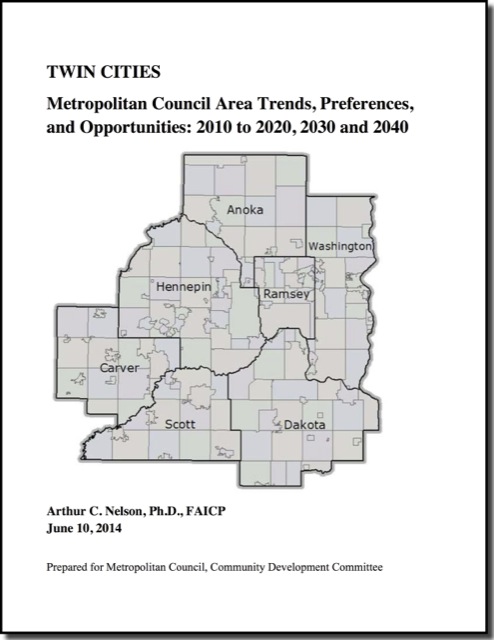

The Twin Cities Metropolitan Council is currently writing the Thrive Plan, which–like so many other urban plans today–aims to cram most new development into high-density transit centers. To justify this policy, the council naturally hired Arthur Nelson, the University of Utah urban planning professor who has predicted that the U.S. will soon have 22 million surplus single-family homes on large lots.

Click image to download a copy of the report.

“Demand for attached and multifamily housing in the Twin Cities will continue to grow,” trumpets the Met Council’s press release about Nelson’s report on Twin Cities housing. That, of course, is what the Met Council wanted Nelson to “prove,” which is why they hired him. However, his report can’t really justify the Met Council’s plans.

Nelson’s report predicts “a shifting mix of housing products demand for the next 30 years” such that the share of single-family homes on medium and large lots will decline from 37 percent to 26 percent; while homes on small lots will increase from 25 to 33 percent; and townhouses and multifamily will increase from 38 to 41 percent. Based on this, he says, “to meet housing demand by type in 2040 all new residential units will need to be attached options (apartment, townhouse, condominium) or small-lot detached homes.”

That sounds dramatic at first. But even if you believe his numbers, most of the change is from medium and large lot to small lot, not from single-family to multifamily, as the Met Council’s press release claims. Multifamily growing from 38 percent to 41 percent is not that big of an increase, and one that could easily be attributed to measurement error.

In fact, there are a lot of potential sources of measurement error in Nelson’s report. Most of the report is based on his interpretation of realtor surveys of people’s housing preferences in which lots of people said they wanted to live in “walkable neighborhoods.” Of course, if you ask people, “Would you like to live in a neighborhood where you can walk to shops?” a lot of people will say yes. But if you ask, “Would you prefer spending $400,000 on a 1,000-square-foot condo or $200,000 on a 2,000-square-foot home on a large lot?” few people would pick the condo.

Nelson thinks housing demand is changing because of “sweeping demographic changes” including an aging population, increasing numbers of ethnic minorities, and declining numbers of households with children. Yet, as shown by other studies, his assumption that these groups will necessarily prefer apartments, townhouses, or houses on small lots is not well grounded.

For one thing, he repeatedly uses the word “demand” but apparently does not know what this word means. Demand is not a point, like 619,000 Twin Cities households (the number he predicts will want to live in attached homes in 2040). Demand is a relationship between price and quantity, and prices never enter into Nelson’s analysis.

One reason why Nelson may not understand demand is that he seems to be arithmetically challenged in the first place. Page 26 of the report admits that “in the near term, 2020, demand for more homes on larger lots may still seem robust. The overall demand for such lots will increase by about 25,000 between 2010 and 2030—nearly 1,000 units annually.” Whatever you make of this “demand analysis,” 25,000 divided by 20 years is 1,250, not “nearly 1,000.”

A second problem is that the big change that Nelson predicts–a decline in the share of homes on medium and large lots from 37 percent to 26 percent–isn’t carefully measured by most of the surveys Nelson cites. Page 28 of the report notes that, in the surveys that do distinguish between lot size, a “small lot” is a quarter acre or less. Yet when many urban planners talk about small lots in walkable neighborhoods, they typically mean 25’x50′ lots, nearly nine of which would fit on a quarter acre. Do the people who answer vague questions about their housing preferences really understand this difference?

