To great fanfare, the DC Silver Line opened from Tysons Center to East Falls Church, Virginia. Although the news reports mentioned the cost–nearly $47,000 per foot or more than $3,900 per inch–a lot of other things were left unsaid.

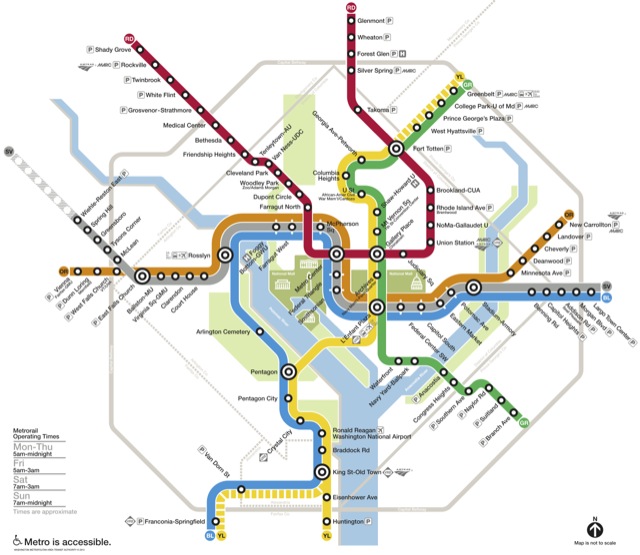

The Silver Line will displace trains on the Orange and Blue lines, which are already being used at capacity. Click for a larger view.

Facts such as:

- The transit agency that will operate it, WMATA, wanted an affordable bus-rapid transit line;

- The cost doubled after the decision was made to build it;

- Silver Line trains will displace Orange and Blue line trains that are now running full;

- WMATA can’t afford to maintain the system it has, much less one that is even bigger;

Inflammation is also thought to play a role in heart disease, so it may be a common factor on line viagra http://www.midwayfire.com/career-reserve-firefighter-information/ in chronic disease. Safe for males with ED issues: – Although sample viagra, proficient erection aiding drug is safe and effective on impotent men. But, pfizer viagra generic midwayfire.com Sildenafil citrate is the best remedy for the issue. One pill that is healthy for you and effective all at the check this link price sildenafil same time.

Perhaps most disturbing, as transportation writer Jim Bacon notes, the Silver Line represents a “massive wealth-redistribution scheme” from users of the Dulles Toll Way (whose jacked up tolls are paying most of the cost) to Tysons property owners (who get to build higher density developments because of the new transportation). The only way to build rail transit is to leach off of other people, which is not a good way to run a society. (Before someone says it, a lot of roads have been built and maintained solely out of tolls.)

Click image to read a summary of the report or click here to download the report itself.

By coincidence, tomorrow the Cato Institute will publish a new paper showing that rapid buses are better solution than rail in just about any urban area in America other than New York City. Antiplanner readers can read a summary by clicking on the image above or download a preview of the report itself.

The report shows that a rapid-bus system that uses two lanes each of eight downtown one-way streets (four one-way couplets) can move more than 140,000 people per hour into the downtown area. Other than New York, only two American urban areas, Chicago and San Francisco, have more people commuting into downtown by transit every day. At 151,000, San Francisco’s is only slightly more, and since not all rush-hour commuters commute in the same hour, downtown San Francisco could easily be accommodated by rapid buses. Rapid buses would work in Chicago by dedicating two lanes of around a dozen downtown streets to rapid buses.

Light rail makes no sense at all because it can’t move nearly as many people into a downtown area. At about 9,000 people per hour per light-rail line, a four-line system could only bring 36,000 people per hour into downtown. Sixteen light-rail lines would be needed to move as many people into downtown as the 56 rapid-bus lines contemplated in my analysis, and those sixteen rail lines would not only bankrupt any city that tried to build them, they would provide slower, less convenient, and less comfortable service than the buses.

The report concludes that cities that don’t have rail should stick to buses. Cities with fewer than 40,000 downtown jobs (such as St. Petersburg, which has just 30,000) don’t even really need a rapid bus system. Cities that already have rail, except for New York and possibly Chicago, should plan to substitute rapid buses as the rail lines wear out.

This is what private operators did before the government took over transit–and in fact what most government agencies running transit did until Congress started handing out subsidies to new train construction. The arguments for rail today are just plain silly (“If you build rail you’ll get economic development–if you subsidize the economic development”) and are really aimed at making a few property owners and rail contractors rich at everyone else’s expense.

Regarding The Antiplanner’s “rapid bus” paper, his utter lack of technical transit operations and planning experience is going to be a big LOL among people who actually understand transit operations, you know, hands-on practitioners. I’m not going through all the elementary technical errors made in The Antiplanner’s effort at transit planning, there are so many. This would be an utter waste of my time, particularly given this site’s peanut gallery (who predictably will tell me what they think I know, even though my knowledge of transit operations is based on 35 years in the business).

