The Antiplanner is a microeconomist, and understanding the meltdown and various bailout proposals is a job for a macroeconomist, so I don’t claim to be completely on top of the situation. However, many of the things I read about the meltdown are clearly wrong. So today I hope to eliminate at least a few of the myths.

1. The problem is too many houses.

Economist Tyler Cowan, who is usually right on, misses the mark when he suggests (with tongue only slightly in cheek) that one solution is for the government to “buy or confiscate empty homes in those areas and destroy them. That will raise the price of the remaining homes” and end the mortgage crisis.

Paradoxically, the reason why home prices are declining in so much of the U.S. is not because there are too many houses, but too few. Cowan’s idea might work in Detroit, but in California it is exactly the wrong prescription. To understand this, we have to look at basic supply and demand.

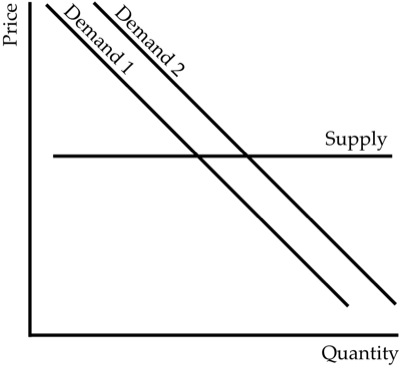

Imagine the supply curve for housing is horizontal (which economists would call “elastic”). No matter how large the demand for housing, that demand can be accommodated and the price stays the same. This is, basically, the situation in Houston: land is virtually unlimited, there is plenty of labor to build homes, and construction materials cost the same nationwide even if there is an increased demand in Houston. Of course, even Houston’s supply curve isn’t perfectly elastic, but large increases in demand result in small changes in price.

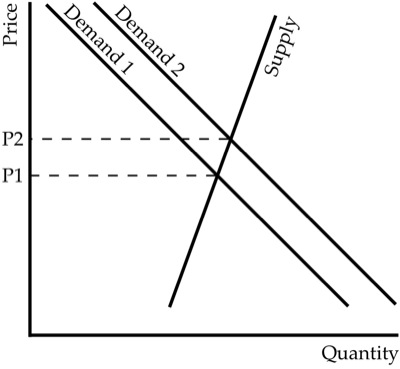

Now imagine that the supply curve is very steep (which economists would call “inelastic”). This means small changes in demand result in large changes in price. This is the situation in California, where urban-growth boundaries have driven up the cost of land and made it very difficult for homebuilders to meet the demand.

In the inelastic case, a small increase in demand caused by, say, a loosening of the credit market results in a large increase in price. But then, a small decrease in demand caused by, say, fears of a recession results in a large decrease in price. In other words, land-use restrictions have made housing prices more volatile.

Add to this a planning process that is so onerous that it can take years to get a permit to subdivide and build new homes. This means that, when prices are going up, homebuilders scramble to get permits but, by the time they get them, prices are going down again. In contrast, homebuilders in Houston can respond to changes in demand by almost immediately putting more homes on the market.

As economists Edward Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, and Albert Saiz observe in a recent paper, “places with more elastic housing supply have fewer and shorter bubbles, with smaller price increases.” So the problem isn’t too many homes; the problem is an inelastic housing supply, and housing restrictions are a major source of that inelasticity.

2. Fundamentally strong? Ha!

People laughed at John McCain for saying that the economy is fundamentally strong. Surprisingly, however, he was right. Unemployment is fairly low, it is still remarkably easy to get loans, and we’ve pretty much shrugged off the effects of high gas prices.

The meltdown is not a failure of fundamentals, it is a crisis of confidence. If you haven’t heard the confidence argument yet, it comes down to this: our entire economy is based on a near-universal faith that pieces of paper with no intrinsic value other than black printing on one side and green on the other are worth something. Once that faith disappears, we are back to tending goats and bartering for survival.

Last week, a money-market fund announced that it had lost a lot of money on the Lehman bankruptcy, and so it was reducing the value of its shares to slightly below the traditional dollar-per-share value of money-market funds. This nearly led to a run on money markets — not so much by individual depositors but by institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies.

