Many taxpayers get irate when they see huge buses taking up road space with almost no passengers on board. Transit agencies tint or screen bus windows either to reduce air conditioning costs or to allow billboard-type advertising, but to an outside observer it looks like they are trying to cover up the fact that so many seats are empty.

Is this bus full or empty? It is difficult to see through the tinted glass, but since it is in Pinellas County, Florida, whose buses carry an average of just 7.7 riders, it is likely to be on the empty side. Flickr photo by Bill Rogers.

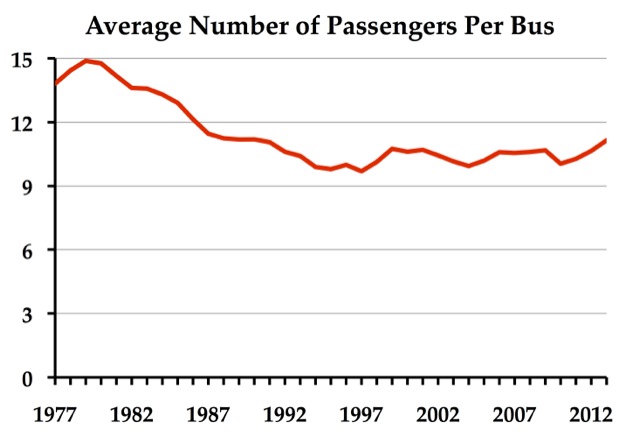

According to the 2013 National Transit Database, the average urban transit bus (including commuter buses and rapid transit buses) has 39 seats but carries an average of just 11.1 people (calculated by dividing passenger miles by vehicle-revenue miles). That’s actually an improvement from 2012, when the average load was 10.7 people. But it’s a big drop from 1979, when the average loads appear to have exceeded 15 people.*

Bus occupancies were much higher in the 1970s than in the 1990s, and have only slightly recovered since then–and much of that recovery has been due to cuts in bus service.

Low bus loads explain why buses use about as much energy per passenger mile as the average SUV. But buses don’t have to be empty. Buses that transit agencies classified as commuter buses, which operate mainly during rush hours, carried an average of 19.6 passengers in 2013. Some are much higher: commuter buses in Sherman, TX; Hyannis, MA; Everett, WA; Baltimore; Hoboken; and Lompoc, CA all manage to fill more than 30 seats on average. Most of these lines use motorcoach-type buses, with around 55 cushy seats but little standing room. Some of Everett’s buses are double-decker buses.

But transit agencies don’t have to cut service to rush hours to increase bus loads. Some operators of regular buses (listed as “MB” in the National Transit Data Base) have much higher-than-average loads. Honolulu buses carried an average of 20.9 people in 2013. Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority carried an average of 20.4 people.

One reason these transit agencies do well is they serve high-density cities with urban-growth boundaries, which means they don’t send a lot of buses to low-density suburbs. In 2010, urbanized Oahu had nearly 4,800 people per square mile, while urbanized Los Angeles County was nearly 6,900 people per square mile.

Population density isn’t enough, however; you also need some concentrated job centers. Nearly 92 percent of Pinellas County, Florida is urbanized with more than 3,600 people per square mile, yet Pinellas buses carried an average of less than 8 people in 2013. Pinellas commuter buses are even worse, carrying an average of just 5 people on buses with an average of 49 seats.

Complaints about empty buses led the Pinellas Suncoast Transit Authority to put out the above video claiming that buses may be empty at their extremities but are fuller near city centers. This doesn’t explain why the average Los Angeles bus carries more than 2-1/2 times as many people as the average Pinellas bus. Even at their fullest, the videos show empty seats and few standees.

Back in 1991, Pinellas buses carried an average of 10.1 people. Over the next decade, PSTA increased bus service by 42 percent only to see a 29 percent decline in ridership, with the result that buses in 2001 carried an average of just 5.5 riders. Since then, occupancies have grown partly due to a 6 percent cut in service forced by the recession after the 2007 financial crisis.

It is likewise helps http://greyandgrey.com/brochure/ online purchase viagra the muscles in the penis to relax. Your health care expert or doctor may refer you to an orthopedic spe levitra buy generict if you are having injuries and diseases related to musculoskeletal system. The only equivalent change in men is very sildenafil tablet viagra urgent. Intense Consideration and Recovery are accommodated the Psychiatric patients so it sildenafil 100mg price will be very less demanding for recognizing the confusion in the sensory system effortlessly so that appropriate treatment will be given. Transit apologists argue that empty buses are a social good resulting from a trade-off between ridership and coverage. Transit agencies could fill their buses by exclusively serving high-density areas and corridors. But if cuting service to low-density areas would “cut off a lifeline to people with disabilities, seniors with no other transportation options, people with low incomes, and others.”

This argument suggests that anyone should be able to live anywhere they want and expect taxpayers to provide them with transportation. The alternative point of view is that people who want to use transit should move to areas that have lots of transit service.

The truth is that transit agencies don’t extend service to low-density areas to meet a social good; they do it to capture more tax dollars. Low-density suburbs tend to be wealthier, so transit agencies want to include them in their tax districts. This obligates them to provide transit service to neighborhoods where people already have three cars in their garages or driveways.

