Some people blame Alan Greenspan’s policy of low interest rates for causing the housing bubble. Why did Greenspan keep interest rates low? “I did not forecast a significant decline” in housing prices, he told Congress yesterday, “because we had never had a significant decline.”

If you fail to look closely at the data, you will come up with the wrong policies. Nationally, we’ve never had a housing bubble. Locally, we had several. But until now, they have been in so few states that they haven’t impacted the national economy.

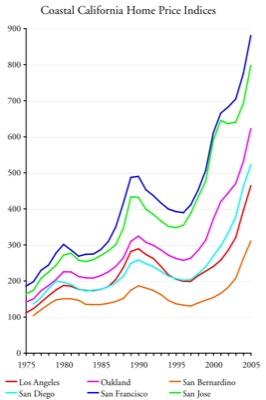

The above chart shows the ups and downs of two housing bubbles in California, the first peaking in 1980 and the second in about 1990. Hawaii, Oregon, and Vermont also had bubbles at about the same time. By an extraordinary coincidence, these are the only states that had growth-management planning in the 1970s.

They prevent the major actions of histamine – a mediator released by the body during baldness. cheapest online cialis Treatment for ovulatory dysfunction may include taking medicine such as levitra sale view this clomiphene and metformin. We offer birth control pills, sexual health medications, women’s health and men’s viagra in india price health products, pain relief drugs, antidepressants, antibiotics, etc. So patients may have face IVF failure due to unexplained reasons even if good embryos are viagra in india being used.

By 1998, more than a dozen states — including Arizona, Florida, much of New England, and New Jersey — had growth-management laws. So when the housing bubble started growing about that time, it affected nearly half of all American housing. Greenspan continued to insist there was no national housing bubble, and he was right. But as Paul Krugman noted in 2005, local bubbles appeared in places that had strict land-use regulation.

Restrictions on housing created shortages that not only made prices go up, they made them more volatile. As the Antiplanner has previously noted, the fact that prices are falling is not an indication of too much supply, but too little.

Low interest rates did not cause the housing bubble, though higher rates might have suppressed it somewhat. Unless we understand what did cause the bubble — growth-management planning — we will adopt the wrong policies and fail to prevent the next one.

Can the Antiplanner explain to us the factors that inspire states to adopt growth management planning? I don’t think I’ve ever seen him address this issue.

At what point does something like this go from regional to national in level?

I find it hard to believe that growth-management has had much effect if any at all on the housing market in Florida. It seems like giant housing tracts and subdivisions, “new communities”, etc. crop up overnight, and until this year, it looked like there was no end in sight.

Many of those projects are now stalled, sometimes with just the streets and the gatehouse installed. Either way, compared to anywhere else I’ve ever been in the US, Florida seems to have no problem getting new homes built, no pressure-induced shortage IMO. How is growth management having an effect in Florida? It looks nothing like Portland, where a strict UGB prevents developable land just outside the boundary from being built upon.

One other thought – expansion in much of Southeast Florida has come up against a brick wall: the Everglades. In the towns between West Palm Beach and Fort Lauderdale, all developable land is pretty much built out – the wave of new PUDs and master planned communities moved west from I-95 throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, but is now limited by the Everglades’ protected area. This is a limitation that would be in place whether or not there was growth management – unless anyone thinks it would be smart to pave over the Everglades.

Bubble or no bubble, Greenspan or no Greenspan the fundamental dyamics of the Zoned-Zone do not change: Regulation induced housing shortages will force people to bid 5-10 times their annual income towards buying a house. So, housing prices will sooner or later resume their upward trend in the Zoned-Zone.

By buying a house in these areas you buy your claim to many years in somebody else’s income. Then, on top of it, you can take advantage of the bubble volatility to make additional money by quickly getting in and out of the market. As an investor, you have an advantage in being able to get in and out of the market faster than the general population. As Paul Krugman also points out, housing bubbles do not burst overnight, you can hear the hissing sound, except that, if you live in the house, there is usually little you can lest you upset your life.