A third problem is that a lot of the data cited in the report has one source: Arthur C. Nelson. The report includes ten figures and thirteen tables, five of each of which say, “Source: Arthur C. Nelson.” The citations don’t even say, “Arthur C. Nelson, [year],” which would allow readers to pick out which of the ten papers in the reference section by Arthur C. Nelson the tables or figures are from. This makes the report even less persuasive than it already is.

Perhaps the most important self-citation in Nelson’s reference section is a 2006 article in the Journal of the American Planning Association where Nelson first predicted the future surplus of single-family homes. The article issued a clarion call to planners to lead the way to prevent this by forcing builders to focus on apartments instead. The Journal was honest enough to attach a critique by University of North Carolina planning professor Emil Malizia that pointed out that Nelson’s predictions were based on unreliable surveys whose results could have been “heavily influenced by the data collection method.”

In sum, Nelson predicts fairly small changes in housing preferences, especially between multifamily and single-family, and those predicted changes are based on specious data. Yet based on those predictions, the Metropolitan Council wants to make large changes in the Twin Cities’ housing mix, mainly a large increase in multifamily along its various rail lines. (Did I mention that the Met Council also wants to increase taxes so it can build more rail transit, which in 2012 carried all of 0.3 percent of Twin Cities commuters to work?)

The real question is: Just why should the Metropolitan Council, which was created solely to parcel out federal transportation dollars to cities and counties in the region, have anything to do with determining future housing supplies anyway? As Malizia pointed out in his critique of Nelson’s 2006 paper, if people’s preferences change, and housing is left to the market, the market will respond to those changes.

Not satisfied with that, the Metropolitan Council wants to dictate future housing choices by restricting low-density housing and subsidizing high-density housing near rail stations. These policies will make housing less affordable which (perhaps deliberately) will make the council’s prediction of an increasing desire for multifamily housing a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The Met Council has a few things working against it. It’s powers are limited. They only have some say in areas on main transportation corridors and where their sewer and water run. They can make things different but given the size of the sheer size of the region I’m not sure it’s meaningful.

While I haven’t had time to digest the Thrive plan, I do find the talk of attached housing to be curious. Is it an indirect acknowledgement that housing is becoming too expensive for a lot of people who are moving to the area? Or similar but that those who are the most well off, as a whole, are moving to what we today would call the exurbs? If the latter, the case of the Twin Cities, that would be 2 1/2 and 5 acre lots in townships like Credit River or Baytown where the Met Council doesn’t have water + sewer nor are their currently main arteries that enable them to have a say in local zoning.

The increase doesn’t seem notable compared to other numbers. It’s a small, single digit percentage compared to overall household creation. More so, all of these numbers seem to be for the 7 county metro area and not the 11 county metro. Throw in those other counties and the overall share of attached housing is smaller.

http://www.metrocouncil.org/Data-and-Maps/Data/Census,-Forecasts-Estimates/2012-Population-Estimates-by-Community.aspx

17,522 new households in 2012

http://www.metrocouncil.org/Data-and-Maps/Data/Census,-Forecasts-Estimates/Thrive-MSP-2040-Forecasts.aspx

households 2010: 1,021,456

household 2040: 1,509,190

Then there’s this trend that for some reason, despite the evidence, people as a whole don’t seem to understand has been occurring

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ruso.12024/abstract

More people moved into nonmetro counties from metro areas than in the other direction over the past two decades, according to analysis of annual county population estimates. Urbanization today is fueled by differential natural increase and higher immigration rates.

prk166,

Thanks for your thoughtful reply and useful links. You ask if the talk of attached housing is “an indirect acknowledgement that housing is becoming too expensive?” I doubt it, as housing in the Twin Cities remains pretty affordable.

The 2012 American Community Survey found median home values in the urban area were about 2.5 times median family incomes. For comparison, Indy and Houston were both about 2.2, making them more affordable, but MSP is still pretty affordable compared with, say, Denver at 3.2, Portland at 3.5, and coastal California areas that are between 5 and 7.

Given the Twin Cities’ affordable housing, it will be interesting to see how the Met Council tries to force most new housing in the TODs.