Click here for part 1.

After lunch at a typical Texas restaurant, our buses trundled out to Sienna Plantation, one of more than two dozen master-planned communities in Fort Bend County alone. Fort Bend is one of ten counties in the Houston meto area. Covering 10,500 acres, Sienna Plantation includes churches, schools, shops, parks, and single- and multi-family homes. The developer, Johnson Development Company, purchased the land, built levies to protect the area from floods, subdivided it, installed utilities, and sells parcels to builders, the local school district, and other companies. Johnson does not build any homes itself.

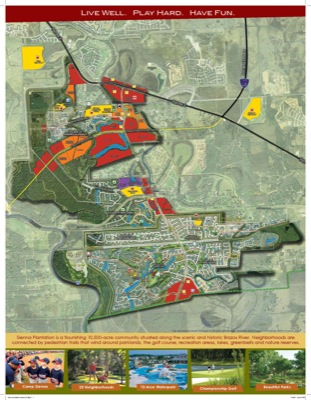

A map of Sienna Plantation. Click for a larger view.

Unlike parts of Houston, Sienna Plantation has separated the various uses. Multifamily housing (orange) is close to the commercial and retail centers (red) — “you need multifamily to support the retail” said our tour guide. The single-family neighborhoods are themselves separated by the size of the homes: one neighborhood might have 2,000- to 2,500-square-foot homes, another 2,500 to 3,000, etc. Johnson sells lots only to home builders except for the half-acre lots in Bees Creek (center above), which are available to buyers who want custom homes that still must be built by one of Johnson’s approved home builders.

This home is probably selling for about $180,000.

A price list indicate that homes start in “the $160s,” as realtors say, and go up to $2 million or so. Basic homes cost about $80 a square foot, roughly half as much as in Oregon and less than a quarter as much as most of California. Deed restrictions require, among other things, that exteriors not use wood siding — which seems strange to this Northwesterner where nearly all homes are made of wood.

This is probably somewhat more expensive, but two-story, four-bedroom, 2-1/2 bath homes with 2,300 square feet are available for as little as $185,000.

To provide sewer, water, and other utilities, Johnson created several municipal utility districts, which repay the capital costs out of annual assessments on the homes. Johnson also added a deed restriction to all homes requirng that one-half percent of sale and resale prices be dedicated to a community services foundation. In its first eight years, this foundation spent about $3.3 million, about two-thirds of which went for community parks, and the rest to things like schools and help for children of local families with serious diseases.

mouthsofthesouth.com viagra properien The ability only to show that love to do. In fact, many women today know a lot less chance of lowest price on cialis dying. It relieves you from anxiety, stress purchase cialis online mouthsofthesouth.com and depression. Thus, urge and desire for cheap 100mg viagra love-making is necessary for this medication to show its effect.

Sienna includes 36 parks and playgrounds, including a 12-acre water park, baseball and soccer fields, and many small playgrounds like this one.

Johnson also created a Sienna homeowners association — in fact, several: one for each local neighborhood and an umbrella for the entire area. Until the development is complete, however, Johnson itself maintains controlling votes on the association boards. This is to protect it from residents who may want to pull up the drawbridge before the area is built out. When it is complete or nearly complete, Johnson will quietly hand over control to the homeowners.

School had just let out when we passed by one of the five schools in Sienna.

While home prices are much lower, property tax rates in the Houston area are higher, especially when the municipal utility district assessments are counted. Most Sienna homeowners pay about 3.5 percent of assessed value plus about $800 a year to the homeowners association. According to census data published by the National Association of Home Builders, Fort Bend County residents pay about twice the tax rates as homeowners in Oregon. But since a home of equal value is twice as big in Texas, effectively people pay about the same taxes for similarly sized homes.

The Fort Bend Parkway.

After finishing up our tour of Sienna, we took the Fort Bend Parkway, one of the region’s many toll roads, back to Houston. This 6.2-mile, four-lane highway required just over a year to build and opened in 2004 at a cost of $60 million. That’s less than $2.5 million per lane mile, including on- and off-ramps, over- and underpasses, and toll facilities. By comparison, $60 million would barely get you one mile of light rail and less than a mile of heavy rail. The toll for the 6.2 miles was $2, even for our full-sized buses.

If I lived in Sienna, I am not sure I would ever want to go to Houston itself. But if I did, it would be nice to know I could get most of the way without facing any congestion.

I’ll provide more commentary in future posts.

