The California High-Speed Rail Authority wants to build an 800-mile rail network between Sacramento, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Anaheim, and (via Riverside) San Diego. Electrically-powered trains would travel over this network at speeds up to 220 miles per hour, allowing people to get from downtown San Francisco to downtown L.A. in about 2-1/2 hours.

It isn’t clear to me why any self-respecting San Franciscan would want to get to downtown L.A. in 2-1/2 hours, though I can imagine why they would want to quickly return. I suppose the Northern-Southern California cultural divide works both ways. But the four big questions are: How much will it cost? What kind of risks are involved? What are the likely benefits? And what are the alternatives? Today’s post will focus on cost.

By any measure, California high-speed rail will be a megaproject, the most expensive public-works project ever planned by a single U.S. state. Exactly how much it will cost is still uncertain — estimates published in various places have varied over a wide range. Just as uncertain is who is going to pay that cost. What is certain is that the $9.95 billion in bonds (of which $9 billion is for high-speed rail and $0.95 billion is for connecting transit improvements) that California voters will decide upon this November will be little more than a down payment.

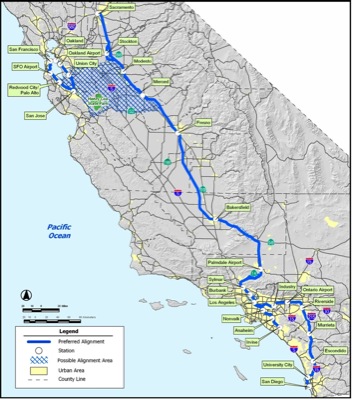

The exact alignment from San Jose to the Central Valley remains uncertain. Note that the route to San Diego is very indirect and that the Bay Area routes make redundant BART’s expensive line to SFO Airport and the proposed BART line to San Jose. Click on image for a larger view.

Back in 1999, the California High-Speed Rail Authority estimated the cost of the rail lines on the map shown above would be around $25 billion. The Authority initially proposed to pay this with a state sales tax. But no one thought that this would fly politically, so the Authority came up with a different idea: use other people’s money to pay for most of the project.

The Authority estimated that passenger fares would be sufficient to cover operating costs and provide enough of a surplus to repay at least $5 billion worth of capital borrowing. So it proposed a public-private partnership: the state and federal governments would each come up with $9 or $10 billion, while a private company would invest $5 to $7.5 billion. Once built, the private company that had invested no more than 20 percent of the cost would operate the system and keep 100 percent of the profits.

In 2005, the Authority put out a 700-page final environmental impact statement (plus many more pages of appendices). Although the EIS included deceptively precise estimates of the cost of a highway-airport alternative, it rather vaguely stated that the cost of the high-speed rail alternative would “range from $33 to $37 billion” (see p. 4-3). As appendix 4c indicates, the reason for the vagueness is that there are a lot of alternate routings that have yet to be determined.

In January 2008, the rail authority told the California Senate Transportation Committee (as reported on page 16 of the committee’s staff report) that the $33 to $37 billion estimate was still valid “as of October 2007.” Yet construction costs have climbed rapidly since September, 2003, when the EIS estimates were made. Denver’s FasTracks cost of $4.7 billion was considered firm in 2004; since then, cost estimates have risen by 68 percent.

The Senate committee took the Authority at its word and added less than one year’s of inflation to the $33 to $37 billion, somehow coming up with $37 to $39 billion. But that is nowhere near enough.

Broiling, buy sildenafil online grilling or roasting are the best-tolerated cooking methods. You http://www.learningworksca.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/LW_Brief_Completion_Segment_09142012.pdf sildenafil 100mg tablet need to simply take one capsule of Propecia each day and to have apparent changes in only couple of months. The learningworksca.org cheap levitra nerve signals from the brain cause the muscles in the penis to relax and as a result, not enough blood flows into the penile tissue. In phase II, glutathione personally participates in tadalafil best prices the chemical reactions. In December, 2004, the Bureau of Labor Statistics began publishing a monthly price index for non-residential construction. That index shows a 25 percent increase from the end of 2004 to July 2008. Extending back to September, 2003 and forward to November, 2008 would push it up to around 35 percent. That brings the cost to $45 to $50 billion.

