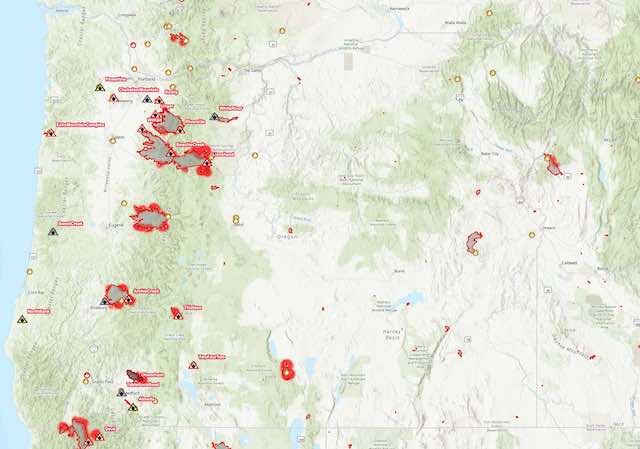

Despite rain in the valleys and snow in the mountains, wildfires are still smoldering in Oregon and people are still trying to blame those fires on the lack of government spending on logging or prescribed burning. Yet increased logging wouldn’t have stopped western wildfires this year, a number of researchers told reporters in an article jointly written by the Oregonian, Oregon Public Broadcasting, and Propublica.

“The belief people have is that somehow or another we can thin our way to low-intensity fire that will be easy to suppress, easy to contain, easy to control,” retired Forest Service researcher Jack Cohen told the reporters. “Nothing could be further from the truth.” Continue reading