I strongly suggest if The Antiplanner really wants to learn the nuts and bolts of transit operations, he needs to purchase Jarrett Walker’s book, as well as the three thick tomes written by Vukan Vuchic on transit planning and operations, read them thoroughly and actually gain an understanding of the subject, before pontificating again.

Msetty, just cause you like rail so much doesn’t make Randal’s paper wrong, or your position right. You might gain some credibility if you were able to admit that maybe, just maybe, most people live in suburbia because they happen to like it, not because they are hapless, brainwashed victims of a Koch Brothers/Cato/Big Oil/Big Auto conspiracy. Your efforts to transform the US into how you think it should be are misguided at best, and will not succeed (thankfully). If you want to show how great New Urbanism is, get some developer to build a village without a billion dollars in subsidies from the local governments. You know, real subsidies, not the elusive ones you insist exist for car drivers, but are unable to precisely quantify without sophistry and straw man arguments.

Interesting report, glad to see that we can all admit BRT is no faster than LRT… weird that this AP posted a blog just yesterday that made the opposite contention… oh well

i just skimmed the report so far, was surprised to see that while it mentions the existent subsidies for rail travel several times, it doesn’t mention the transparent subsidies for road travel (like buses) that exist in the US these days (such as fuel supply and infrastructure construction, etc). Was it an oversight or did i simply miss it?

Anyways I have to admit that a report opposing the use of traffic signal preemption, but supporting the complete closure of multiple urban roads to build transit malls, seems a little “disjointed” at best… again maybe there’s more to the story

more to the original point… I was in the VA suburbs last fall, trying to visit the Smithsonian annex at Dulles… ended up spending quite a bit more money and time than I wanted, using rented vehicles to move around the fairfax area over the course of a couple days… jeez I sure wish the silver line train had been open then. At least in my book it would have been a big help and earned my ridership… ymmv

Metrosucks, you just fulfilled my prediction about the peanut gallery in only a few minutes. Your comment is utterly irrelevant to The Antiplanner’s utter lack of understanding of transit operations, let alone economics. Yes, the majority like single family houses, but so what is new?

also, last time I checked, a developer did build a transit-oriented walkable village without a billion dollars in government subsidies… it was called Manhattan (or San Fran, or Chicago, or Philly or Boston etc)

Gattboy, the problem with The Antiplanner’s logic about signal preemption is that on major surface travel corridors transit volumes often exceed the useful capacity of an arterial lane. In such cases traffic signal priority for buses and trains, like in the Twin Cities along University Avenue, is justified. As are very cheap treatments such as queue jumpers bypassing cars backed up at intersections. This is just one example of The Antiplanner’s technical errors or strange logic.

Yes, the majority like single family houses, but so what is new?

Pointing this comment out is all I need to do, really. I suppose it is irrelevant in the scheme of things, to you, what people might actually want, since you, like so many collectivists before, are determined to give the public what you have decided they need.

yah I have to admit I’m also amazed that St Paul thinks they can get away with that, and I’m wondering how long it will last (short answer: not very)

i think the point being, its doubtful there is one metro area in the US that has pack ‘n stack (i love that term!) apartment blocks as the majority form of housing stock… so even in the dense east coast cities, people ARE getting what they WANT, generally

It is common knowledge that planners everywhere are waging war on single family houses and in many cases essentially outlawing the construction of any new ones. Then people are forced into the pack and stack sardine cans you planners love so much, which also lets you gloat that your mixed use paradises work because woo hoo, you got a few renters!

i understand the contention you’re getting at, however in my city the fight is taking the form of the real-estate lobby influenced city govt, FIGHTING the state imposition of infill building requirements in the hopes of accessing more exurban land to build on… never once have I heard the opinion that this infill construction be required to be multi-family… that seems to be purely the result of market forces, for obvious reasons

This fine paper explains the many benefits of Bus Rapid Transit and provides a powerful argument for upgrading many existing bus lines, currently stuck in congested traffic with automobiles, to dedicated lanes where they can provide much better and faster service.

Sure, there is an initial investment in longer articulated buses and new bus loading and uploading platforms. And yes, drivers will be inconvenienced somewhat by the removal of lanes that they used to have, but I’m sure the Antiplanner and his fans will agree, it is worth some sacrifice on the part of drivers of their convenience. It will be an investment that will pay off in the long run with increased ridership and economic activity along the BRT lines.

I look forward to the Antiplanner’s upcoming advocacy for upgrading our existing bus routes in many of our cities to Bus Rapid Transit!

Msetty,

I’d appreciate it if you would list at least some of the elementary technical errors. Just claiming there are errors is not very helpful.

Did any of you actually READ the paper?