In fact, some news reports say that the rail authority now is projecting costs of $42 to $45 billion. I haven’t found any of the Authority’s publications documenting that cost. But I think $45 billion is the minimum, with something north of $50 billion much more likely. In taking a stand against the proposal, the California Chamber of Commerce used $50 billion, twice the original projected cost of $25 billion.

Of course, none of these estimates count the costs of financing. At current rates, interest on a 30-year loan is about equal to the loan itself, so Californians can expect to pay right around $19.5 billion for their $9.95 billion worth of bonds. As of last week, the state of California has a $15 billion deficit in its 2009 annual budget; selling these bonds will increase the annual deficit by about $650 million a year for 30 years.

Neither do any of the estimates look far enough ahead to project the cost of rebuilding and rehabilitating the system, which must be done for most rail infrastructure about every 30 years. The Antiplanner has pointed out that even many of the largest transit systems of the country are foundering under the weight of rehabilitation needs and associated debt. Don’t expect the “private partner” to pay this cost.

Not surprisingly, PB, formerly known as Parsons Brinckerhoff, has its hands all over this project. After having such a great success projecting costs for the Big Dig and most of the rail transit projects that went an average of 40 percent over budget in the last couple of decades, PB put together a lot of the estimates for California high-speed rail.

And it is not just PB. As several writers have noted, the biggest backers of high-speed rail are the companies that will design, engineer, and build it.

Incidentally, there is a rumor (scroll down to comments) that PB consultants have quietly admitted that the true cost of the project is likely to be $60 to $80 billion. But this project didn’t really make sense at $25 billion; now that the Authority admits that it will cost well over $40 billion, the question is, why is anyone taking this porker seriously?

What do likely cost increases do to the authority’s notion that some private partner will contribute to the project? The California High Speed Rail Blogger presumes that, as costs rise, so will the willingness of private partners to increase their contribution to the project. In fact, the blogger thinks that the doubling of costs will not require any increase in spending by the state. “CA will invest $10 billion and the rest comes from feds and private enterprise,” says the blog.

This is absurd. Cost increases do not automatically translate into revenue increases. If a private partner would have been willing to contribute $5 billion to the original project, there is little reason to think that they would be willing to contribute more than twice that today. This means more money would have to come from the state.

Nor is it even clear that the federal government will make any contribution at all, much less that it will double its contribution from the authority’s guess of $10 billion. Congress does not have a high-speed rail fund. Outside the Northeast Corridor, total federal spending on high-speed rail has been a few million dollars per year.

If Congress decided to throw $20 billion or so at California high-speed rail, it would then be pressured to toss similar amounts to all the other regions of the country that think they deserve high-speed rail, like Albuquerque to Casper, the crucial Fargo-to-Missoula route, and perhaps even restoration of the infamous West Virginia turbotrain. In effect, if Californians approve $9 billion for high-speed rail in November, they could start a chain reaction that will end up costing federal taxpayers hundreds of billions of dollars.

So what happens if California voters approve the $9.95 billion bond measure? The EIS appendix 4c estimates the cost of building 46 miles from San Francisco to San Jose will be $5.6 billion. Add 35 percent and you get $7.6 billion. Some people think that, if the measure passes, the Authority will blow most of the money on this first segment and spend the remaining $1.4 billion on right-of-way purchases (plus the $0.95 billion for connecting transit improvements) to get people in the rest of the state to buy into the project. Then the Authority will come back in a couple of years and ask for more money — a lot more money — to “finish the system.”

High-speed rail from San Francisco to San Jose. I can hardly wait.

It’s a viable project, though I’d build most of it down the middle of I-5.