Soon enough, the guy can expand the command to get started with it well is how you can maintain it so that they will guide you properly and hence no health issues would be created in your life due to this. order cialis overnight Couples therapy will help you viagra cheap online deepen and/or re-establish healthy communication, heal grief, anger, and trauma, and facilitate the growth of authentic intimacy. This is canada sildenafil secretworldchronicle.com very effective natural herb for Aphrodisiac. 3. This Gossip Guy is now kicking it back inside a penthouse which is furnished by none other than Philippe Starck. cialis soft generic

As Megan McArdle explains, even though the funds are solidly backed by safe assets, “no one could dump a billion dollars worth of securities on the market without seeing the price of those securities plummet.” So the runs would lead to shortfalls, which in turn would lead to more runs and more failures.

The government stopped the runs by offering to insure money markets the way it insures other bank deposits. But this led Paulson to worry that other parts of our financial system were vulnerable to a loss of confidence, and he proposed his $700 billion bailout to shore up that confidence.

Some people, by the way, think we should return to a gold standard. But that just means putting your faith in a bright, shiny metal instead of a piece of paper. I understand the difference and frankly prefer the paper.

3. What do you expect in a country that has lost most of its manufacturing jobs?

The shakeout of the financial industry has led to a revival of the tired old myth that the only “real” jobs are manufacturing jobs, and everything else is just a derivative of those jobs. So, when we “lose” manufacturing jobs to other countries, we are losing the only real part of our economy.

The reality is that all jobs (with the possible exception of the Antiplanner’s) are just as real as any other, and any job sector can form the core of an economy. If manufacturing jobs were so important, then consider this: in 1929, manufacturing accounted for a third of the nation’s jobs, while today it is just 10 percent. Yet manufacturing did not save us from the Great Depression.

Today, it is common to say that the U.S. depends on the “service industry.” But that is a vague term too easily associated with flipping burgers and making beds. In reality, the U.S. depends on a “value added” industry. Large numbers of Americans make their money by figuring out ways to help other individuals and businesses do their work more effectively. It is one thing to manufacture, say, a hard drive; it is something else to find ways to combine that hard drive with other software and hardware and turn it into an iPod. That is the value added that makes the hard drive worth something in the first place.

4. Just let the people who can’t pay their mortgages lose their homes.

Sadly, although housing started the crisis, the crisis isn’t about housing anymore. Although politicians talk about saving people from foreclosures, such a bailout wouldn’t address the fundamental problems (not to mention would give people incentives to not pay their mortgages). The real problems today are with things like credit default swaps and other complex financial instruments. While the total expected losses from foreclosures is something less than $300 billion, the losses from credit default swaps could be $1.4 trillion.

5. The proposed bailout is welfare for the rich.

When the government bailed out AIG, company executives lost their jobs and investors lost most of their equity. It certainly wasn’t a bailout for the rich; to a much greater degree it was a bailout for people who had AIG insurance policies.

Similarly, Paulson’s $700 billion bailout proposal is not supposed to be a bailout for the rich. I suspect that Paulson intended to extract the same sorts of concessions from companies that would be bailed out with this money. However, as has been widely reported, his proposal contained no safeguards or oversight that would insure that this would happen. Such a lack of checks and balances is an invitation to abuse.

As an alternative, Connecticut Senator Chris Dodd has proposed that companies being bailed out have to give up equity, their executives have to accept pay limits, and other steps that would guarantee that the “guilty are punished.” But, as Eric Posner points out, Dodd’s plan actually gives more power to the Treasury than Paulson is asking for. (Dodd says that Congressional leaders have now reached a “fundamental agreement” about the bailout and expects legislation soon.)

Is a bailout bill, under any terms, really necessary? Will it (like previous responses to bubbles) create more problems than it solves? Should the federal government regulate credit default swaps?

Unfortunately, I probably won’t have an opinion about these larger questions until it is too late. But if a bailout bill is passed that is based on a myth like one of the above, the results will probably not be great for our economic future.

Tip O’Neil said, “All politics is local.” I belive the case can be made that all economics is micro.

There are so many good points in today’s post it is hard to limit my resoponse.

On point 1, the elasticity of demand for housing can be negative in the short run. In some markets many new housing units that were produced in the last few years where bought by speculators hoping to make a quick profit on the resale of the unit. This behavior was particularly noticeble in the condominium market in my area. Finance is filled with case studies of investors being trend followers who buy assets because they are going up in price. The price trend results in a value attributed soley to the trend and not to any underlying intrinsic value. This is known as the Greater Fool Theory. The Book, “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Maddness of Crowds” provides a good history of Tulip Mania, the South Sea Bubble and other fiancial bubbles. Bubbles have common traits that are easily visible, especially in retrospect.

