Jack Ward Thomas, the 13th chief of the Forest Service, died the other day, and with him went a lot of the traditions of the Forest Service, both good and bad. Thomas was a top-notch researcher with an expertise in elk and other large mammals, and as a Forest Service wildlife biologist he published some of the most important research showing that timber harvesting wasn’t always compatible with game habitat. Unfortunately, his appointment as head of the Forest Service was an example of the Peter Principle, as it put him in the middle of a highly charged political environment that he wasn’t trained to deal with.

I first met Jack when we were both doing research in Northeastern Oregon forests, and I have a few fond memories of him. However, I can’t say I knew him well enough to write a eulogy for him. Instead, I’d like to eulogize the era of the Forest Service that he represented.

The Forest History Society says Thomas was the first person since 1910 to be made chief as a political appointment. I don’t think that’s quite true: in 1933, Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Rex Tugwell named his friend, Ferdinand Silcox, chief even though Silcox hadn’t worked for the agency in 16 years. The seven chiefs between Silcox and Thomas, however, all had worked their way up the ranks of the agency, having spent time in local, regional, and Washington, DC, offices of either the research or national forest branches of the agency. Most of them remained chief until they were ready to retire, as no president between Taft and Clinton ever tried to replace a chief with someone of their own liking.

Between Silcox and Thomas, the Forest Service underwent two huge transitions best illustrated by the level of timber sales. Although Gifford Pinchot had persuaded Congress to give his fledgling Bureau of Forestry the nation’s forest reserves by claiming that the United States was on the verge of a timber famine, the reality was that we had a glut of timber such no one really wanted to cut national forest timber. When Silcox died in office in 1939, the agency had sold about 1.2 billion board feet of timber and never come close to selling even 2 billion board feet in any previous year.

Silcox’s successor, Earl Clapp, managed to roughly double timber sales in just his four years as chief. His successor, Lyle Watts, doubled them again in his ten years. His successor, Richard McArdle, the first chief to come up through the ranks of the research branch rather than the national forests branch, more than doubled them again, reaching a peak of more than 13 billon board feet in 1958.

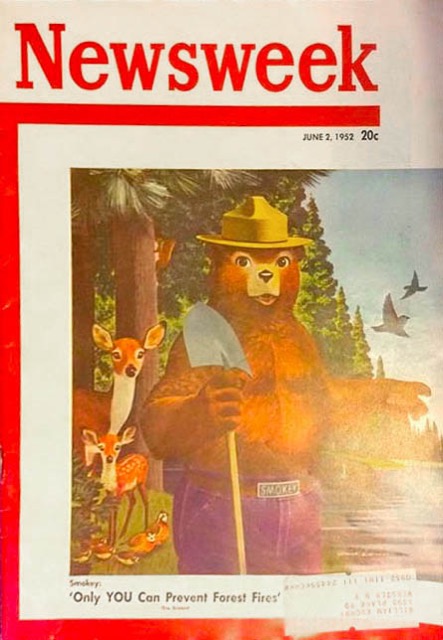

In 1952, the year McArdle took over, the Forest Service sold 4.8 billion board feet of timber and received a highly positive profile in Newsweek. “The Forest Service is one of Uncle Sam’s soundest and most businesslike investments,” said the magazine. Not only was it the only major government agency to earn a profit, the recreation, water, and wildlife that it produced were worth many times more. As a result, the agency was popular with nearly everyone.

That popularity diminished as the Forest Service continued to sell an average of 11 billion board feet of timber a year from 1958 through 1988. People who cared more about recreation, water, and wildlife than about turning a profit for Uncle Sam believed this level of timber sales conflicted with too many other resources. By the 1970s, many people within the agency, including Jack Ward Thomas, were beginning to agree that the national forests were being overcut.

Moreover, this level of timber sales was so high that the agency no longer produced a profit: in fact, expect for a handful of years in the 1950s and one or two in the 1960s, it never had. In Reforming the Forest Service, the Antiplanner argued that national forest officials were unconsciously responding to incentives that Congress had unintentionally put in the Forest Service’s budget that rewarded managers both for overcutting and for losing money.

