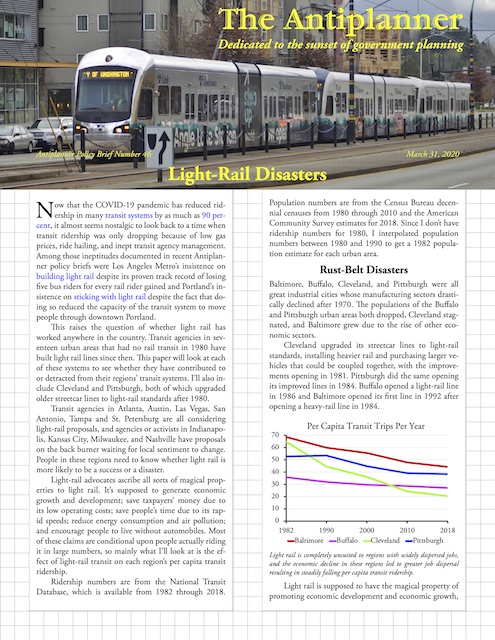

Now that the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced ridership in many transit systems by as much as 90 percent, it almost seems nostalgic to look back to a time when transit ridership was only dropping because of low gas prices, ride hailing, and inept transit agency management. Among those ineptitudes documented in recent Antiplanner policy briefs were Los Angeles Metro’s insistence on building light rail despite its proven track record of losing five bus riders for every rail rider gained and Portland’s insistence on sticking with light rail despite the fact that doing so reduced the capacity of the transit system to move people through downtown Portland.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

This raises the question of whether light rail has worked anywhere in the country. Transit agencies in seventeen urban areas that had no rail transit in 1980 have built light rail lines since then. This paper will look at each of these systems to see whether they have contributed to or detracted from their regions’ transit systems. I’ll also include Cleveland and Pittsburgh, both of which upgraded older streetcar lines to light-rail standards after 1980. Continue reading