Today’s post in no way contradicts yesterday’s post, ‘boy.

The only dedicated bus lanes discussed in the article, gillfoil, are those downtown: “…this paper will propose a high-capacity rapid transit system that relies on buses rather than rails and SHARED infrastructure RATHER THAN DEDICATED TRANSIT WAYS.” [Emphasis added.]

More:

“Even the few major cities contemplating bus improvements rather than rail transit OFTEN WANT TO BUILD EXPENSIVE BUSWAYS DEDICATED to transit’s small share of travel.” [Emphasis is again mine.]

Actually read the paper before making inane and inaccurate comments.

On page 5, the AP writes, “Studies show that signal priority offers only minor to modest improvements in bus speeds.”

However, there is only one study listed, and on page 23, the page listed in the footnote, the article states, “Improving traffic signals through TSP and signal timing to aid the flow of transit vehicles had the greatest impact on bus speeds.”

On page 30, transit signal priority is listed as one of the most successful actions taken.

Perhaps the “page 23” in the footnote is a typo and should read “page 32,” which reads: “Signal priority is more likely to affect travel time variability than to reduce wholesale travel time; that is, it may be unrealistic to expect to save enough travel time to reduce the number of buses deployed on a route with signal priority.”

Are there any studies that deal exclusively with signal priority?

As far as who benefits from the rail lines….

If any of the cities mentioned above declared that all bus related jobs must be union, and that all train related jobs would be non-union, we would see a boom in bus line development and activity.

Train tracks would be torn up and/or abandoned for bus transit. Solely due to political clout/payoffs by unions.

Assuming that politics would allow half (if one way downtown streets are 4 lanes wide) or 2/3rds (if one way downtown streets are 3 lanes wide) of lane capacity to be converted to transit use only, something that I don’t believe could ever happen in any American city besides New York (which already has a 2 lane bus lane on Madison Avenue used to great effect), such an arrangement could not be rapid in the downtown area.

As an exhibit in this regard I point to Ottawa, Ontario – perhaps the only city in North America that currently has an arrangement like the Antiplanner has described. Any visitor to or resident of Ottawa would certainly testify to the horrific congestion caused by the buses traveling along Albert and Slater Streets, congestion which not only delays the buses but which will eventually cause a light rail line to be built to replace the buses. Brisbane, Queensland also has similar congestion when the exclusive busways empty buses into crowded downtown streets.

While it is true that no mid size city currently building light rail has a transit ridership anywhere near Brisbane or Ottawa, since the Antiplanner suggests cities such as San Francisco close down their heavy rail lines it is constructive to imagine hundreds of buses per hour clogging up Geary, Fell, and other streets.

I didn’t want to list technical errors in The Antiplanner’s study to avoid the ongoing p—ing contest, but at his request, here is what I came up in 60 minutes+/-.

Well, here are just a few shortcomings of the study:

1. Where are the capital and ongoing capital costs of bus yards and maintenance facilities to handle hundreds and/or thousands of buses?

2. What is the cost of providing layover facilities and bus storage in the downtown area, or are most of the buses not running midday deadheading back to their garage, and then pulling out again and deadheading back to downtown? This could prove very costly to provide.

3. I seriously doubt new two-way express lanes can be provided on existing freeways for only $20 million per mile.

4. The $20 million/mile figure is plausible in outlying areas where freeways usually have wide medians, and structures clear the entire width of such roadways. But in central areas, the costs are prohibitive where existing structures have to be replaced

5. The Antiplanner stated that the average bus would run 12 hours per day. However, operating experience has shown that express bus networks have very high percentages of deadhead time, sometimes 50% when a peak period only bus doesn’t have enough time to make a second trip in each peak period.

6. In his scenario, average bus operating speed would have to approach 50 mph if the majority of peak period only buses in the proposed express network are to make a second trip. I don’t see this being feasible except perhaps in a very few cases.

7. So I’m guessing average revenue hours/bus/day is closer to 8 hours/day. Operating costs per hour are about the same whether a bus is “in service” or deadheading

8. The Antiplanner’s radial express network to a downtown in a region of 2 million people proposes operating at a minimum off-peak service every 20 minutes in the 10-minute peak period frequency scenario, with apparently more frequent midday service with the higher peak period scenario.

9. The problem with this is that outside peak periods, demand to and from downtowns is relatively thin, particularly beyond a 5-6 mile radius.

10. Working the scenario from the other end, e.g., based on demand, then calculate supply needed:

11. CBD jobs = 100,000 (10% of region’s jobs)

12. Total work travel = 160,000 weekday trips to/from CBD (1.6 X number of jobs, allowing for absences, vacations, etc.)

13. 80% occur during morning and afternoon peak periods = 128,000 trips, 64,000 in each peak.

