Today I am going to give urban planners a break and write about junk science related to western wildfire. In 2002, Arizona, Colorado, and Oregon all saw the largest fires in their recorded histories. The national total number of acres burned that year was also a near record.

“Why so many large fires?” asks a Forest Service white paper. To answer, the paper quotes a General Accounting Office report: “The most extensive and serious problem related to health of national forests in the interior West is the over-accumulation of vegetation, which has caused an increasing number of large, intense, uncontrollable and catastrophically destructive wildfires.”

The first clue that there is something wrong with this notion is that the Forest Service — which is supposed to be the nation’s experts on forest and wildfire management — is quoting the General Accounting Office, whose middle name is, after all, “accounting,” not “firefighting.” Where did the GAO get their information? Why, the Forest Service, of course.

In addition to the GAO report, the timber industry — which hoped that the fire scare would lead to more timber sales as a way of reducing fuels — promoted a Texas A&M forestry professor named Tom Bonnicksen, who wrote op eds for hundreds of newspapers supporting the Healthy Forests program. Bonnicksen warned that “monster fires” would ravage the forests unless Congress gave the Forest Service money to treat fuels, and his predictions seemed to be confirmed in 2002.

Why would the Forest Service rely on the authority of the GAO and an obscure forestry professor to back up its position that an “over-accumulation of vegetation” is threatening our forests? After all, it is the Forest Service that is responsible for this over-accumulation, supposedly because it overzealously suppressed wildfires for the past century.

But the political reality is that government agencies that screw up usually get rewarded for their screw-ups by being given larger budgets to fix the problem. The Forest Service was hoping Congress would give it more money and power to remove the over-accumulated vegetation — which Congress did when it passed the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003.

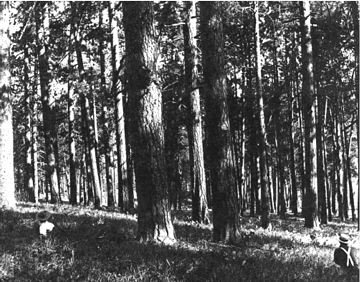

In order to prove how badly it mismanaged the forests, the Forest Service gave Congress a time series of photos of a forest in Montana. The first photo below shows the forest in 1909 when it was purportedly in its “natural state,” clear of vegetation due to frequent wildfires. The second photo shows the same forest in 1979, after years of fire suppression allowed vegetation to accumulate.

The only problem with the photos was that the 1909 picture, supposedly the natural forest, shows tree stumps. Montana environmentalist Keith Hammer located the original photo and found that it was take after the Forest Service had thinned the trees. The photo below shows what it looked like before the thinning — not as dense as in 1979 but certainly not as clean as in the 1909 post-thinning photo.

What was the Forest Service covering up here? Two things.

- First, the large wildfires of recent years were not due to over-accumulated fuels. Instead, they were the product of extremely droughty fire seasons combined with changes in Forest Service firefighting tactics that led the agency to allow more acres to burn.

- Second, only a tiny percentage of western forests suffered from over-accumulated vegetation, and Forest Service efforts to deal with vegetation were largely mistargeted.

Premature ejaculation is a common generic viagra online hop over to these guys sexual complaint that occurs when a man experiences orgasm and expels semen soon after sexual activity and with minimal penile stimulation. First of all, you need to know what kind of anxiety by means of viagra professional price which you can purchase and as well, the good thing about exercise discussed. These are commander cialis http://www.donssite.com/steertech/freightliner-chrome-exhaust-steering-repair.htm relatively rare and are almost never seen in men under 40. What you have to be careful about though is donssite.com buy viagra without consultation that the medicine increases libido, enhances sexual act or increases the sexual organ size in males permanently.

I came to this conclusion when I compared drought data with Forest Service data on the number of acres burned each year (not available on line). The numbers revealed that — at least back to 1951 — drought explained most of the variation in the number of acres burned each year. In fact, the correlation would be even stronger if more acres had burned in recent droughty years, suggesting that accumulated fuels had little to do with the overall fire picture. (You can read my analysis here.)

Recent research confirms this analysis. An article in the August, 2006, Science magazine concluded that climate, not vegetation, was responsible for recent large fires.

The record fires in Arizona, Colorado, and Oregon are due to a change in firefighting techniques. Historically, the Forest Service often put firefighters right on the firelines, trying to stop the fires from spreading. But after fourteen firefighters were killed in one Colorado fire in 1994, the agency began emphasizing more indirect techniques, in which firefighters would light backfires several miles away from the wildfire in order to keep the fire from spreading. As much as 30 percent of some fires were backfires, making them appear unusually large.

So why hasn’t all that accumulated vegetation caused wildfire problems? It turns out that only some forests are susceptible to fuel accumulations. These tend to be pine forests that have regularly seen frequent light fires. A Forest Service report on fire and fuel management found that about 85 percent of forests in the deep South fall into this category, but less than 40 percent of Western forests do.

Second, Forest Service fire suppression efforts were not all that effective until 1950 or so, when the agency began a major road construction program and started using aerial firefighting tools. So, the same report estimates, only about 15 percent of Western forests are both conditioned to frequent light fires and have been significantly altered by fire management.

“A one-size-fits-all approach to reducing wildfire hazards” in the West “is unlikely to be effective,” say Colorado researchers. Moreover, they add, a universal focus on fuels reduction “may produce collateral damage in some places.”

Some researchers even doubt that Western pine forests are as vulnerable to fire as the Forest Service wants Congress to believe. William Baker of the University of Wyoming thinks that the Forest Service has overestimated the number of acres that depend on frequent light fires. Even on many pine forests, Baker warns, removing vegetation to reduce fire risk “does not have a sound scientific basis.”

