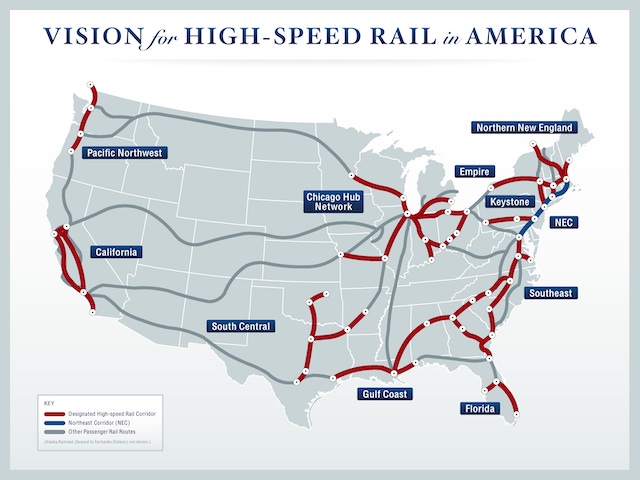

After promising that their Dallas-Houston high-speed rail project would be built solely with private funds, Texas Central backers are sending out feelers about getting a federal guaranteed loan to build it. A letter from the company chairman to Texas state senator Robert Nichols says the project “hit a snag” due to the coronavirus, but “monies we hope to receive from President Trump’s infrastructure stimulus” could make it “construction ready this year.”

The fact that President Trump doesn’t have any infrastructure stimulus money is just a minor detail. Company officials cited possible loans through the Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing (RRIF) or the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) programs. However, neither of these loan programs are large enough for the kind of project contemplated by Texas Central.

Texas Central was originally supposed to cost $10 billion. Then it was going to cost $20 billion. But the letter to Nichols now admits that the project may cost $30 billion. Continue reading