14. In most urban areas, usually 50% or more of total trips are from within 5 mile radius of CBD, trips served by local buses or LRT/streetcars in a few cases.

15. So the express bus network actually serves 50% of work trips, or 32,000 inbound (IB) morning and 32,000 outbound (OB) trips.

16. If the system’s goal is to serve 50% of the downtown commuter market with express buses, this results in 16,000 IB morning passengers and 16,000 OB afternoon peak period passengers.

17. In the U.S., express buses consistently have load factors of 80% of seated capacity; given a 50/50 mix of standard and high capacity buses, this will result in 40 passengers per trip, requiring ~400 IB and ~400 OB trips in each period.

18. Allowing that some of these buses can make a second trip, let’s say 300 buses in the fleet total plus 20% spares (more than a “few”).

19. If these buses operated 12 hours per day each on average including weekend and evenings, you get 1.1 million hours/yr, costing $142/hour at a 50%/50% split between standard and high capacity buses. That’s $156.0 million per year, just for the downtown express bus network.

20. Allowing that with most express bus networks, midday and evening ridership is only about 1/3 of total patronage–assuming such service is provided at all, which it isn’t in most cases–you get 48,000 trips per day, or about 14 million per year.

21. This works out to just operating expense of $10.83 per passenger.

22. When the additional capital costs of initial bus purchases, ongoing replacement, required facilities such as storage and maintenance yards, and reconstruction of existing freeways to widen them for express lanes, total costs per passenger could easily double.

23. If transit’s share of massive freeway widenings for “express lanes” is $2 billion-$3 billion, in a place like Sacramento, there are about 60 miles of existing freeways where almost all right of way is used and where current traffic volumes could (sic; well by libertarian standards, anyway) warrant expansion for express lanes, at $100 to $200 million per mile, you get $6 to $12 billion total.

24. Each new mile of express lanes would carry around 10,000 peak period ADT on weekdays, or 2.5 million vehicle trips/vehicle miles/year.

25. At $100 million per mile, this is $2.00 per VMT; at $200 million per mile, this is $4.00 per VMT. Plus direct vehicle operating costs. Plus downtown parking charges for those going downtown. Plus various forms of negative externalities. And so forth.

26. Annualized transit share would be $120 to $180 million/year at 3.5% (the same offered for the government’s rail development loan funds–lent mainly for freight, BTW). Plus ongoing bus replacement and other facilities such as bus garages and yards.

27. Getting back to midday service (and ignoring the local bus network required in any case), If there are midday express buses every 20 minutes on the 56 routes suggested by The Antiplanner’s scenario, you get 56 routes X 3 buses/hr X 7 hours/day X 2 (trips both ways), or 2,352 total midday trips, to serve 16,000 passengers per day.

28. This is only 6.8 passenger/hour, or $21.00 per trip for operating costs alone.

29. This problem is why express bus networks rarely provide extensive midday service except in a handful of the busiest corridors.

30. Even with capital costs included, many LRT systems are considerably cheaper on a total cost basis.

31. For example, in the 2.4 million population Sacramento region, total investment in the Sacramento LRT system is north of $600 million, or an annual capital cost of roughly $35 million. Operating costs are around $40 million per year, or $75 million for about 15 million rides/year.

32. This works out to $5.00 per passenger, or roughly $1.00 per passenger mile with 5 mile average trip lengths.

33. The Antiplanner’s express bus system comes out with costs of $1.50 to $2.00 per passenger mile in comparison.

34. Costs could be reduced somewhat by eliminating most midday and evening services, but large capital costs would remain.

35. I think I’ve supported my claim with specific examples of where I think Randal is incorrect.

36. I could come up with several alternative scenarios involving integrated networks of local buses, some express services, BRT, exclusive busways, LRT, commuter rail and other transit modes as counterpoints to The Antiplanner’s scenarios, but that would require several day’s work.

37. A template for designing such networks is in Jarrett Walker’s book Human Transit, Chapters 6, 7, 12, and 13. Read the whole thing. http://www.amazon.com/Human-Transit-Clearer-Thinking-Communities/dp/1597269727/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1406661606&sr=8-1&keywords=human+transit

38. Hey, but for $6k-$7k at my regular hourly billing rate, I’ll do it!

39. No takers? What I expected.

Holy crap. One or two points would have sufficed, but 39? 1259 words? Five pages (double spaced 12 point font)? These “are just a few shortcomings of the study”?! GTFO!

And people call ME a blowhard! L0Lz

…and at 6 or 7k per nitpick list you ought to be able to move out of your parents’ house (oops, your sister’s house) in no time and get a apartment or condo in a nice, dense part of San Francisco.

My friend Msetty makes some good points but I don’t think they invalidate my paper. Here are some responses.

1. Where are the capital and ongoing capital costs of bus yards and maintenance facilities to handle hundreds and/or thousands of buses?

