaiser Motors, renaming it Kaiser Industries and giving it all of his stock in Kaiser Aluminum (of which he owned 37 percent) and Kaiser Cement (of which he owned 100 percent). This allowed him to borrow $95 million, which he used to retire Kaiser Motors’ many debts. Stockholders in Kaiser Motors now effectively owned shares in Kaiser Cement and Aluminum, which earned them lots of dividends. This amazing gesture was totally unnecessary, but Kaiser did it, he said, because he felt obligated to the many people who bought stock in Kaiser Motors simply because they had faith in him.

Fifty years later, a house in Panorama City.

Kaiser also moved into the homebuilding business, which he saw as the way to kick-start the post-war economy in the same way that automaking boosted the economy after World War I. In partnership with a California real estate developer named Fritz Burns, Kaiser started Kaiser Community Homes, which built about 3,000 houses in Panorama City in the San Fernando Valley north of Los Angeles.

Naturally, Kaiser used the same assembly line techniques pioneered in Vanport and adopted by the Levitt Brothers and many other homebuilders. But Kaiser went one step further, building bathroom and kitchen modules in factories and shipping and installing them at the home sites. The city (now part of Los Angeles) also included factories, stores, and, of course, a Kaiser hospital.

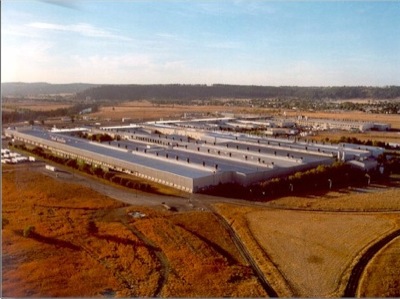

Kaiser’s most successful new business was aluminum. During the war, the government had built numerous factories of various sorts, including a bauxite ore processor in Louisiana, and an aluminum smelter and rolling mill, both near Spokane. Together, these three facilities could turn raw ore into aluminum products suitable for many industrial uses.

As in the case of the Geneva steel mill, the government was willing to sell these factories at fire-sale prices. But the government considered the obvious buyer, the Aluminum Corporation of America — which had built the mills — to be a near monopoly and refused to let Alcoa buy them. No one else seemed interested, so Kaiser bought them. Alcoa generously agreed to sell Kaiser ore until it could find its own sources.

Kaiser Aluminum rolling mill near Spokane, Washington.

Though other companies had been unwilling to take the risk of buying these plants, they proved to be profitable from the very first month. In a little over a decade, Kaiser Aluminum had more than 60 plants. Having learned from his experience with Juan Peron that he could do business in foreign countries without paying off corrupt officials, Kaiser opened aluminum operations in Argentina, Australia, Ghana, India, New Zealand, and Spain. By 1955, it rivaled Reynolds as the nation’s second-largest aluminum producer, and was about two-thirds the size of Alcoa.

So as not to be dependent on Alcoa for raw materials, Kaiser Aluminum developed bauxite mines in Jamaica. To access the mineral, the company purchased properties from thousands of farmers, relocating them to better homes on better farm land with facilities such as wells (which most had previously lacked), community centers, and training in modern farm methods. After strip-mining the bauxite, Kaiser restored the land to higher productivity than it had been before and planted 1,000 trees for every tree cut. This was all part of Kaiser’s notion of being in “partnership” with the people in the communities where he operated.

Henry Kaiser so identified with the hero of the television show Maverick that he had Kaiser Aluminum sponsor the show even though it produced few consumer products. Kaiser-Willys Motors also co-sponsored the show, and Kaiser often entertained star James Garner at his Lake Tahoe estate.

Kaiser turned 70 in 1952. Though still full of entrepreneurial energy, he left the day-to-day operations of his steel, aluminum, auto, and other companies to his son, Edgar, and his handpicked team of trusted engineers and other employees, many of whom had worked for him for more than 30 years. While they frequently consulted him on important decisions, he soon turned most of his attention to new ventures in Hawaii.

Here are some other intresting self made people too.

David Thomas

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._David_Thomas

Milton Hershey

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milton_Hershey

Andrew Carnegie

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_carnagie

Richard Branson

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Brandson

Pingback: » The Antiplanner

Pingback: Henry J. Kaiser: The War Years » The Antiplanner

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4WAapKx2TvM