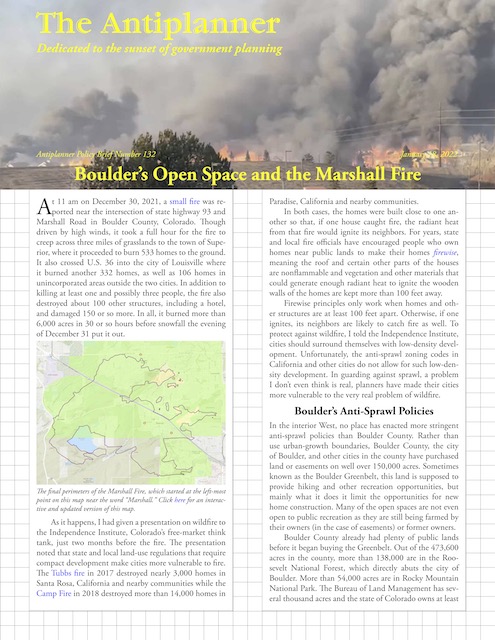

At 11 am on December 30, 2021, a small fire was reported near the intersection of state highway 93 and Marshall Road in Boulder County, Colorado. Though driven by high winds, it took a full hour for the fire to creep across three miles of grasslands to the town of Superior, where it proceeded to burn 533 homes to the ground. It also crossed U.S. 36 into the city of Louisville where it burned another 332 homes, as well as 106 homes in unincorporated areas outside the two cities. In addition to killing at least one and possibly three people, the fire also destroyed about 100 other structures, including a hotel, and damaged 150 or so more. In all, it burned more than 6,000 acres in 30 or so hours before snowfall the evening of December 31 put it out.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

As it happens, I had given a presentation on wildfire to the Independence Institute, Colorado’s free-market think tank, just two months before the fire. The presentation noted that state and local land-use regulations that require compact development make cities more vulnerable to fire. The Tubbs fire in 2017 destroyed nearly 3,000 homes in Santa Rosa, California and nearby communities while the Camp Fire in 2018 destroyed more than 14,000 homes in Paradise, California and nearby communities.

The final perimeters of the Marshall Fire, which started at the left-most point on this map near the word “Marshall.” Click here for an interactive and updated version of this map.

In both cases, the homes were built close to one another so that, if one house caught fire, the radiant heat from that fire would ignite its neighbors. For years, state and local fire officials have encouraged people who own homes near public lands to make their homes firewise, meaning the roof and certain other parts of the houses are nonflammable and vegetation and other materials that could generate enough radiant heat to ignite the wooden walls of the homes are kept more than 100 feet away.

Firewise principles only work when homes and other structures are at least 100 feet apart. Otherwise, if one ignites, its neighbors are likely to catch fire as well. To protect against wildfire, I told the Independence Institute, cities should surround themselves with low-density development. Unfortunately, the anti-sprawl zoning codes in California and other cities do not allow for such low-density development. In guarding against sprawl, a problem I don’t even think is real, planners have made their cities more vulnerable to the very real problem of wildfire.

Boulder’s Anti-Sprawl Policies

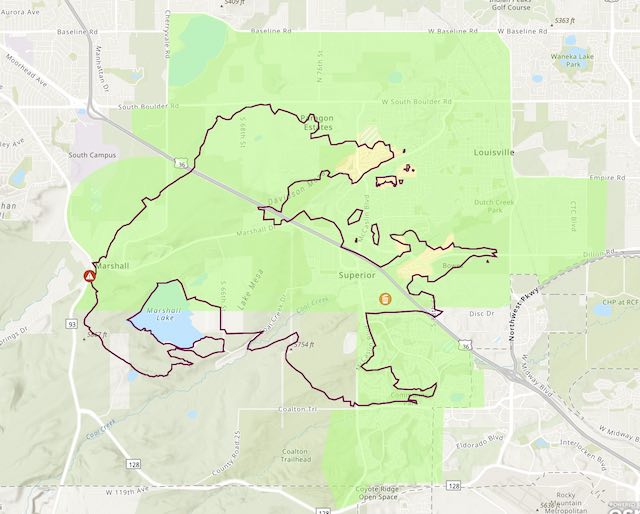

In the interior West, no place has enacted more stringent anti-sprawl policies than Boulder County. Rather than use urban-growth boundaries, Boulder County, the city of Boulder, and other cities in the county have purchased land or easements on well over 150,000 acres. Sometimes known as the Boulder Greenbelt, this land is supposed to provide hiking and other recreation opportunities, but mainly what it does it limit the opportunities for new home construction. Many of the open spaces are not even open to public recreation as they are still being farmed by their owners (in the case of easements) or former owners.