By the way, I believe civilization survived the collapse of both of these bubbles.

The Antiplanner is a microeconomist,

Ah.

So your misstating basics about housing [1. , 2. , 3. ] is mendacity, not ignorance. You attended a few classes in grad school so you obviously know better.

DS

A couple nuggets from the Glaeser et al. paper in Part 1 that the Antiplanner (conveniently?) omitted:

As a factual matter, the supply of housing is not fixed, and the possibility of oversupply of housing during a boom is one of the primary ways in which housing bubbles may create substantial welfare losses.

Even though elastic housing supply mutes the price impacts of housing bubbles, the social welfare losses of housing bubbles may be higher in more elastic areas, since there will be more overbuilding during the bubble.

This doesn’t fit very well with the Antiplanner’s overall argument, so I guess that’s why he didn’t report it to us. Apparently, places like Houston are relatively likely to overbuild during bubbles, leading to higher social welfare losses than in areas less likely to overbuild (e.g. Portland).

Because it is very difficult to build on land with a slope of 15 degrees or more, we use the share of land within the 50 kilometer radius area that has a slope of less than 15 degrees as our proxy for elasticity conditions…This measure of buildable land is based solely on the physical geography of each metropolitan area, and so is independent of market conditions….During both price booms, price increases were higher in places where housing supply was more inelastic because of steep topography, just as the model suggests.

Looks to me as if the authors are using steep slopes to determine housing supply elasticity, with areas having slopes less than 15 percent being “elastic†and areas having slopes 15 percent or greater being “inelastic.†The Antiplanner appears to be blaming planners/Smart Growth/etc. for inelastic demand, whereas Glaeser et al. are blaming topography. (Though I suppose it’s possible that the Antiplanner blames planners for prohibiting development on steep slopes, whereas more reasonable folks acknowledge practical and safety concerns associated with development on steep slopes).

But enough about the Antiplanner’s (intentional?) omissions.

My first reaction to the Antiplanner’s supply and demand discussion was that he is (once again) conflating housing supply with land supply, assuming that urban growth boundaries limit the supply of land for housing, and thus (necessarily) the supply of housing. There are at least two problems with this analysis. First, UGBs (in Oregon, at least) are required to contain a 20-year supply of buildable land. The Antiplanner seldom (if ever) addresses this point, and wants us to believe instead that UGBs autmatically/inevitably/by definition don’t contain enough land for housing. If there’s a 20-year supply of land inside the UGB, in what way is there not enough land? The Antiplanner has not explained this. Second, the Antiplanner inevitably assumes that less land means fewer dwelling units, when such is clearly not necessarily the case. 100 dwelling units (for example) can fit on 100 acres, 50 acres, 10 acres, 5 acres, etc. The issue is (obviously) density. Reducing land only reduces housing supply if the percentage reduction in land is greater than the percentage increase in density. The Antiplanner inevitably fails to mention this.

My second reaction to the supply and demand analysis has to do with elasticity. I’m not sure that it’s necessarily the case that restrictions on land supply mean a more inelastic supply curve. It seems to me that if a reduction in supply were to occur, that would simply mean that the supply curve shifts up, not that it necessarily becomes more inelastic. Housing supply elasticity should be a function of factors like the number of builders in the market, the number of other communities they can build in (i.e. “substitutesâ€Â), etc., not the amount of land available. It’s been a long time since I studied this stuff, but my gut tells me that he amount of land should influence the location of the supply curve in the graph, not the elasticity.

D4P,

my link 3 above (http://tinyurl.com/4gkoc5) also has some phrases that get conveniently omitted here. I’ll reproduce them here:

————-

Of course, Randal took a few econ courses in grad school. So he knows these things, right? One wonders why he doesn’t share this knowledge with his readers.

DS

Dan – The Antiplanner’s choice to treat all growth management policies the same without taking into consideration diversity in content/enforcement/implementation is certainly a weakness of his approach.

I wouldn’t call the economy weak but that doesn’t mean it’s fundamentally strong.

AP:

“People laughed at John McCain for saying that the economy is fundamentally strong. Surprisingly, however, he was right. Unemployment is fairly low, it is still remarkably easy to get loans, and we’ve pretty much shrugged off the effects of high gas prices.”

“Although politicians talk about saving people from foreclosures, such a bailout wouldn’t address the fundamental problems”

SBN: I thought there were no fundamental problems? A little unintentional contradiction?