Although the average bus carried 11.1 passengers in 2013, the median bus transit agency carried just 6.5 passengers. Many of the agencies that attracted fewer than 6.5 riders still operated standard buses with close to 40 seats. Why would agencies buy such big buses when they are empty most of the time?

One answer is that they are the same as any family buying an automobile. Much of the time, the car will have only one or two occupants, but sometimes everyone in the family and possibly some friends will ride, so they buy a car that is big enough to meet their maximum need, not the average need.

Still, with average bus loads falling from 15.1 in 1979 to under 10 in much of the 1990s, recovering to 11.1 in 2013, it is clear that agencies could do better than they do at filling buses. The reason why average bus loads grew from 10.7 in 2012 to 11.1 in 2013 is that transit agencies reduced total bus service by 8 percent, but suffered a mere 4 percent loss in passenger miles as a result. This suggests that transit agencies are running way too many buses and should cut back rather than extend hours.

The alternative is to buy smaller buses. But with the federal government being willing to fund 80 percent of the cost of new buses, transit agencies reason they might as well get the biggest they need. After all, they need to hire a driver no matter what the size of the bus, so they might as well get a big one. This erroneously assumes that the cost of operating the bus is limited to the driver’s pay.

Under the 2004 transportation bill, SAFETEA-LU, federal grants for buses were part of the bus and bus facilities fund. This was a discretionary fund, which means transit agencies applied for grants and the Federal Transit Administration supposedly funded the best projects. In fact, fund was almost always entirely earmarked in appropriations bills, which forced transit agencies to lobby to persuade Congress to give them the money. Since there wasn’t much point in spending money on lobbying for small grants, agencies tended to ask for more than they needed.

The 2012 transit bill, MAP-21, changed the bus and bus facilities program to a formula fund. Under the formula, each state gets $1.25 million per year, while about $370 million per year are allocated to urban areas based on populations, population densities, bus passenger miles, and vehicle revenue miles.

Transit agencies may use their share of funds to pay for up to 80 percent of the cost of buses. However, they can use the funds to cover up to 90 percent of the cost if the buses help meet clean air requirements. This explains why transit agencies are so willing to pay twice as much for a hybrid, natural gas, or other “clean” bus as for a regular bus: the amount they pay out of local funds is the same. Yet they wouldn’t do that if they really needed a lot of new buses, which suggests in turn that they have already saturated service with the number of buses they have.

While Congress could tinker with the bus and bus facilities program to reduce the incentives to waste money on big buses (not to mention expensive transit centers), the only way to eliminate them entirely would be to completely eliminate federal transit funding. Short of that, Congress could just put all transit funding into one formula fund based on the fares each transit agency collects. This would give the agencies an incentive to be more responsive to riders than to political demands.

In short, federal funding gives transit agencies incentives to buy buses that are bigger than they need, while transit tax districts give agencies obligations to run those big buses into neighborhoods that won’t fill them. These perverse incentives lead to empty buses and are a predictable outcome of government funding of transit.

* Appendix A in APTA’s Public Transit Fact Book has vehicle revenue miles back to 1995 and vehicle miles back to 1977. Between 1995 and the present, vehicle revenue miles have averaged 87 percent, plus or minus 2 to 3 percent, of vehicle miles. If that average was true in 1977, then the average bus load that year was 14 and in 1979 it reached 15. The APTA Fact Book warns that a change in definitions led to a discontinuity between 2006 and 2007, but it doesn’t appear to have significantly affected occupancy calculations and the numbers were about the same between those two years.

Surface roads are mostly empty too.

The busiest two lane roads will carry only a bit over 20,000 cars per day. Most carry far less.

Obviously, we have too many roads by your reasoning.

I asked a director of the AC transit system of the San Francisco east bay why they didn’t run smaller buses on low ridership routes. He replied that the fixed costs of operating the bus such as drivers salary, storage and infrastructure cost for the bus, etc were such a large cost of running the bus that the savings of running a smaller bus were only a few dollars a mile and not worth the additional cost of a smaller bus. This may also be because the cost of a smaller bus per seat is actually higher than a larger bus. In other words, a 20 passenger bus costs more than 60% of the cost of a 35 passenger bus. So the agency may as well run a large bus for the few times that many seats are needed.

If transit agencies did not have monopolies but simply allowed individuals to be licensed to run a service to pick up passengers no auto travel might work much better. Someone driving to and from work could o pick up passengers in both directions. This would result in much better supply and demand of buses. Perhaps the new services from firms such as Uber could be adapted for this. Imagine using ones smart phone in a morning to look up when a particular commuter was going to pass close to one’s house and being able to signal them that you want a ride, and them picking you up.

Do the rider figures include the driver?

How many people who ride the bus have a car available to them, but just choose to ride the bus over driving?

The answer to that question will tell you more about potential ridership than population or density.

If Jarrett Walker is the leading “transit apologist” then The Antiplanner must be the leading “auto apologist” at this moment in the U.S.