Map of public lands and open spaces in Boulder County. Grey areas are cities, outside of which the only private lands not protected as open spaces are white. Click here to download a PDF of this map.

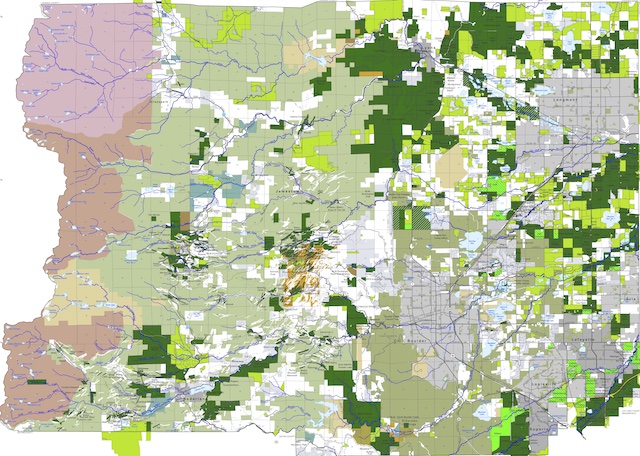

Boulder County already had plenty of public lands before it began buying the Greenbelt. Out of the 473,600 acres in the county, more than 138,000 are in the Roosevelt National Forest, which directly abuts the city of Boulder. More than 27,000 acres are in Rocky Mountain National Park. The Bureau of Land Management has several thousand acres and the state of Colorado owns at least 2,000 acres. Before the cities or county bought a single acre of open space, well over a third of the county was federal or state land and nearly all of it was open to recreation.

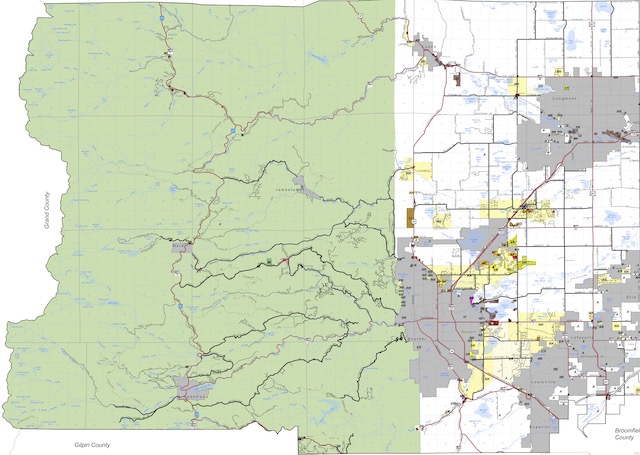

Boulder County zoning map: grey is cities; green is zoned Forestry; white is zoned Agricultural; nearly all of the yellow is Rural Residential with 1-acre lot sizes but a small portion of the yellow is Suburban Residential with 7,500-square-foot minimum lot sizes. Click here to download a PDF of this map.

In addition to buying open space and easements, Boulder County has zoned much of the remaining private land outside of city limits for non-residential uses. Ten incorporated cities in Boulder County occupy about 12 percent of the county’s area but house 87 percent of the county’s population, with the other 13 percent being mostly in rural residential zones.

Not counting the cities, 95.2 percent of the county is zoned Forestry, Agricultural, or another zone that has 35-acre minimum lot sizes. Around 4.2 percent is Rural Residential or another zone that has 1-acre minimum lot sizes. Less than 0.3 percent is zoned multifamily or another zone that allows more than one home per acre, averaging 7,800-square-foot minimum lot sizes. Slightly more than 0.3 percent is zoned for industry, commercial, or other non-residential uses. A comparison of the zoning map with the open space map reveals that at least some of the areas zoned residential are in open spaces, which means they will never be developed unless the city or county change their open-space policies.

These actions and policies have made Boulder County one of the most expensive housing markets in the nation. According to the Census Bureau, the county’s median home value in 2019 was $592,000, more than any other county in the nation that is not in a coastal state. Only 16 counties in California, three in New York (all in New York City, whose five boroughs are also five counties), two in Hawaii, and one each in Massachusetts, Virginia, and Washington were more expensive.

According to Zillow, the median value of Boulder County homes had grown to $728,000 by November 2021. For comparison, the median value of homes in the United States as a whole was $240,500 in 2019 and $316,400 in November 2021.