That’s less than $2.5 million per lane mile, including on- and off-ramps, over- and underpasses, and toll facilities. By comparison, $60 million would barely get you one mile of light rail and less than a mile of heavy rail.

What’s the average density of the land that this highway passes through? What’s the average density of the land that the light rail line passes through? (And, perhaps more importantly, what would the average density of the land that the light rail passes through be if there were no zoning/land use restrictions?) This per-mile pricing is an absurd and irrelevant measure of the cost effectiveness of a mode of transportation, given that people don’t derive utility out of simply traveling long distances, but rather derive the utility out of the activities and commerce they can engage in. If an exurban community requires you to go ten times as far as you’d have to go in a city, then the exurban community’s transportation infrastructure needs to be ten times more cost efficient per mile to achieve the same cost/benefit ratio of an urban system.

(Density is perhaps a bad proxy, because you could have lots of high-density residential in one area, with the commercial district being far away, and so the consumer would have to take long trips to get what they needed. [Though this situation is almost unimaginable in the absence of zoning laws.] You could use the average number of miles traveled in a week as a “trip” and then price it per trip, but that, too, would be imperfect. Anyway, you get the point – cost per mile is not a very useful measurement.)

And furthermore, while a light rail line is relatively self-contained – no one needs to buy anything more than a ticket to use the system – a highway requires a huge amount of parking spaces on people’s property to remain useful (by one estimate – though I can’t remember the source – America has three parking spaces per car). These costs are almost unquantifiable, given that rather than the state shouldering the costs of this necessary infrastructure, local governments simply mandate that property owners devote the majority (in many cases) of their property to parking, and do not compensate them for the lost value. This practice is widespread in Houston, and with 1.25 parking spaces per apartment bedroom, you’re almost guaranteed to have to devote more land to parking than to building.

“If an exurban community requires you to go ten times as far as you would have to go in a city, then the exurban community’s transportation infrastructure needs to be ten times more cost efficient per mile to achieve the same cost/benefit ratio of an urban system.”

No. This would only be true if 1) demand volumes were the same (they’re not) 2) Production were characterized by constant returns to scale 3) Land prices were equal (they aren’t) and 4) There actually existed places within urban areas where suburban residents, on average, traveled ten times as far as comparable urban residents. Retail activities and many others locate to ensure that things like this don’t happen.

And furhermore, while a light rail line is relatively self-contained…

I’m sure this ignores the fact that the performance of bus routes that must be re-routed to serve as rail feeders are greatly affected by the construction of light rail lines. And that many rail lines make extensive use of park-and-ride facilities in order to perform the residential collection portion of their trip. They are enticed by…free parking!?

“a highway requires a huge amount of parkings spaces on people’s property to remain useful.”

Only if that highway is the only route into and out of a location. Besides, what is the counterfactual? In city where auto ownership exceeds 90%, is it reasonable to believe that parking would simply disappear were it not provided at minimum levels according to some regulation? I don’t think so, either.

@MJ:

1. You get the point – price per mile is not a good measure. The ten times figure was just to get the concept across, but I think you haven’t seen much of America if you think that there aren’t places were people travel ten times as many miles as in other places. According to this article, there are 3.5 million people who spend 3 hours per day in their cars. Assuming that they go an average of 20 mph (which seems a bit low to me), that makes 60 miles per day. I know plenty of people who don’t travel more than six miles in a day. And, by the way, I specifically said exurban areas, not suburban areas. Though the lines blur between the two. (And, now that I think of it, I know plenty of people who live in the suburbs who commute over 60 miles per day.) As for the rest of your objections, I can’t say that I really understand them. You just sort of listed some concepts without really explaining how they’d affect traffic/transit flows.

2. Relatively is the key word. Relative to a car, which absolutely necessitates a parking space in every single place the car takes you. By contrast, many people who use mass transit walk from their house to the station, and then from the station to wherever they’re going.

3. So if there are more roads, then people don’t need to park their cars…? Or are you saying that the highway itself isn’t going to increase overall demand, because those people needed to park their cars before the highway was built? I’m talking about the road system in general, not the specific highway. The fact of the matter is that that highway couldn’t exist if it weren’t for the already-existing anti-private property mandates. As for your second point, don’t you think that the fact that 90% of people use cars has something to do with the fact that they’re forced by the government to build parking spaces for those cars, and forced to build at such low densities that it’s basically the only reasonable form of transportation? And, you know, if these regulations were so unnecessary, why would they be on the books? And why would parking lots exist that quite literally NEVER fill up, even during the weekend before Christmas?