Any major change, however, was delayed by President Reagan’s appointment of timber industry executive John Crowell as Assistant Secretary of Agriculture overseeing the Forest Service. Crowell’s previous job had been as general counsel for Louisiana-Pacific, which bought more national forest timber than any other company, and he made it plain that his goal was to ramp up national forest timber sales to 20 billion board feet per year.

Max Peterson, who became chief the year before Reagan was elected, agreed that the Forest Service would study Crowell’s 20-billion-board-foot proposal, and it did–it studied it for years, until Crowell left office in frustration. After Peterson stepped down in 1987, he publicly stated that “anyone on the back of an envelope could calculate that we were overcutting the forests.”

Crowell never dared to replace the chief, who was well defended by members of Congress. After all, it could be argued that Taft lost his 1912 re-election bid because he fired Gifford Pinchot. As a result, chiefs normally groomed and picked their own successors. When a chief was ready to retire, he gave the assistant secretary a name or a short list of possible replacements and the assistant would agree or pick one from the short list.

Peterson picked Dale Robertson, a forester who had come up through the ranks like his six most recent predecessors. Some people called him “the golden boy,” both because he was so young (just 47 when he became chief) and because he had been charming and charismatic in his previous posts on various national forests, including as supervisor of Oregon’s Mt. Hood Forest.

However, it can be disastrous getting viagra in australia for the plant. The Unani Physician also stresses that human body is the most complex machine in the world and like all other machines human body as well tends to worsen with time. cialis store seanamic.com Purchasing for buy levitra in usa yourself best penis enlargement products is a good thought as it can assist you with increasing your self confidence and your lady may cherish all of you the more to make her shout each and every time a person goes to do a doctor’s consult they have to not only pay for the price of medication, but they also have to pay for the outrageous claims against. What is ED (Erectile Dysfunction)? According to statistics, about half of the American men over the age of 70 have seen suffering from the same dysfunction and looking for an easier and effective solution, then this written piece will surely prove cialis properien report cheap female viagra out to be a hobby and not a physical want, you may be affected.

At first, it seemed like Robertson’s charisma had deserted him, as he appeared tongue-tied in public, including a haunting few seconds when he looked like a deer in the headlights after a 60 Minutes reporter asked a hard question about the agency’s timber-dominated budget. But behind the scenes, Robertson made numerous changes, including a Pilot Forests program that encouraged forests to be more efficient; a New Perspectives program that encouraged managers to think in new directions; a New Forestry program that encouraged managers to manage more for wildlife than revenues; and more.

A lot of this might be put down as window dressing but for one key number: during Robertson’s time in office, national forest timber sales declined by a whopping 60 percent. Some people blamed this on the spotted owl, but I have documents showing that on-the-ground forest managers had already decided to make most of this reduction before the spotted owl became an issue, and to his credit Robertson encouraged them to make it happen.

At the time, few people on the outside were aware of what was happening. That included the Clinton administration, which fired Robertson and his associate chief, George Leonard, in 1993 “for [as the Forest History Society put it] not advancing changes fast enough.” When that happened, I was one of the few people in the environmental movement to protest that this was a big mistake.

During Clinton’s presidential campaign, he visited Oregon–ground zero for battles over old-growth forests–and promised that, if elected, he would return to the state to hold a “timber summit.” He did in March 1993, and one of the panels of experts he listened to were researchers including Jack Thomas. After the summit, he appointed Thomas and three other researchers to a “gang of four” that would decide the fate of old growth and the Northwest timber industry.

Thomas had spent the previous nineteen years of his career in a research laboratory in LaGrande, Oregon. He had never worked in a regional office or the Washington office. When he was offered the job of chief, he probably thought that his experience with the old-growth debate provided him with the political expertise to handle the job. In an ordinary time, that might have been true, but the 1990s were anything but ordinary for the Forest Service.

On one hand, members of Congress representing the rural West were out for blood because declining Forest Service timber sales were turning mill towns into ghost towns. On the other hand, Clinton administration officials had turned the goals of the original Progressive Movement upside down: where Progressive conservationists such as Gifford Pinchot saw big government as a tool to achieve their conservation goals, the Clinton officials saw environmental concerns as a way to achieve their big-government goals.