Open Space and the Marshall Fire

The three miles of grasslands crossed by the Marshall Fire before it reached the town of Superior were almost all city or county open spaces. A small portion that was not was zoned agricultural. As noted, despite high winds, the fire moved across this area at a moderate pace of about 3 miles per hour.

The first homes to be burned by the fire were in northwest Superior. The land to the left of the homes is open space that is closed to public recreation; the land to the right is the shopping mall with Target.

The first homes to be reached by the fire were in northwest Superior. Due to the high cost of land, these homes were crammed together on 3,000- to 4,000-square-foot lots. Most of the houses ranged in size from 1,230 to 2,050 square feet, although a few were 2,550 and at least one was nearly 2,900 square feet. Zillow estimates that the homes were worth between $573,000 and $765,000. Since individual building lots in Superior sell for several hundred thousand dollars, perhaps half the value of those homes was in the land.

This image from Google streetview shows the narrow gaps between the homes in northwest Superior.

Fitting even two-story 2,000-square-foot homes on 3,000-square-foot lots doesn’t leave a lot of land left over, especially considering the city appears to require 25-foot setbacks from the street. Photographs show only about ten feet of spacing between the homes. This is not what Superior needed as its first line of defense against the fires. Not a single house in this neighborhood survived.

All of the homes in the previous two images were destroyed.

Having passed through these homes, the fire attacked a shopping center that included a Super Target and a Costco. Being surrounded by parking lots, these areas were the epitome of firewise. Aerial photos show that some of the solar panels on the roof of the Target caught fire, but the Costco and most other structures appear completely undamaged.

This gasoline station survived while nearby homes did not, demonstrating the value of firewise design.

South of the shopping center, the fire passed through a neighborhood of homes that were not packed as densely as the first neighborhood. Many of these houses burned, but some that were on larger lots survived. Curiously, a Phillips 66 fuel station surrounded by asphalt survived while most of the homes around it did not. Gas stations are often thought to be vulnerable to fires, but they are apparently more firewise than most homes on smaller lots.

The center home in this photo was the newest in the neighborhood and was saved by the fact that the owners had not yet grown or installed any trees or shrubbery. All of its neighbors shown in this photo burned to the ground.

At the same time, the fire crossed U.S. 36 to the north, entering a rural residential neighborhood called Paragon Estates. Many of these homes were built on 1-acre lots. Being on a large lot was no guarantee of safety. One home that appears to be built of stucco with a completely non-flammable roof survived, as did a new home that hadn’t yet had landscaping installed. Other homes burned because they were surrounded by trees and other vegetation. But it is notable that firefighters were able to use the spaces between these homes as a firebreak and halt the northerly progress of the fire.

The trees and vegetation around this home, located not far from the one in the previous photo, were enough to ensure its destruction.

East of Paragon Estates, the fire entered the town of Louisville. Many of the homes in the fire’s path were built on 7,000-square-foot lots, but some rows of homes were separated from others by greenspaces. In one neighborhood, two homes built on 18,000-square-foot lots survived while nearly all of their neighbors on 7,000-square-foot lots did not. Once a row of homes caught fire, most of the houses in that row burned, but firefighters were able to use the greenspaces between the rows as firebreaks.

The two homes at the bottom of this photo are on 18,000-square- foot lots. They survived, while most of their neighbors on 7,000- to 8,000-square-foot lots did not.

As in Superior, large buildings such as hospitals, retailers, and offices often survived, being surrounded by asphalt instead of flammable trees or nearby homes.

Considering that freak winds of 80 to 100 miles per hour, with gusts of up to 115 miles per hour, were reported during the fire, it is a credit to firefighters that the fire claimed only 6,000 acres and under a thousand homes. But this is also due to the many greenspaces or large parking lots within the cities that firefighters were able to use as fire breaks. While those in-city greenspaces helped stop the fires, the county Greenbelt made the results of the fires worse by forcing high-density developments into the cities.

Boulder’s Greenbelt policy has the apparent virtue that it at least compensated many of the rural property owners for giving up their rights to develop their land, though owners of the remaining land zoned Forestry and Agriculture might disagree. However, however it was done, removing most of the land in the county from the possibility of development has completely warped the housing market. Existing homeowners were winners while anyone who bought homes in more recent years were losers. This system increases wealth inequality without notably improving the county’s quality of life.