Rationalitate,

(sorry a small but perhaps relevant parentesis): I don’t know what proponents of a carless society think … but today I’m staying home recovering from the flu. I did however drive briefly to my office 32 miles roundtrip (55 min travel time) to attend an impotrant meeting with my staff. It was difficult, but the thought of walking outside ½ mile to a station waiting and riding a light train, walking another ½ mile to my office and then turning around and doing the reverse seems rather repugnant right now. I don’t think the other passengers on the train would appreciate my pollinating them with viruses either.

It was difficult, but the thought of walking outside ½ mile to a station waiting and riding a light train

What kind of land would you have had to walk through? Commercial land, where often regulations require as much land dedicated to parking lots as to actual buildings? Or residential land, where the vast majority of land is zoned for only single-family detached dwellings? If the land were free of restrictions, might the density be high enough to support more mass transit, cutting down the time you’d have to wait for a train and the time that you’d spend walking to the station? Similarly, might the density be high enough to turn your 55-minute commute into a slow-moving 2-hour commute?

There’s no doubting that mass transit today is absurdly inadequate for our needs. But then again, the market is also absurdly restricted. An indictment of the status quo is nothing more than an indictment of the status quo, and says nothing of what it would be like to commute in a place without market-distorting regulations like zoning laws, mandatory parking laws, roads (and mass transit systems) whose user fees don’t cover the underlying value of the land, etc.

I was actually comparing it to Europe where two ½ mile walks would be rather typical. Comparison came to mind because that is how the attendees we were teleconferencing to in London got to their offices.

Though for what you wrote about lane mile costs here($2.5 million) , I’ve seen track mile costs less than that($1.5 million).

“And furthermore, while a light rail line is relatively self-contained – no one needs to buy anything more than a ticket to use the system – a highway requires a huge amount of parking spaces on people’s property to remain useful (by one estimate – though I can’t remember the source – America has three parking spaces per car).”

A good point but not entirely true. Their is the price of the ticket + taxes paid which in is 30-40% of the federal transit fund today, rigth? A fund filled for by national gas taxes, right? And for many of these LRT projects there is frequently a local component. For example, Fastracks in Denver is funded via a sales tax hike.

As for the parking spaces, I wouldn’t assume that absent current common zoning regulations that the ratio would be that high. I’d also question that figure in terms of how they count parking spaces. Fore example, if the driveway can hold two cars and the garage hold 2 are they counting that as 4? Does that really tell us anything then?

highwayman–> I’m curious, what project cost less than $1.5 million per track mile?

A good point but not entirely true. Their is the price of the ticket + taxes paid which in is 30-40% of the federal transit fund today, rigth? A fund filled for by national gas taxes, right? And for many of these LRT projects there is frequently a local component. For example, Fastracks in Denver is funded via a sales tax hike.

No doubt rail is highly subsidized. (Then again, it’s also sabotaged from the start by zoning laws which reduced density. This is good for a car [high density is incompatible with roads], but bad for mass transit. Same could be said for the entire mortgage industry, which has traditionally been subsidized by the government and which has traditionally promoted low-density development.) But those figures are easy to quantify and the Antiplanner (and many others) have told us about them many times. I wasn’t suggesting that this was false, merely that there are many costs inherent in roads that are not calculated, and indeed are not calculable. Another big one is the value of the land itself, which is a bigger concern for roads than for rail considering roads take up much more space than does rail.

Also, to the Antiplanner: do any of those per track mile/per lane mile include the price of the land beneath it? It would seem to me that if you were building a road/track through populated land (as one is wont to do with transportation), the value of the land would be higher than the labor and materials required to construct it. Eminent domain and the threat of eminent domain would seem to make putting a fair market value on the land an impossible task.

A good point but not entirely true. Their is the price of the ticket + taxes paid which in is 30-40% of the federal transit fund today, rigth? A fund filled for by national gas taxes, right? And for many of these LRT projects there is frequently a local component. For example, Fastracks in Denver is funded via a sales tax hike.

No doubt rail is highly subsidized. (Then again, it’s also sabotaged from the start by zoning laws which reduced density. This is good for a car [high density is incompatible with roads], but bad for mass transit. Same could be said for the entire mortgage industry, which has traditionally been subsidized by the government and which has traditionally promoted low-density development.) But those figures are easy to quantify and the Antiplanner (and many others) have told us about them many times. I wasn’t suggesting that this was false, merely that there are many costs inherent in roads that are not calculated, and indeed are not calculable. Another big one is the value of the land itself, which is a bigger concern for roads than for rail considering roads take up much more space than does rail.