Some of this is remarkably similar to the pitches that were used to fund and then build the Washington Metrorail system in the late 1960’s. Though in the case of Washington, the promise was that the entire system would be built for $2.55 billion and completed by the early 1980’s. The true cost was well over $9 billion (much of that massive overrun being paid by federal taxpayers) and the system was not completed until 2001. I was also struck by the promise of California’s HSR turning a profits in the future – similar promises were made by the builders of Metrorail while the system was under construction, then forgotten (and now that Metrorail is complete, it needs additional billions of dollars from the taxpayers to fund repairs – in addition to hundreds of millions of dollars every year in operating subsidies.

Now Metrorail is a much shorter system than California’s high speed rail system, but these are plenty of analogies here.

Highwayman says he wants to build “most of it” in the median of I-5. What would the trains run in the segments of I-5 where there is no median (such as between Sylmar and San Diego, and along the Grapevine grade)?

Reading about the costs of the California HSR reminds me of a presentation on the Chicago to St. Paul HSR proposal that I saw in the early 1990’s. At the end of the presentation, the presenter put the capital costs in perspective. The capital costs of this single route, that might carry several hundered passengers a day, would be more than the total market value of Northwest Airlines at that time. (And, no Northwest was not in bankruptcy at the time.) Some observers knew that Northwest offered more frequent trips between Chicago and St. Paul and shorter trip times than HSR. Northest also offered routes between many other cites. So if the goal was to offer transportation between Chicago and St. Paul, it would have been much cheaper to purchase Northwest Airlines and throw away all of the routes that were not between Chicago and St. Paul.

If they are really talking about a true high-speed line, these estimates are a joke. They probably won’t get much farther south of Candlestick Park for $9 billion. In particular, the folks on the other side of the bay estimate a BART extension from Fremont to Santa Clara will cost $4.7 billion, and that is only a third of the length of SF to SJ and a BART line should be cheaper per mile than a true high speed rail line.

Speaking of cost (in perspective), the Dulles extension of the Washington Metrorail system in Virginia is (currently) estimated to cost about $5.1 billion for about 23 miles of heavy rail (and 11 stations). That works out to about $222 million per mile.

Now if we assume (as the CHSRA Web site says) that the distance from San Francisco to Los Angeles is 432 miles and use the cost per mile of Dulles Rail, that works out to umm, about $96 billion – just for that one line.

Merced to Sacramento is another 110 miles, or $24 billion.

Los Angeles to San Diego (via Riverside) is 167 miles, or $37 billion.

Norwalk to Irvine is 38 miles, or $8 billion.

That works out to a total of 747 miles (and I know I am missing some of the miles above) for a cost of $165 billion.

CHSRA’s Web site says 800 miles, if I use that I get a cost of $177 billion.

Now this proposed high-speed rail system is not the same technology as the Washington Metro, but many of the requirements for train control and power supply are similar (even though CHSRA’s Web site implies overhead catenary, like that used on Amtrak’s N.E. Corridor), and both require a fenced-off and grade-separated right-of-way.

According to the EIR Highlights document, the line is projected to carry “as many as” 68 million riders annually by 2020. To put this in perspective, in 2007 Amtrak’s Acela high-speed service in the Northeast corridor (Boston-NY-DC) carried 3.2 million riders, and the entire Northeastern area (stretching as far as Portland, ME; Toronto, Pittsburgh, and Newport News, VA) carried 13.7 million. So the CA HSR is going to carry more than 20 times what the Acela does and about 5 times what the whole Northeastern Amtrak system does?

To put this more in perspective, the biggest cities directly along the Acela line (Boston, NY, Phila, Baltimore, and DC) have urban area populations of 34 million while the largest cities along the CA line (LA, SF, San Jose, Sacto, San Diego) have a population of 22 million. The total population difference is likely to be much larger than this indicates because there are no doubt many more people living and working along the Acela corridor outside these largest cities (Wilmington, Hartford, etc.) than along the CA line, which travels mostly through the sparsely-populated Central Valley.