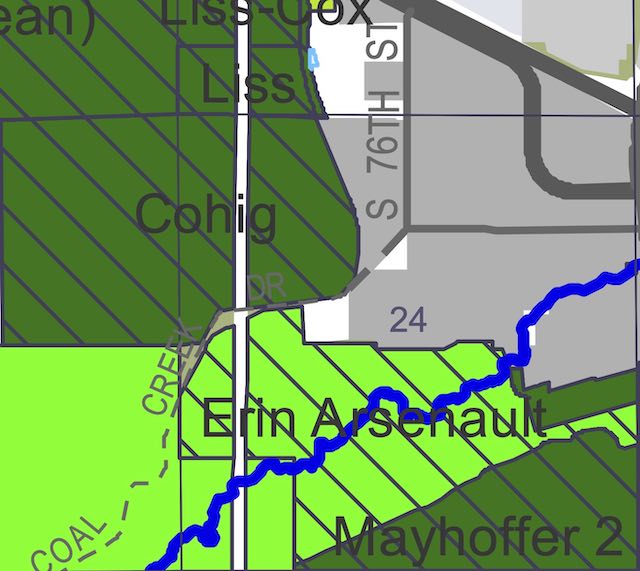

In this detail from the county open-space map, the area marked “S 76T” is where the first homes that burned were located. The greens are city or county open spaces and the diagonal lines indicate these particular open spaces were closed to the public. The purchasers of homes in this area may have thought the open spaces to be a plus; they turned out to be a minus.

The Marshall Fire revealed one more problem with the policy: its lack of resiliency in the face of natural disasters. A close look at the county open space map reveals that the land immediately west of the Superior homes that burned is county owned but not open to the public, probably because the county bought it with the proviso that the previous owners are allowed to continue to farm it. There was no point in buying this land except to limit the amount of developable land in the county.

To reduce fire hazards, the county and cities within the county should sell or give up easements for all land within a two-mile strip around all cities in the county. All land within this strip should be rezoned to 1-acre minimum lot sizes with requirements that homeowners in this buffer strip manage their properties to firewise standards. Such land should be available to be annexed by the cities and as such annexations take place the two-mile buffer strip should be moved, rezoning land as needed. This will help alleviate housing affordability problems as well as make homes and other structures less vulnerable to wildfire.

“compact development make cities more vulnerable to fire”

No it’s what you build your buildings out of. Brick, stone and concrete does not go up in flames, Wood…….does.

1666 London fire; Self-reliant community procedures were in place for dealing with fires, and they were usually effective. “Public-spirited citizens” would be alerted to a dangerous house fire by muffled peals on the church bells, and would congregate hastily to fight the fire. Never less, it spread anyway, Post-fire, London rebuilt…..The reconstruction also saw improvements in hygiene and fire safety. Most importantly, buildings constructed of brick and stone, not wood.

Question Why do we build houses out of wood in places where wildfires are ubiquitous. Same answer why Chernobyl had no containment domes or uses graphite instead of water moderators……..”it’s cheaper”

Sure …. Ancillary methods aside. Economics of scale make things “Cheaper” so a surge in demand for oh I don’t know… Hurricane resistant, fire resistant homes…… is a huge time saver. Would also save you and insurance companies a fortune. Why not build Concrete homes the way we build wooden ones

instead of 2×4’s we have pre-stessed concrete posts.

Benefit:

– Concrete walls do not rot: when exposed to moisture by wind-driven rain, diffusion, or airflow. They are therefore largely resistant to biological processes. Like termites. Unfortunately, termites can destroy wood houses and cause thousands of dollars in repairs.

– Concrete provides healthy environments with fewer airborne allergens, molds, and toxins; (though concrete dust is easily dealt with by polishing or sanding), Wood is a breeding ground for such. Sure concrete can suffer molds, but they’re easily repaired by bleaching. 20-50% of what makes a wood house isn’t wood, it’s epoxies, sealants, VOC’s, hydrocarbons and chemicals which slowly leach thru the houses’ lifecycle.

– thermal mass makes them better insulated reducing energy costs.

– Noise insulation

– Durability makes them less prone to risks from natural disasters….

While concrete houses can cost more to build; They save money over time with lower utility and maintenance expenses.

Another strategy, build a wooden house and spray it with concrete.

Continud: Around 10bn tonnes (pdf) of concrete are manufactured each year: a staggering one cubic metre for every person on Earth. And every year 700 million tons gets sent to landfills globally……..why not cut and recycle it as new housing.

Constructed with over 600,000 lbs of recycled materials, this is the house that Boston’s Big Dig came from.

https://www.archdaily.com/24396/big-dig-house-single-speed-design

Ugly? Maybe, but architecture design aside.

2018 Fact Sheet shows: 600 million tons of construction and demolition debris were generated in the United States…..Enough to build 200,000 homes….