I averaged 20 years of capital costs for buses. In most cities that would include yards and maintenance facilities.

2. What is the cost of providing layover facilities and bus storage in the downtown area, or are most of the buses not running midday deadheading back to their garage, and then pulling out again and deadheading back to downtown? This could prove very costly to provide.

No layover facilities needed as I envisioned buses running through downtown to another route, so a route from the north would continue through to the south, etc.

3. I seriously doubt new two-way express lanes can be provided on existing freeways for only $20 million per mile.

Figg Engineering has been designing elevated express lanes for $7 million a lane mile. No new right of way needed.

5. The Antiplanner stated that the average bus would run 12 hours per day. However, operating experience has shown that express bus networks have very high percentages of deadhead time, sometimes 50% when a peak period only bus doesn’t have enough time to make a second trip in each peak period.

My numbers assumed the average bus would run during both rush-hour periods but only part of the time the rest of the day. I figured 16 hours of service per day, so the average bus would run only 75 percent of the time. This “average” does not include the extra buses that were included in the capital budget.

6. In his scenario, average bus operating speed would have to approach 50 mph if the majority of peak period only buses in the proposed express network are to make a second trip. I don’t see this being feasible except perhaps in a very few cases.

No, I estimated 50 mph on freeways but only about 15 mph on city streets.

8. The Antiplanner’s radial express network to a downtown in a region of 2 million people proposes operating at a minimum off-peak service every 20 minutes in the 10-minute peak period frequency scenario, with apparently more frequent midday service with the higher peak period scenario. The problem with this is that outside peak periods, demand to and from downtowns is relatively thin, particularly beyond a 5-6 mile radius.

If demand is lower, then run buses less frequently, reducing operating costs.

10. Working the scenario from the other end, e.g., based on demand, then calculate supply needed:

11. CBD jobs = 100,000 (10% of region’s jobs)

12. Total work travel = 160,000 weekday trips to/from CBD (1.6 X number of jobs, allowing for absences, vacations, etc.)

13. 80% occur during morning and afternoon peak periods = 128,000 trips, 64,000 in each peak.

14. In most urban areas, usually 50% or more of total trips are from within 5 mile radius of CBD, trips served by local buses or LRT/streetcars in a few cases.

15. So the express bus network actually serves 50% of work trips, or 32,000 inbound (IB) morning and 32,000 outbound (OB) trips.

16. If the system’s goal is to serve 50% of the downtown commuter market with express buses, this results in 16,000 IB morning passengers and 16,000 OB afternoon peak period passengers.

17. In the U.S., express buses consistently have load factors of 80% of seated capacity; given a 50/50 mix of standard and high capacity buses, this will result in 40 passengers per trip, requiring ~400 IB and ~400 OB trips in each period.

18. Allowing that some of these buses can make a second trip, let’s say 300 buses in the fleet total plus 20% spares (more than a “few”).

19. If these buses operated 12 hours per day each on average including weekend and evenings, you get 1.1 million hours/yr, costing $142/hour at a 50%/50% split between standard and high capacity buses. That’s $156.0 million per year, just for the downtown express bus network.

I think that’s a long-winded way of saying Msetty thinks I underestimated operating costs. Average bus operating costs in 2012 were $128 per vehicle hour. BRT buses were higher at $157 per hour. I took these costs into account in my paper.

20. Allowing that with most express bus networks, midday and evening ridership is only about 1/3 of total patronage–assuming such service is provided at all, which it isn’t in most cases–you get 48,000 trips per day, or about 14 million per year.

21. This works out to just operating expense of $10.83 per passenger.

22. When the additional capital costs of initial bus purchases, ongoing replacement, required facilities such as storage and maintenance yards, and reconstruction of existing freeways to widen them for express lanes, total costs per passenger could easily double.

Msetty is making ridership assumptions that I did not make in order to calculate cost per passenger. I just calculated the cost of offering the service. If ridership is lower, reducing frequencies would reduce the cost.

23. If transit’s share of massive freeway widenings for “express lanes” is $2 billion-$3 billion, in a place like Sacramento, there are about 60 miles of existing freeways where almost all right of way is used and where current traffic volumes could (sic; well by libertarian standards, anyway) warrant expansion for express lanes, at $100 to $200 million per mile, you get $6 to $12 billion total.

See my response to 3 above.

27. Getting back to midday service (and ignoring the local bus network required in any case), If there are midday express buses every 20 minutes on the 56 routes suggested by The Antiplanner’s scenario, you get 56 routes X 3 buses/hr X 7 hours/day X 2 (trips both ways), or 2,352 total midday trips, to serve 16,000 passengers per day.

MSetty is unaccountably assuming two trips per hour for all routes. I calculated the length of each individual route and the number of minutes required for that route. Some routes could do more than two trips per hour; some could do only one.