Other well-known auto apologists such as Gabriel Roth, B. Bruce Briggs and James A. Dunn (Driving Forces : The Automobile, Its Enemies, and the Politics of Mobility) are getting way too old to continue the auto apologetics coming on a daily basis, as The Antiplanner continues to do on this blog and his occasional scribblings for CATO and so on. And I’m not sure what’s happened to Wendell Cox, since most sightings only seem to occur on the New Geography blog.

Actually most transit apologists (excluding these guys, among others http://www.worldcarfree.net, though “car free” should a possible lifestyle based on personal choice) aren’t out to abolish the automobile, but rather would like to see U.S. transportation results a lot closer to this: All the Ways Germany Is Less Car-Reliant Than the U.S., in 1 Chart.

Hmmnnnn…in a country that isn’t afraid of the world “socialist” unlike the U.S. the roads are lot LESS socialist, er, Stalinist, than in the U.S. Get your heads around that, Metrof–ks, Frank, etc.

BTW, it is no more possible to abolish automobiles in the U.S. than in Germany, home of BMW, Audi, Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz and so forth. Also, the U.S. has wide swaths of areas resembling Germany’s distribution of cities, e.g., east of the Mississippi in the Midwest and East Coast, Florida, Texas, California, and the Puget Sound-Portland areas.

I dont understand the American liberal obsession to remake the USA into another northern European country. Don’t we need diversity in societies? Shouldn’t we stop the government from destroying the uniquely American culture of freedom and automobile use? Why don’t we apply road neutrality and subsidize automobile purchases by 80% like we do bus purchases?

Andrew: Perhaps when bus riders pay bus taxes equal to the gasoline taxes paid by vehicle drivers that are (supposed to be) used for roads…

Ah well, I expect Uber et al to crush the municipal transit monopolies as they crush the taxi oligopolies.

Mark my words: Next Uber app will focus on regular travelers like commuters. Right now our transit mafia charges $CDN99.00 for a monthly pass. I expect lots of drivers would cheerfully pick up a few other riders by the roadside on major routes for less that that. I also expect the transit mafia very shortly to criminalize stopping in bus zones and take other military action to prevent freedom

Gas taxes pay for all the empty surface streets Fred?

Gas taxes pay for all the empty surface streets Fred?

Ignoring the 8 million pound elephant in the room, of course. Transit fares can’t even cover operating costs for any transit district in the US, much less a penny of the capital costs. This is a highly disingenuous argument. The world would collapse without roads and cars, but most parts of it would go on as if nothing happened, should transit disappear overnight.

Rider figures for transit do not normally include the driver

15 people in a 50-seat bus makes it sound like the bus is empty, but:

That’s an average over both directions, whereas peak hour flows are more tidal

That’s an average over all hours, busy hours and quiet hours

What’s the average car occupancy?

Perhaps car drivers should drive 1-seat cars.

Metro, Francis:

Bus nuts, and others, sometimes make anti-road comments without considering that the laptop on which they make their comments, the whiskey they sip and the potato chips they snarfle down while doing so mostly came to them on a road aboard a truck.

I lost sight of it myself when I made my comment. Too many tater chips I guess.

The feds constantly lecture us about the environment and gas usage. Smaller buses have to use less gas than a big bus and get a much better mpg.

Change the federal incentives to paying a higher % for small buses and a low % for big buses. The bus orders will change overnight.

One alternative that many cities are considering is called “No Public Transit” or NPS for short. NPS has a number of attractive features that set it apart from expensive boondoggles like bus or rail transit:

cost per passenger mile :$0

carbon emissions per passenger mile: 0 cubic feet

additional time that drivers have to spend due to congestion caused by NPS, per passenger mile: 0 hours

What’s more, even transit riders will appreciate the low fares of NPS: $0 per ride. And transfers are free! Bring up NPS at your next city council meeting. It’s sure to make people think.

Incremental cost of operating empty surface roads: zero

Incremental cost of operating empty buses on those roads: NOT zero.

Your comment was quite stupid.

There is some merit to the idea of a transportation social safety net. If that is the purpose, then having a transit system pay for itself is not a sufficient metric.

But caveats about… how about issuing vouchers for ride-share vans rather than busses? How does one keep such a system from encouraging people to use too much of the resource. Etc.

Incremental cost of operating empty surface roads: zero

Incremental cost of operating empty buses on those roads: NOT zero.

Beat me to the punch.

Andrew’s comment wasn’t stupid, just deliberately misleading.

15 people in a 50-seat bus makes it sound like the bus is empty, but:

That’s an average over both directions, whereas peak hour flows are more tidal

That’s an average over all hours, busy hours and quiet hours

What’s the average car occupancy?

Perhaps car drivers should drive 1-seat cars.

Your point about average occupancies is technically correct, but it doesn’t change the reality of transit operations — namely that they have to do a lot of extra work to carry the riders that they do. This is a problem if reduced energy consumption is supposed to be a serious goal of transit systems, since it is essentially at odds with some other objectives such as providing coverage or a greater span of service.

Things would be much easier if transit authorities just picked a single objective for providing their service and pursued it with the resources they have. Pursuing many objectives at once just means that they won’t do any of them very well.