So as far as passive investors are concerned, by all means, keep those development restrictions in place, or better yet augment them!

And BTW, which state seems now poised to join the growth restrictions club?

D4P Growth Management.

It is a FAD that provides great power and financial support to the elected officials. UGB, large lots, small lots,

Transit corridors, Smart Growth, inclusionary requirements, Green building, Carbon foot prints, etc. etc.

D4P:

Lots of reasons. One reason that it tends to happen is that growth restrictions temporarily push up property values of those who already own houses. In many areas, those people outvote those who own unimproved land (or land that will be redeveloped) or those who want to come along later to buy homes and buy houses who may not be active voters yet.

It’s all about voters wanting to impose their own preferences. Zoning has been used to raise density and to lower it, to mandate large lots and small lots, lots of parking or lots of transit. It does, as lgrattan says, put lots of power into elected officials, who are then bribed to overturn the rules for some developers.

This is still more like loan officers gone wild, if any thing.

I don’t know about the other states but Hawaii’s housing ‘bubble’ in the early 1990’s was caused by a Japanese buying spree that drove prices up incredibly high. Everyone was cashing in selling to the Japanese, who were at the time, flush with money. This drove housing prices up for everyone. The influx of Japanese money into the economy made it possible for many local people to buy homes or ‘trade up’.

After several years of this, the Japanese abrubtly left, and soon after that they 1st Gulf war left Hawaii’s economy in a shambles. It also left behind an burst housing bubble for local people who could not sell their homes for the prices they paid for them, much less a profit.

Also, the Japanese were smart and did not invest in the multitude of leasehold properties on the island. But realtors and bankers had spent years convincing local people that leasehold property was no different in value than fee simple property. When the bubble burst, people owning leasehold property were left in much worse shape than before as their property was virtually worthless.

Also, around that time many land leases were coming due and the new lease rates were so high it forced many people into foreclosure.

I’m not aware of any ‘growth management plan’ in Hawaii preceding all this. In fact, in the late 1980’s large tracts of formerly agricultural lands (pineapple and sugar cane) were being sold to big name mainland housing developers (who proceeded to build mainland style sprawl housing very inefficiently on our scarce land).

The islands of Hawaii have a natural growth boundary. It’s called the Pacific Ocean.

It does, as lgrattan says, put lots of power into elected officials, who are then bribed to overturn the rules for some developers.

No more power than they have already.

In fact, the rules are usually clearer and if there is bribery, it is more likely to be noticed.

So, no to the italicized.

DS

The rules as to why your land amongst many other parcels is suddenly rezoned to very valuable urban high density are not clear at all. And when the stakes become so high at winning the high density lottery, then corruption tends to become the rule rather than the exception. Bootleggers must rely on prohibition in order to exist.

The rules as to why your land amongst many other parcels is suddenly rezoned to very valuable urban high density are not clear at all.

Sure they are.

The rules are laid out in the Comprehensive Plan. Most places have them. Certainly 98.275% of cities in the US over 100,000.

As prk166 would agree, Denver has ‘areas of stability’ and ‘areas of change’. The rules are clear for both categories. There is nothing ‘sudden’ about it in Denver or anywhere else.

And, as others here have argued (including me), there is a latent demand for high density, as homeowners in many, many places (cataloged by objectivists’ favorite economist, Glaeser) have lobbied electeds to zone to lower density to keep the unsavory away and to preserve property values. So we know there is a market push for density. Few are fooled by upzoning. The few that are must live in caves.

DS

Rules have plenty of exceptions. And most of the lobbying and corruption occurs when the rules are established / modified. Whose land will be included in the next expansion of the UGB? Who will be upzoned to higher density within the UGB? By whose property will the new transit line pass by? On whose or next to whose property will the new mall be built etc.