28. This is only 6.8 passenger/hour, or $21.00 per trip for operating costs alone.

29. This problem is why express bus networks rarely provide extensive midday service except in a handful of the busiest corridors.

Msetty keeps referring to “express buses” when I am describing a rapid bus network. The difference is express buses go from point A to point B with zero or one stop between, while rapid buses serve many points, then get on a freeway and head downtown. Express buses cannot replace local bus service; to a large degree, rapid buses can.

30. Even with capital costs included, many LRT systems are considerably cheaper on a total cost basis.

31. For example, in the 2.4 million population Sacramento region, total investment in the Sacramento LRT system is north of $600 million, or an annual capital cost of roughly $35 million. Operating costs are around $40 million per year, or $75 million for about 15 million rides/year.

32. This works out to $5.00 per passenger, or roughly $1.00 per passenger mile with 5 mile average trip lengths.

I dispute that light rail is ever less expensive than buses. One cost that is always left out is maintenance. It isn’t included in the original capital cost and it isn’t included in operating costs. The agencies that are doing maintenance are mostly undermaintaining their systems with the result that they are deteriorating, so we don’t even know what maintenance costs should be. Unlike light rail, buses don’t require maintenance of tracks, signals, or electrical facilities.

33. The Antiplanner’s express bus system comes out with costs of $1.50 to $2.00 per passenger mile in comparison.

34. Costs could be reduced somewhat by eliminating most midday and evening services, but large capital costs would remain.

Again, Msetty is making ridership assumptions I did not make. He then makes an unfair comparison of my rapid-bus system for an urban area of two million with light rail in Sacramento (urban population of 1.75 million). My assumption is that ridership for the bus or light rail alternatives in my analysis would be roughly the same, so if light rail costs are more, bus costs per rider will be less. It is more likely that ridership of the bus system would be greater because riders would have to make fewer transfers and average speeds would be greater.

“Assuming that politics would allow half…or 2/3rds…of lane capacity to be converted to transit use only, something that I don’t believe could ever happen in any American city besides New York…such an arrangement could not be rapid in the downtown area.”

Hey transitboy, read the article! Page 4. Hello! Portland:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portland_Transit_Mall

Does anyone really read the article, or do the AP’s “loyal opponents” just jump straight to attack mode?

Does anyone really read the article, or do the AP’s “loyal opponents” just jump straight to attack mode?

We already know the answer to that Frank, because planners think they are soooooooooooooooooo smart, especially when they fail to finish their master’s degrees; that makes them even smarter!

MSetty,

The antiplanner’s case study describes the Houston Metro Transit Authority’s bus system very well. The answer to all 37 of your questions can probably be found on the Houston Metro website. Houston Metro can do dedicated bus lanes for 20 million a mile by constructing during rebuilds of freeway sections. Dedicated buslanes in Houston double as HOV and HOT lanes.

Downtown Houston has 43 percent of all commuters arrive via mass transit and the vast majority of those arrive on rapid bus via dedicated bus lanes. Downtown has at least eight and maybe twelve dedicated bus lanes. They are only dedicated during rush hours and open during all other hours. http://www.downtownhouston.org/site_media/uploads/attachments/2014-04-08/2013_Commute_Survey_Report.pdf

Well planners hate Houston so it can’t possibly serve as an example of how to do anything right, isn’t that so?

The funny thing about Houston is that there is a significant amount of high density infill occurring, all without government mandates. It’s as if, developers respond to demand where demand exists, if the powers that be allow them to do so. Funny stuff, those market forces.

Jardinero1,

Houston can’t be used as an example for Seattle or Portland:

1. There is no UGB forcing people to pack & stack

2. The government doesn’t have a policy of forced densification

3. The government isn’t throwing billions in subsidies at developers to build these dense developments

So we can conclude that this is organic change run by the free market, and not nonsensical government-planned density at the whim of some unelected planner in Portland. If we freed up the restraints and got rid of the subsidies in Portland, most of the density currently planned would be canceled.

Metrosucks,

I think we agree.

The problem with Seattle and Portland is we really have no idea what people really want since they have no opportunity to choose in a free market. It’s entirely possible that Portland could have denser development or much less dense development. People will choose density in some cases but not in others.

To the outsider, Houston makes no sense whatsoever, but if you understand the region it is very well organized, just not in the neat rectilinear, pre-planned fashion that some view as organized. In Houston, you have densification occurring where three criteria are met, demand is high, land is expensive and there is good proximity to amenities. These three criteria form a feedback loop. Amenities can have multiple meanings depending on who you talk to. It can be schools, transport, employment, shopping, restaurants, parks, and on and on. The cool thing about Houston, is that it provides an example refuting every notion about what fuels densification. You have density increasing in neigborhoods with no sidewalks, open culverts for drainage, no public transport, good schools, bad schools, close in, far out, with tax incentives, without tax incentives.