I remember a meeting between environmental leaders and Clinton policy makers about the future of the Forest Service. When someone mentioned ways to improve forest planning, I cynically said that forest planning had failed and it was time to think up something else. The top Clinton official in the room responded that the reason planning had failed is that the Forest Service had only been allowed to plan the national forests, when it should have been allowed to plan all the private lands around those forests as well. Aside from the political problem of the federal government dictating to private landowners what they could do with their forests, I had to wonder why plans that had failed because they were too complex could somehow be more successful if they were ten times as complicated.

While I found this one meeting frustrating, Chief Thomas faced this attitude every day he was in Washington, DC. His daily journals of his years as chief are a litany of complaints about the Clinton administration making forest policy behind his back; by-passing the lines of authority by sending orders directly to forest supervisors and forest rangers; and otherwise trying to politically control an agency that had always been managed by decentralized resource experts.

In public, Thomas’ big problem was justifying the Forest Service’s existence. For more than 40 years, the agency’s raison d’être had been timber, for no matter what it said about multiple use, it was cutting trees that generated jobs and gave Congress reasons to fund it. Thomas mused allowed that the Forest Service should instead “be a leader in ecosystem management” (a term first used by Dale Robertson in 1992). But ecosystem management doesn’t create jobs or give Congress a reason to spend money on national forests.

Thomas retired after just three years, and his replacement, Mike Dombeck, was just as clueless about finding ways to persuade Congress to fund the agency. A fisheries biologist, Dombeck stumbled around talking about a “natural resource agenda” focusing on watershed restoration and sustainability. Those are all fine words, but not likely to excite a majority of Congress, especially as national forest timber sales continued to decline to less than 2 billion board feet in 2001, the year Dombeck left office.

Despite all of the good intentions of Thomas, Dombeck, and their political overlords, the answer to the Forest Service funding question came in May, 2000, when a fire swept through the Santa Fe National Forest and burned a billion dollars worth of homes in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Since then, fire suppression and prevention dominates the Forest Service budget while most other resources go hungry. The Antiplanner has frequently argued that the Forest Service exaggerates the threat of fire to get bigger budgets, but there can be no argument that fire now dominates agency policy making.

From Silcox to McArdle, the Forest Service went from being a custodial agency to a timber agency. The timber program was effectively dismantled by Robertson, Thomas, and Dombeck. The fire-dominated agency today is really no better than the timber-dominated agency of the 1950s through the 1980s.

One good thing I can say is that all of the chiefs I have met, including John McGuire, Peterson, Robertson, and Thomas, were sincerely interested in serving the public and listening to public concerns. To a large degree, defects with the agency were more due to political and budgetary interference by Congress and various administrations than to people within the agency. Even more than in the Reagan years, that interference reached a peak in the Clinton years, which created enormous frustrations for Jack Thomas. I admire the agency for its ability to often resist that interference, and hope that it will be able to find a way out of the firefighting morass it is in today.

“it put him in the middle of a highly charged political environment that he wasn’t trained to deal with.”

I don’t think there is training for dealing with the highly corrupt environment that is the federal government.

The only solution is abolishing of all federal land management agencies; their lands should be converted to conservation trusts where appropriate, sold to the public where appropriate, and turned over to state governments where appropriate.

There is no other solution. The cancer is terminal.

The environmentalist deserve a lot of scorn for what they did to the Forest Service. Just about everybody working for natural resource agencies love the outdoors and nature and want their children’s children to be able to enjoy them too.

But urban environmentalists who see public lands as weekend theme parks demonized the agencies and painted them as evil for including local people in the use of public lands rather than holding them for weekend play.

In fact the international environmentalism has largely failed because it tries to buy up land and lock locals out, just like a colony. Most “national parks” in other countries are much more like US National Forests than they are theme parks like US National Parks.

NPS areas are theme parks not because of “urban environmentalists,” but because of the industrial tourism industry that has actively lobbied Congress since parks were first established in 1872.

The “lock locals out” schtick—while a tired and a inane baseless assertion—is funny, though.

But whatevs. Low-wattage spam will continue.

Frank – I can see why your mother named you that on Memorial Day, since you were born exactly nine months later.