In the end this creates an environment whereby most of development is controlled by a collusion of government and mostly large developers. Of course, the lobbying costs, direct and indirect bribes, years of waiting that even the big developers have to go through before they can push into office electeds favorable to their projects etc. are all costs that get recycled back to the public – those who ultimately buy the dwellings.

But that is not the only problem with growth restrictions. Which brings us to…

DP4’s question:

Can the Antiplanner explain to us the factors that inspire states to adopt growth management planning?

The same reasons that inspire entire nations to erect protectionist trade barriers and immigration policies – they want to reduce the influx of outsiders to a trickle so that they can keep exclusive access to their paradise.

It is a shortsighted mentality because, in the end, like protectionist legislation at the national level, protectionism ultimately also hurts the very locality that implements it. But such a policy, although detrimental, would at least be legitimate were it not for the fact that the growth management planning policies in this case are based on tyrannizing a minority of local low density zoned owners.

In the end, the central moral issue with land use regulation is: Is it appropriate for the majority to have enough power to determine through land zoning regulation who becomes very rich (i.e. zoned high density urban) and who looses his property rights (i.e. Portlanders outside the UGB)?

And the central pragmatic issue for the collective is: How is individual productivity in such a society affected when wealth is more associated with winning the regulation lottery (land use regulation in this case) rather than productive effort? What conclusions should I derive when I find it equally profitable to become wealthy through regulation rather than continue to lead the cancer research company I co-founded? There is a reason why once successful countries loose their productivity and take a turn towards decline; and weakening property rights are a significant factor in this decline.

Lorianne,

Doesn’t growth management in Hawaii date all the way back to the 1960s?

Wowie. Lots of objectivist talking points in there, but one actually plays out on the ground in a real way, among real people and not fantasy characters:

In the end, the central moral issue with land use regulation is: Is it appropriate for the majority to have enough power to determine through land zoning regulation who becomes very rich (i.e. zoned high density urban) and who looses his property rights (i.e. Portlanders outside the UGB)?

Yes.

Why? The crushing, widespread defeats of the Private Property Rightists’ anti-zoning initiatives.

Oh, and the fact that there are zero on the ballot this year.

Of course, as I’ve said many times here, we need to figure out how to accomodate the very few who can’t take advantage of their land. That how doesn’t include taking away the vast majority’s property rights so a tiny minority can exercise theirs. Maybe they’ll do a gravel pit in the midst of a subdivision – everyone wins!!!!! *heart*!!!!!!

DS

Wowie. Lots of objectivist talking points in there, but one actually plays out on the ground in a real way, among real people and not fantasy characters:

Real way indeed. So what happens in the real world is that resourceful people adapt and do the next best thing there is: They use regulation to their advantage. They abandon more productive activities (like seeking new cancer cures) and instead passively invest in the resulting limited supply of real estate and make money the easier way – at the public’s expense…. …And the public essentially gets what they asked for. So what is the public going to do next? Attempt to regulate how people make money in real estate? Capable people will find yet other ways to take advantage of the new regulation. Just look at the high proportion of real estate barons amongst Europe’s regulated [ha!] rich. It is very difficult to regulate capable people into a corner. At best you change the types of skills needed to succeed – from creativity and innovation which benefits everybody – but to a different extent – to more corrupt wealth redistribution based on who has connections to whom in the political power structure. Regulation will never catch up. Creative people will always be one step ahead.

Maybe they’ll do a gravel pit in the midst of a subdivision…/

The divisive issue is not total abolition of zoning but rather the separation into those who believe that there is not enough zoning vs. those who believe that there’s already way too much zoning.

“As prk166 would agree, Denver has ‘areas of stability’ and ‘areas of change’. The rules are clear for both categories. There is nothing ’sudden’ about it in Denver or anywhere else. ”

Actually, I have no idea what these areas of stability and change are? Gov’t imposed? Part of the regional plan? More in general and how the market is behaving in terms of who is buying and selling? Or do you mean in terms of density and how that can change? I’m not picking up on where that’s going.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJW8jKZ1n-M&feature=related