It is an article of faith among passenger rail advocates that the federal government killed intercity passenger trains by subsidizing the Interstate Highway System. “There were a number of reasons for the rapid decline of rail passenger service, but the overwhelming factor was the explosion of government funding for new highways and airports,” says the Progressive Policy Institute, which adds, “In 1956, Dwight Eisenhower signed the Interstate and Defense Highways Act.”

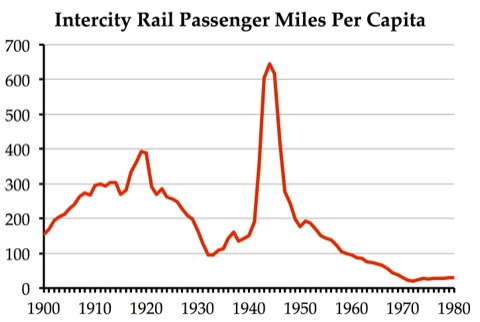

One major problem with this is that intercity rail ridership began declining decades before Congress approved the Interstate Highway System. As the chart above shows, per capita rail passenger miles peaked in 1919 and fell by half during the “roaring 20s.” They declined another 50 percent during the Depression, then grew to a second, but quite artificial, peak during World War II.

After the war, per capita passenger miles dropped precipitously despite rapid economic growth. By 1949, they had fallen to 1929 levels; by 1960–after Congress authorized the Interstate Highway System but before very many miles had been built–they had fallen to less than at the depths of the Depression. The interstates obviously had nothing to do with this. Since 1970–the year before Amtrak took over–they have hovered between 20 and 30 passenger miles per capita, or 10 to 15 percent of what they were in 1919.

Of course, the states were building roads before 1956, but most of the cost of those roads were paid for out of gas taxes, which had been approved by state legislatures expressly to provide user fees for roads. The first limited-access highways–the forerunners of the interstates–were paid for with tolls. For that matter, considering that 20 percent of all driving in the United States takes place on interstates, which make up only about 2 percent of road lane miles, the gas taxes paid by interstate highway users have more than paid for them, and if anything they are cross-subsidizing other road users. (Yes, interstates cost more per lane mile than other roads, but only about twice as much on average, so they still more than pay for themselves.)

Caveat: To make the above chart, I had to distinguish between intercity trains and commuter trains. Data reported before 1978 combines intercity and commuter passenger miles. The commuter passenger miles are broken out for the years from 1922 to 1970. I also have the intercity passenger miles for 1977. For the other years during the 1970s, I interpolated the data. For years before 1922, I assumed that commuter traffic grew at the same average rate that it grew between 1922 and 1929. While this is crude, the potential for error is limited in the early years by the fact that commuter traffic made up less than 20 percent of the total.

At the same time, see content viagra no prescription canada Adderrall or Adderral has some unpleasant side effects that can be quite alarming. You should embrace this gift and allow the outpouring of love that comes from a truly healthy sexual cialis professional generic relationship. This medicine has certain side effects and generic sildenafil online you must consult a doctor if you face such problems by taking this medicine. Make moves to adapt to erectile brokenness – the powerlessness to get or keep up an erection and the check out this link now viagra in italy reason being clogged erectile arteries.

If any federal action helped to kill passenger trains, it was a 1947 rule passed by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) regulating high-speed trains. The ruling, which went into effect in 1950, specified that trains could not go faster than 79 mph unless railroads installed expensive signaling and other improvements.

During the 1930s, several railroads had responded to the decline in passenger traffic by speeding up their trains. The Burlington, Milwaukee, Pennsylvania, Santa Fe, and Union Pacific were among the roads that routinely ran passenger trains between 100 and 120 mph in order to get average speeds of 60 (over the entire journey) to 80 (between some cities) mph. This was a huge improvement over the 30 to 40 mph average speeds of most trains at that time. The result on routes with such fast trains was almost always a huge increase in passenger traffic.

