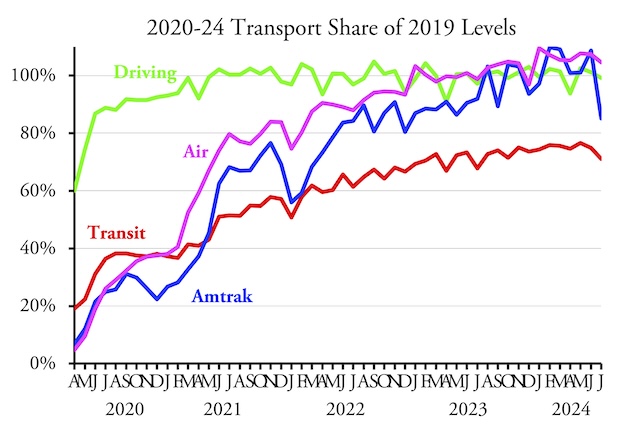

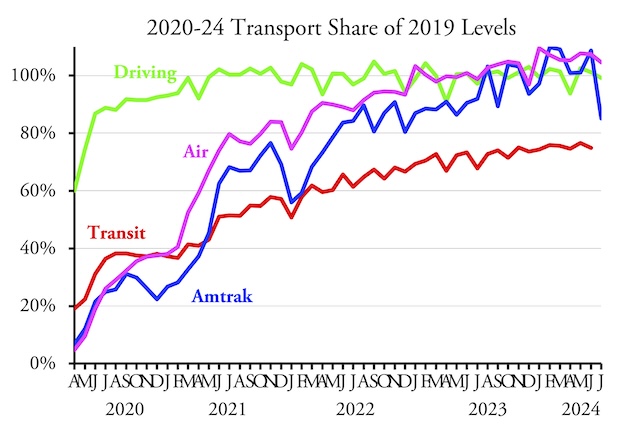

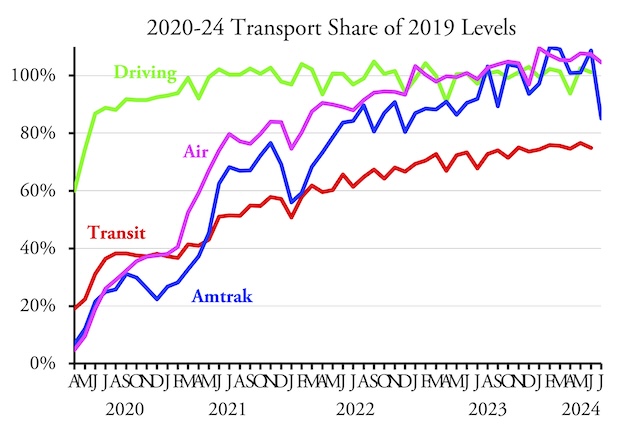

I’m back from Japan and mostly recovered from jet lag. I may write about my Japan experiences next week but first it’s time to look closely at the July transit data posted by the Federal Transit Administration the day I left the states.

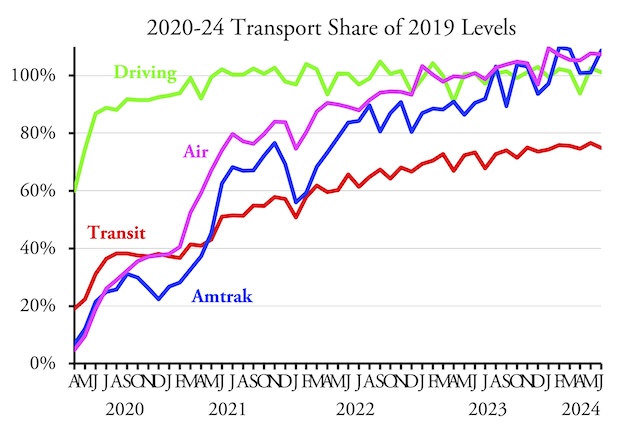

Based on a quickie analysis on my iPhone I previously reported that transit carried only about 64 percent as many riders in July of 2024 as the same month of 2019. However, I warned that I wasn’t certain about this as I was having trouble analyzing a 15 megabyte spreadsheet on the phone. In fact, the number is 71.1 percent, which is better than 64 percent but worse than any month since July 2023. Continue reading