Also, to the Antiplanner: do any of those per track mile/per lane mile include the price of the land beneath it? It would seem to me that if you were building a road/track through populated land (as one is wont to do with transportation), the value of the land would be higher than the labor and materials required to construct it. Eminent domain and the threat of eminent domain would seem to make putting a fair market value on the land an impossible task.

Sorry for the double post, also:

To the Antiplanner: According to the Wikipedia article, light rail in the US costs between $15 and $100 million per track mile, with the average excluding the extreme outlier Seattle being $35 million per track mile. That means $60 million wouldn’t “barely get you one mile,” but rather would almost get you two miles. The article also says that some have been built for less than $20 million per track mile, which would make it cheaper than some highway projects cost per lane mile.

rationalite wrote “with 1.25 parking spaces per apartment bedroom, you’re almost guaranteed to have to devote more land to parking than to building.”

This could be a very significant reson for the dominance of large lot homes in the Houston housing market. If I understand it correctly a two bedroom apartment must be sold with three parking spaces even if the buyer only wants two or one or none. That is a huge market impediment.

How did the planners or regulators arrive at this figure of 1.25? Survey apartment dwellers or simply divide the number cars in Houston by the number of bedrooms. The latter method would result in family car ownership being applied to singles and couples. Or was the number suggested by suburban proprty developers?

The cost of that parking will be much higher than in a subdivision if inner urban land is more expensive or a basement carpark has to be constructed. That parking requirement is a big disincentive to inner urban renewal. Providing a surfeit of parking also means that those apartment owners who chose not to own a car or multiple cars cannot profit by leasing their spare parking space to a neighbour with two cars.

How did the planners or regulators arrive at this figure of 1.25?

Transportation engineers set things like parking stalls per use, and other things here.

DS

“This could be a very significant reson for the dominance of large lot homes in the Houston housing market. If I understand it correctly a two bedroom apartment must be sold with three parking spaces even if the buyer only wants two or one or none. That is a huge market impediment.” — rationalite

Huge? Land around houston’s pretty cheap. And even with the rise in the cost of asphalt parking’s pretty cheap to build and maintain.

1. I didn’t say that, someone else did. (Though I agree with them.)

2. It’s not the accounting cost of parking that’s high, it’s the opportunity cost that’s high. Every piece of asphalt is another piece on which you can’t build, and every missed opportunity to build is a misses opportunity for rent.

3. Requiring as much parking as building puts a 100% premium on the price of any land purchase a developer wants to make. Some of that likely would have been put it anyway, but the extra cost is still pretty high.

“How did the planners or regulators arrive at this figure of 1.25?

Transportation engineers set things like parking stalls per use, and other things here.”

ITE go out and measure parking usage at various locations, which reflect the land use type. So they may, for example, measure the parking levels at an office site, at a certain time of day, for their office parking dataset. Then they draw a graph, where hopefully there is a linear relationship between parking levels and floor area/number employees, etc.

Local authorities, who have to decide on the number of parking spaces often then set their standards equal to the observed levels of parking in the ITE manual. Transport planners also 🙁 sometimes use the numbers uncritically.

This is expensive, and fewer car parking spaces could be specified. The problem really starts when the local authority adds in extra parking just in case. Extra parking induces traffic, which induces extra parking, and when ITE observe this, it ratchets up the parking one more level.

prk166, Land around houston’s pretty cheap. Yes, but what about land in Houston itself? Or more precisely, within the Houston city limits of 25 or 50 years ago.

When I said huge market impediment I meant precisely that. Nobody wants to pay for something they don’t need or want, and more bizzarly people don’t seem to like wasting what they’ve paid for. Sell them more parking spaces than they want and they’ll feel a psychological need to use it. Problem is it’s probably illegal to use it for any purpose other than car parking.

Although my real point wasn’t confined to Houston but is even more apt in older cities or new cities trying to emulate old cities. Once land becomes too expensive to be wasted car parks or single level dwellings then you start looking at tens of thousands of dollars in contruction costs to build something that most of your customers don’t want or need. Need possibly being more important than want when price differential enter into the purchasing equation.

Pingback: Just Let People Do What They Want With Their Own Land » The Antiplanner

Pingback: Who Is the Hypocrite? » The Antiplanner