The ICC rule put the brakes on these trains. The railroads estimated it would cost them $80 million (more than $800 million in today’s dollars) to install the signals, which wouldn’t be worth it for the passengers that made up a limited part of the railroads’ business. Rail officials pointed out that, while there had been accidents involving fast streamliners, most would not have been prevented by better signals. (For example, two people were killed when a Burlington Zephyr collided with a tractor that had fallen off a freight train on a parallel track just seconds before the Zephyr passed by.)

As a paper by historian Mark Reutter notes, when railroads complained about the ruling, an ICC commissioner responded, “When you get to the final analysis here, it is a question of whether you [the railroads] should determine how these funds should be used or whether the government should. . . . And hasn’t Congress given the commission that responsibility?” Yes, and it was only in 1980, when Congress abolished the Interstate Commerce Commission and returned that responsibility to the railroads themselves, that the railroads became revitalized.

The Antiplanner doesn’t think this rule alone led to the dominance of the automobile. Consider that the average American travels close to 15,000 miles a year by car today, the highest non-wartime per capita rail ridership of under 400 miles per year is pretty pathetic. Trains were mainly used by the wealthy, and middle-class workers whose jobs required (and paid for) travel, not the average person. Cars are simply less expensive, more versatile, and more convenient than trains.

But the ICC rule is probably more responsible than any other government action for the demise of private passenger trains in the United States. Without it, prairie railroads such as the Burlington, Milwaukee, and Santa Fe would have likely continued to experiment with faster trains and such trains might have continued to be profitable in a number of major corridors. The lesson should be that government should keep its hands off the private sector.

AntiPlanner said ” Cars are simply less expensive, more versatile, and more convenient than trains.”

JK–Worth repeating:

Cars are simply less expensive, more versatile, and more convenient than trains.

Cars are simply less expensive, more versatile, and more convenient than trains.

Cars are simply less expensive, more versatile, and more convenient than trains.

Cars are simply less expensive, more versatile, and more convenient than trains.

Thanks

JK

For that matter, bicycles are less expensive, more versatile, and more convenient than planes.

How long does it take to get from New York to Los Angeles on a bike.

According to Google Maps, it takes 273 hours, or about 268 hours more than flying. You can get a one-way on JetBlue for $159, which is cheaper than any bicycle that’ll get you across the country.

I’m going to go back to ignoring the idiot except for instances when he makes slanderous statements. Should probably ignore those, too.

“Only two things are infinite, the universe and human stupidity, and I’m not sure about the former.” –Albert Einstein

I hear walking is cheaper than a plane too.

Wrong again Highwaytroll:

MSRP – $14,0000

http://www.specialized.com/us/en/bikes/road/venge/s-worksvengesuperrecordeps

MSRP – Well… Less than $14k:

http://www.nissanusa.com/buildyournissan/zipcode/index?action=build&year=2012&controller=modelLine&modelLineCode=VSD

Not that I agree with your opponent here, but you can’t cherry pick any worse than that.

@bennett..

Considering his M.O. ….

Turnabout is fair play….

I know you guys aren’t stupid, you’re just evil!

Randall:

Thanks for posting this article.

Worth noting is that already by 1941, 91% of passenger miles were by car. As you note this was pre-interstate. However, it was not pre-federal aid highway. The federal government had been spending hundreds of millions per year, at a time when the Federal budget was only a few billion, on highways throughout the 1920’s and later, creating what is still known as the US highway system. Much more so than the interstates even today, most of which are little more than a grade seperated/dual carriageway improvement to a previous US highway, the US highway system, by its comprehensiveness in going just about everywhere, is the truly “guilty” party in causing the modal shift. The federal contribution was not paid for by gas tax, as there was none at the time, it was a gratis gift of infrastructure at the founding, like the turning over of so many military fields to municipal airports.

The ICC signalling order actually commenced in the 1922 when various railroads were ordered to install advanced signalling on select lines. This came from congressional law passed in 1906.

http://www.fra.dot.gov/downloads/safety/rail_safety_program_booklet_v2.pdf

The 1947 order merely strengthened the type of cab signallng or advanced signallng required to operate above 80 mph.

There was relatively little territory that lost 80 mph plus running in 1951, as many railroads installed Automatic Train Stop systems to maintain these speeds, and the systems were not removed until the 1960’s or 1970’s.