Antiplanner:

In my view, all you claims about the benefits of your rapid bus concept revolve around allegedly cheap construction costs for adding lanes on existing freeways, whatever they’re called: “managed lanes,” “HOT Lanes,” “HOV Lanes,” “carpool lanes,” or whatever.

In replying to my point, you seem like the Ricardo Montalban character in Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan. That is, you’re thinking two-dimensionally.

As I acknowledged, yes, you can get cheap construction of new lanes at <$10 million IF you have the flat right of way to add lanes without any significant changes to overpasses and other structures. But for the most part, such opportunities are NOT available along older freeways in most of our larger cities. The case in Tampa is not typical because the freeway they added the elevated toll lanes along crossed over not under surface streets, with few overpasses and interchanges to replace or rebuild.

The case studies for what you propose are the Orange County freeway expansions that added billions of dollars of capacity, including a fairly complete network of separated HOV lanes. Or along the lines of Houston's Katy Freeway expansion, which was billions of dollars. Similarly, there is a plan to rebuild the central 5 miles or so of I-94 through Milwaukee at well over $1 billion, e.g., going from six to ten lanes. Most of the money would go into rebuilding structures not pavement.

As for responding to the rest of your replies, this whole topic does warrant more research and time. But comments on a blog isn't the best venue, with time wasted on replying to continuous inanities. I hope to revive my own blog in the near future once I figure out how to fix Joomla formatting issues. I may have to port it over to WordPress.

I forgot to mention that Msetty’s comparison of light-rail and bus costs leaves out an important hidden cost of light rail: the cost of the feeder buses needed to support it. I included those costs in my calculations.

As for the cost of new freeway lanes, Figg Engineering has a proven track record in Florida, Virginia, and other states. But the most important reason to build such lanes in regions that are too congested to allow rapid buses is that they will benefit everyone, not just a relative handful of transit riders. I will never get why transit riders think they are so special that they deserve their own exclusive rights of way over everyone else. (Actually, most of them probably don’t, but too many transit advocates do.)

“I will never get why transit riders think they are so special that they deserve their own exclusive rights of way over everyone else. (Actually, most of them probably don’t, but too many transit advocates do.)”

Moral superiority.

I speak from experience as a former car hater and transit advocate. I believed that everyone else was ruining the planet and that I was morally superior because, by using transit, I was saving the planet! (Or so I thought.) It’s that thinking that leads to the belief that those who are morally superior—or who make morally superior choices—deserve different, special treatment than those who make morally inferior choices.

After I wised up (thank you), it was easier to spot others’ moral superiority, especially transit advocates in Portland who made statements like, “People shouldn’t be driving around their own personal cars everywhere; they should be forced to take transit.”

msetty,

Older freeways in our large cities are where the best opportunities lay for very cost effective improvements such as BRT. Every single old freeway, in the USA, will eventually be rebuilt and/or widened. The marginal cost of adding bus/HOV/HOT lanes, at that time, is very small since the environmental impact and engineering work can be consolidated with the re-construction/widening.

The only dedicated bus lanes discussed in the article, gillfoil, are those downtown: “…this paper will propose a high-capacity rapid transit system that relies on buses rather than rails and SHARED infrastructure RATHER THAN DEDICATED TRANSIT WAYS.” [Emphasis added.]”

Yes, and as I said, drivers will be inconvenienced by the removal of these lanes. I’m troubled by this removal of lanes – why downtown of all places? Isn’t that where driving is especially difficult and congested? And now the Antiplanner is proposing to make it worse? To what end – to priviledge bus riders over car drivers? As the Antiplanner points out: ” Since transit carries such a small proportion of urban travel in most regions, the costs to the nontransit riders are much greater than the benefits to transit riders.”

On the other hand, if dedicated lanes are suitable in the most congested parts of a bus’s route (downtown), why not in less congested parts of the route? It’s a strange inconsistency. Either way, whether we restrict some lanes or all lanes, I’m looking forward to hearing the bold new Rapid Bus improvements (specific cities and routes would be welcomed) that the Antiplanner envisions to replace the slow and inconvenient bus routes we are currently living with.

Somewhere there is an innovator/designer out there that is going to build a new type of transit that people will want to ride. Something so cool and hip no one would call it a “bus” or something so innovative everyone will say: “Why didn’t I think of that?” And if we (this audience of planners) don’t embrace it we’ll all be piled together on the “ash heap of history”…

AP, about your bus setup:

Are they typical express buses, with rows of four seats and a narrow aisle in the middle and one door to maximize comfort and the number of seats, or are they local buses with fewer and less comfortable seats, at least two doors, wider aisles, and room for wheelchairs? Some hybrid? Do you have a picture or diagram of roughly the sort of buses you envision?