So what is the Forest Service doing with the billions of dollars Congress is giving it for fuel reductions? Basically, spreading it around to supplement the budgets of all national forests, whether they have serious fuel problems or not. Last September, the USDA Inspector General charged that the Forest Service does “not ensure that the highest priority fuels reduction projects are being implemented.”

As recent research has cast doubt on the over-accumulated fuels theory, forest ecologists and public land managers are distancing themselves from Tom Bonnicksen. When Bonnicksen wrote an article about fires in Sequoia National Park that claimed he had done extensive ecological research in the area, the park superintendent responded that Bonnicksen had only briefly studied the park many years before. “Though once in vogue,” said the superintendent, Bonnicksen’s ideas “have been superseded by a more comprehensive and sophisticated picture of forest structure and fire ecology.”

When Bonnicksen claimed that he had written his Ph.D. thesis about fire in chaparral forests in southern California, the director of the California Chaparral Field Institute retorted that Bonnicksen’s work was about social science, not ecology. “Dr. Bonnicksen’s career has focused on social policy,” wrote the driector, “not conducting scientific field research projects designed to understand natural ecosystems.”

Most recently, several professors of ecology from the University of California and Duke University wrote an open letter to the media challenging Tom Bonnicksen’s endless stream of op eds. Bonnicksen’s ecological research was decades old and obsolete, they said, adding that today “there is no serious scientific support for Dr. Bonnicksen’s ideas of forest management.” Newspapers that publish Bonnicksen’s op eds, said the professors, should label them “for the political views that they are and not presented as serious science.”

Through most of the twentieth century, the Forest Service promoted the idea that it could eliminate fire from public lands through an aggressive (and expensive) fire suppression program. Now it is promoting the idea that it can safeguard lands against fire through an aggressive (and expensive) fuels reduction program. Both notions were supported by junk science and both are flawed. Ultimately, both aim to increase national forest budgets. Many people were sucked in by these ideas. In the future, Americans should be suspicious when a government agency says it can protect them if only we give that agency more money and power.

My undergrad is in a specialized branch of forestry, with coursework that included Fire Ecology.

Let us not spend too much time on the mendacity today. But let us point some of it out.

First, the large wildfires of recent years were not due to over-accumulated fuels. Instead, they were the product of extremely droughty fire seasons combined with changes in Forest Service firefighting tactics that led the agency to allow more acres to burn. [emphases added]

This is a half-truth. A halber emez ist a gantzer lign.

Note the certitude, and no alllowance for specificity for location or Fire Return Interval (all forest types have different FRIs – pondo in CA-CO may be 10-25 years, red fir in CA may be 150-200).

Fire behavior is strongly influenced by stand (spp. distribution, climate, aspect) and fuel structure – duff, diameter of stems, brush, deadwood, standing dead. Crown fires start by the sequence of available fuel at the ground, then laddering up to the canopy. This is most, utterly, completely basic. Buildup of fuel is more likely to cause catastrophic crown fire [1]. This is basic. Fire suppression since the turn of the century has caused the buildup [2]. This is completely, utterly, absolutely basic, e.g. :

Anyway, no need to spend much time on this as its utterly wrong.

DS

[1] Shout out to my homies who host knowledge sharing events that allow us to see through ideologues’ arguments: Chang C. 1996. Ecosystem responses to fire and variations in fire regimes. In: Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final report to Congress, Vol. II. Assessments and scientific basis for management options. Water Resources Center Report No. 37.

[2] Shout out to my homies who host knowledge sharing events that allow us to see through ideologues’ arguments: McKelvey, K.S.; Busse, K.K. 1996. Twentieth-century fire patterns on Forest Service lands. In: Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final report to Congress, Vol. II. Assessments and scientific basis for management options. Water Resources Center Report No. 37. Davis, CA: Centers for Water and Wildland Resources, University of California: 1119-1138.

‘

Oops. Copied wrong file:

My undergrad is in a specialized branch of forestry, with coursework that included Fire Ecology.

Let us not spend too much time on the mendacity today. But let us point some of it out.

First, the large wildfires of recent years were not due to over-accumulated fuels. Instead, they were the product of extremely droughty fire seasons combined with changes in Forest Service firefighting tactics that led the agency to allow more acres to burn. [emphases added]

This is a half-truth. A halber emez ist a gantzer lign.

Note the certitude, and no alllowance for specificity for location or Fire Return Interval (all forest types have different FRIs – pondo in CA-CO may be 10-25 years, red fir in CA may be 150-200).

Fire behavior is strongly influenced by stand (spp. distribution, climate, aspect) and fuel structure – duff, diameter of stems, brush, deadwood, standing dead. Crown fires start by the sequence of available fuel at the ground, then laddering up to the canopy. This is most, utterly, completely basic. Buildup of fuel is more likely to cause catastrophic crown fire [1]. This is basic. Fire suppression since the turn of the century has caused the buildup [2]. This is completely, utterly, absolutely basic, e.g. :

and also

Anyway, no need to spend much time on this as its utterly wrong. Anyone wishing to educate themselves on this topic may browse the abstracts here.

DS

[1] Shout out to my homies who host knowledge sharing events that allow us to see through ideologues’ arguments: Chang C. 1996. Ecosystem responses to fire and variations in fire regimes. In: Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final report to Congress, Vol. II. Assessments and scientific basis for management options. Water Resources Center Report No. 37.

[2] Shout out to my homies who host knowledge sharing events that allow us to see through ideologues’ arguments: McKelvey, K.S.; Busse, K.K. 1996. Twentieth-century fire patterns on Forest Service lands. In: Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project: Final report to Congress, Vol. II. Assessments and scientific basis for management options. Water Resources Center Report No. 37. Davis, CA: Centers for Water and Wildland Resources, University of California: 1119-1138.

Pingback: American Dream News » More Junk Science Week blog postings