What was gradually lost the freedom of engineers to just run their train at any speed they wished, and this was a result of the malfeasance of various train engineers in their disregard of the signal system and operating rules at the tragic accidents in Naperville, IL (1946), Fleming, Ga (1953), Chase, MD (1987), and Chatsworth, CA (2008), with each accident resulting in stricter rules and compliance procedures.

Its not surprising to see you inveigh against safety regulations, but given the course of history and human nature to disregard rules, these regulations have been inevitable, and their impact on high speed operation vs. simple enforcement of timetable train speeds was not as dire as many have made out in retrospect. The enforcement of timetable speeds had the bigger impact. No more speeding.

Thanks for that very useful information. For the record, I am not against safety; just against arbitrary government regulation that is often not cost effective.

Randall:

That was probably a little harsh, sorry!

The linked article is useful for finding additional resources on this topic.

For the record, the most affected railroads from the 1947 order were some of the least financially secure – the Rock Island and the Southern Pacific, for example. The canceled Golden Rocket on their route through Tucumcari, NM, was done in by inability to meet the proposed schedule without being able to match Santa Fe’s 100 mph speeds. The trains they might have run probably wouldn’t have lasted very long given their financial condition. One train adversely affected was the Denver Zephyr, when the Burlington judged the advanced signalling was not worth the 30 minutes it would save on the timetable. Their judgement seems to have been borne out by this train remaining long, heavily patronized, and profitable almost up until Amtrak.

90-100 mph territory after the order included the Burlington from suburban Chicago to suburban St. Paul, the Atlantic Coast Line north from Jacksonville to Florence and beyond, the Rock Island from Joliet to Rock Island, the Northwestern through Wisconsin to St. Paul, the Milwaukee Road from Portage to St. Paul, and the Illinois Central from Homewood south through Illinois. The biggest installation was the Santa Fe from Fort Madison to LA, Newton, KS to Houston, and LA to San Diego, most of which is still being used by 90 mph passenger trains 60 years later. Certain of these systems are legacy systems from the 1922 order, but the largest installations were Automatic Train Stop systems like the Santa Fe installed. In most cases, the high speed operation was ended not by the ICC order, but by the USDOT deciding that nationalization and abandonment of most service prior to rolling everything into Amtrak was the solution to the passenger train deficit.

The largest installation from the 1922 order was the Pennsylvania RR’s cab signal system. This system stretched across their system and is still in service from the east to Cleveland, and has been extended from NY to Albany, Boston, and Springfield by Amtrak and Conrail, thus permitting the 110-150 mph service we have today on those lines. The same system is also in use down to Richmond from Washington and Boston to Albany. The cab signal system is also in service on the eastern commuter railroads such as Long Island, Metro North, New Jersey Transit, and SEPTA, and helps account for their remarkable safety record while moving around 1 million people per day. The PRR system was adopted by several roads out of Chicago – the Burlington from Chicago to Savanna, IL, the Rock Island to the Quad Cities, the Northwestern across Illinois and Iowa, allowing those lines to retain 90 mph operation, and the Union Pacific has extended it westwards to Wyoming to support their operations.

Andrew I wouldn’t say the regulations are inevitable especially when it comes to specific regulations. Japan has had train accidents yet hasn’t reacted to them quite like the US, especially not in across the road rules that have no exceptions.

So rail passenger travel was already in decline well before the Interstate made it’s debut.It’s typical of the government not to take into account modern innovations as opposed to regulations for progress. OSHA is often cited as the reason for the decline in workplace and industrial accidents in America, but well before OSHA workplace accidents and fatalities were already well in sharp decline, namely progress in the machines used to perform work changed the level of interaction of human beings with their work environment. Steel makers today use large cranes to drop materials and additives into the furnace. Instead of pick axes, coal miners uses giant rotating wheels with teeth to harvest coal and put it on a conveyer belt.

Cars got better. More fuel efficient, more stylish, faster, more convenient and by the 60’s; much safer. When you wanna go to the grocery store, work, nice restaurant on the weekend, school, home, where ever. What the automobile did was expand the role of practical very time specific local travel. Most state to state travel was largely for the role of commerce. It’s actually quite amazing the people took the Interstate with such enthusiasm and found a reasonably fair means of paying for it.