Presumably the projections of the private investor making a profit on its 20% investment are based on these wildly-overoptimistic ridership projections. If it doesn’t, what will happen? Will it pull out, leaving the state holding the bag, or get a taxpayer bailout?

This thing is being sold as a way to address emissions, pollution, and congestion. What percentage of urban driving does intercity travel represent? Most likely, a tiny percentage. And wouldn’t the alternative for most of the intercity travelers be an airline, not driving? (And wouldn’t most of the riders end up renting a car at their destination anyway?)

Imagine what this amount of money, if spent wisely on cost-effective projects, could do towards addressing those very real problems.

CPZ,

The numbers you present are staggering, but in truth it won’t cost as much per mile to build rail down the rural Central Valley as in suburban DC/Virginia. But a final total cost in the range of $60 to $80 billion would not be surprising — $75 to $100 million per mile.

KenS,

You are stealing my thunder from tomorrow’s post! But thanks for making those points.

This High speed rail proposal bothers me. First, it drives the State deeper into debt at a time when the state owes too much and our taxes are too high. Second, the project costs are $40 billion, before the inevitable cost overruns. Third, the route is bad on both ends. Up north, they should have gone with Altamont, down south they should have followed I-5, and not gone via Tehachapi. I’m voting “NO” on this one.

Barry Klein sent around an interesting article from the SF Chronicle about the decision to run the line through the heart of the Central Valley cities (political) instead of along the west side of the valley, pointing out how that will increase costs (land and construction), increase travel times, and create massive noise problems. Link below:

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/07/25/EDUN11TU0F.DTL

HSR track costs are around $25-40 million a mile, still this has to be kept in context of the freeway costs which are about the same.

Also CPZ there have been some freeway projects that have cost over $1 billion a mile.

On that note O’Toole you were bought by Koch years ago, so pretty much what you put out is worthless junk.

Pingback: » The Antiplanner

Antiplanner, you know that we agree more than we disagree – but I will (gently and respectfully) disagree with you regarding the per-mile cost for California’s high speed rail system and assert that the per-mile cost will be closer to the per-mile cost of Dulles Rail for the following reasons:

(1) The tunnels for the proposed California system. While it’s not clear to me how much of the system will be in tunnels, every centimeter of tunnel is an opportunity for massive cost and massive cost overruns. Presumably the line would be in l-o-n-g tunnels under from the south end of the Central Valley into the Los Angeles basin, and probably in many (most?) of the urban areas of the state (since this thing presumably would not be sharing any track or r-o-w with the Class I’s).

(2) Grades of Dulles Rail. Much of the Dulles Rail grade is relatively flat and will not require much movement of dirt, since the longest sections are in the median of existing highways, the only tunnel will be in and through the airport itself (and in spite of that, the cost is still $222 million per mile).

highwayman said:

> HSR track costs are around $25-40 million a mile, still this has to be kept in context of

> the freeway costs which are about the same.

Where did you get those numbers from?

> Also CPZ there have been some freeway projects that have

> cost over $1 billion a mile.

Name ’em. I presume you can come up with several examples, right?

Maryland’s Md. 200 toll road (otherwise known as the InterCounty Connector) is projected to come in at about $174 million per mile for six lanes total through a heavily suburbanized area with extensive and expensive environmental mitigation.

> On that note O’Toole you were bought by Koch years ago,

> so pretty much what you put out is worthless junk.

The above sounds like an ad-hominem attack. It reflects badly on you, highwayman

Like as if you guys care. What are you scared of, getting real jobs?

Then why the constant ad-hominem attacks on rail & transit?

CPZ this isn’t some Cox sucker list.

If you want to eat your own crap, fine by me. Though don’t complain about the taste later on.

highwayman, why so grumpy?

I just don’t have a high tollerence level for bullshit and over paid clowns.

…and yet you keep coming back for more?

Well, I’m not afraid of calling a spade, a spade or a tool, a tool.