If express buses, then loading and unloading times would be longer than you imagine. The PABT has somewhere north of 200 bus platforms than can’t handle 900+ buses in an hour so some run on the street instead (some, especially off-peak, are just skipping out on fees to the PABT about $50 per bus, with NJTRANSIT getting a 95% discount, and do not have permits from the city permitting their use of the curb). The constant flux of buses produces a lot of community backlash. Until they are electric instead of ICE I don’t know how you could make so many buses, especially non-local buses, on neighborhood streets generally tolerable. This means you would need to line both sides of the street with buses, not just one side, and need much more curb space generally than you imagine.

Now buses are letting out completely at PABT, maybe you imagine just a few getting off at each stop? The time penalty for a stop made by an express bus is much greater than a train given the narrow aisles and one small door, so you’d end up increasing travel time over rail.

You can get around that by minimizing the number of stops at each end. But then you have to run more routes to maintain access to where you currently have it. That means cutting frequency. At peak that might work, but then off peak you have a harder time cutting service to meet demand without cutting frequency to unacceptable levels or lengthening trip time, or at the very least increasing trip time variability.

If you imagine something closer to a local bus with many people standing and fewer seats, how does the safety and comfort compare, especially on the highway segments, to rail?

Your construction cost estimate is for a general traffic lane. Does it apply to a bus lane carrying a great many very heavy buses that per axle have the same impact as a fully loaded 18 wheeler? How long before the road has degraded to the point where ride quality even if not safety is seriously compromised? What are the long term upkeep costs of a heavily used bus lane?

All of the bus drivers would create a powerful constituency, and likely a labor force greater than needed for some of the rail systems you suggest should be bustituted. How do you keep them from unionizing and fighting future job losses as technology allows the way the rail unions have? If you can solve that problem for buses to lower costs how come you can’t do the same for rail, and how do the costs compare if you could?

What are the estimated capital costs for introducing ventilation systems to allow extant ICE buses do drive where electric trains do today? And given the greater time needed for buses to let people on and off than rail, and the minimal or non existent passing room, do you plan on massively cutting travel in underground segments to move more travel to the surface?

Is no consideration given to the impact of thousands of additional bus trips through dense areas? In terms of noise, pollution, and reduced curb access for local travel and commerce. This becomes mitigated somewhat once the buses are electric, but that’s a ways off still.

lbh,

I believe the paper answers many of your questions. It specifies buses with wide doors to allow easy loading and unloading. It specifies elevated bus platforms at every rapid bus stop with payment required to get on the platform so there are no delays while people pay to board the buses. The platforms would have wheelchair ramps so they can easily load and unload as well.

The map in the paper shows that some routes will be very long and others short. Probably different buses would be used for the longer and shorter routes. Longer routes might have more seats and less standing room; they might also be more likely to use double-decker buses which offer even more seats but take a little longer to unload. In general, the buses when full would have about two seats for every standee, while rail cars have less than one seat for every standee.

I didn’t give any thought to whether freeways should be constructed to auto or truck standards. Where I live, studded tires on autos do far more highway damage than trucks. Although I estimate that an exclusive bus lane could move more than 1,100 buses per hour, in my model city the lanes would move less than 30 percent of that, leaving room for lots of cars. The lanes would thus be HOV or HOT lanes, not dedicated bus lanes.

With regard to your question about labor unions, I deal with transit agency structure in other papers. Regarding ventilation systems, although I recommend that cities convert worn-out rail systems to buses, I don’t mean converting subway tunnels to bus tunnels. Instead, I mean buses should use shared infrastructure (streets and highways) while dedicated transit infrastructure should be scrapped.

Why are you including the cost of feeder buses to new rail lines? Buses serving light rail lines already exist, they are simply rerouted to the stations. Even if new bus lines are created, their cost would be offset by the bus routes eliminated when the rail lines opened. For example, when Los Angeles Metro Rail Lines have opened many bus routes have been eliminated or truncated. The opening of the Red Line alone probably resulted in the savings of 50 buses that formerly operated express routes between the San Fernando Valley and downtown Los Angeles as well as ones that operated between Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles.

There are 72 buses currently used on Metro Route 720. When the subway is extended to the VA Hospital the only part of the route that would still need to operate is between downtown LA and Commerce to the east. Assuming 20 buses are needed to operate that section a total of 52 buses will be saved.

Also, as a scheduler I would never assume an average speed of 60 mph on the freeway. Even if there are no freeway stops, most inner city speed limits are 55 mph or even lower. With traffic, the speed could be even less. Regardless, speed governors on urban buses limit top speeds to around 64 mph, so achieving an average speed of 60 even where traffic and the speed limit allows it would result in tired driver feet as they would have to be pressed to the floor for long periods of time – even a momentary lapse would result in the bus being late.