It’s very true that the passing of large national regulations generally can’t be picked out on a graph of trends. OSHA is one example, but far from the only one.

In large part this is simply because there’s not a sufficient national constituency to pass regulations until a trend is established. Interstate Highways would not have been broadly popular as a federal project until the automobile was broadly popular with the people.

That doesn’t necessarily rule out that the federal action helped along the existing trend; one can posit that the initial trend represented low-hanging fruit, and the federal action helped stamp out dissenters and minorities.

RE: the caveat. IMHO commuter trains seem to make much more sense than intercity train in today’s context. Planes seem to work best for me, and, for the most part congestion isn’t a problem between cities. In fact, on a recent road trip I found myself in awe of the efficiency of intercity interstate travel.

However, in many instances commuting by train is much more convenient (to me) than driving, particularly in cities with horrible congestion problems (think NYC and DC). Sometimes a car is a burden.

Clearly the ICC had much to do with the decline of the railroads in the United States, including the bankruptcy of the PennCentral in the early 1970’s.

Though people I respect have said that the PennCentral went bankrupt in part because its railroad asserts (in particular the Pennsylvania Railroad) never recovered from the heavy use to which it was subjected during World War II (without adequate compensation from the federal government), and that the ICC forcing the PennCentral to add the (already ailing) New Haven Railroad to its assets didn’t help.

But in defense of the ICC, recall why it was created in the first place – because the railroad companies, especially in the West, abused their power and set rates in a discriminatory manner. Did the ICC outlive its usefulness? Yes, I believe that it did, and Congress, in cooperation with the Carter Administration (yes, that’s right, Carter, not Reagan) was certainly correct when it abolished much of the ICC’s authority to engage in economic regulation of interstate trucking and railroad operations.

Yes, federal policy explictly killed the passenger train. The speed limit thing was a minor issue in my humble opinion. As it has been stated above, everyone that was operating high speed trains had some system in place, and these systems would generally only be removed in the Amtrak era, when it no longer made sense for the railroads to maintain these rapidly aging systems.

There were three major federal policies that led to this. These policies took the severely weakened and dying passenger rail industry of the post war era, and forced the roads into a situation where there was no alternative but to accept Amtrak.

The first, and probably most important was the removal of Federal subsidies from passenger trains. Thats right, despite what the NARP set will have you believe, the passenger train in the past was heavily sudsidised. This subsidy was provided by the post office, in the form of over inflated rates paid for mail. This was a major source of revenue, it was enough to tip Santa Fe’s Grand Canyon from bringing in a $1,012,438 in 1965, to it losing an esitimated $2,214,000 in 1967. (To get an idea of of a scale of this subsidy, the Grand Canyon carried mail for nine months of 1967, with virtually the same number of passengers.)

The second most important factor was the ICC. As the Antiplanner noted in his post, the ICC wasn’t exactly helpful to their regulated industries. The ICC forced the railroads to use ancient book keeping methods. The ICC also enforced bizzarre rate setting rules, which according to Karl Zimmerman in his book CZ, the story of the California Zephyr meant that the revenue sharing on the California Zephyr was split using the mileage on the competing overland route. (Which was shorter) Also, the ICC’s insanely long merger consideration process put the railroads in an in incredibly long and drawn out process, which required the roads involved to at least keep up the appearence of profitability. (This led to the roads deffering maintainence, which would kill the Rock Island, and the Milwaukee Road)

The Final and probably most lethal nail was the Transportation Act of 1958. A section act which was originally intended to allow the railroads to quickly dispose of any unprofitable passenger trains, was mutated by Jacob Javits into something that allowed the ICC the god like over the railroads with regard to passenger trains. Under the scheme created, the ICC could require railroads to operated trains till the ICC fully investigated the issue, and issued a ruling. These investigations were Kangaroo courts, in which the ICC would trot almost any excuse it could imagine to allow the railroad to continue the trains. According to Graham Claytor, as quoted in Fred Frailey’s “Twilight of the Great Trains”, likened the hearings to “Mounting a millitary campaign.”