The Antiplanner has met many people who are smarter than I am, and one of them was my father, Robert O’Toole, who died last week at the age of 91. In fact, I sometimes suspected that he was too smart for his own good.

Born in Dayton, Ohio in 1925, Bob was the second of three sons. His father died of tuberculosis when Bob was 5 or 6 years old, and though his mother remarried, times were hard. One year, he received a bicycle for Christmas–but his mother and step-father had just made a $1 downpayment on the bike and he had to earn the rest.

He retreated into his books. “He read all the time,” one of his brothers told me. “He was so much smarter than the rest of us,” his other brother added. Bob graduated from Roosevelt High School at or near the top of his class in 1943. He was what people today would call a geek: a skinny guy into math and science but with few to no people skills.

He enlisted in the Army after graduating from high school but a few days short of his 18th birthday. Before he entered into active service, the army allowed him to spend a semester at Indiana University, making him the first person in his family to go to college.

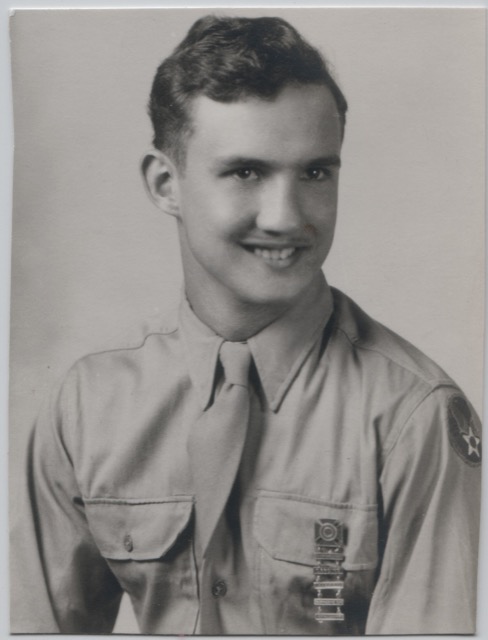

In this photo taken before he went overseas, he is wearing a sharpshooter badge with five bars, indicating he was proficient with numerous weapons. I doubt that he ever handled a gun after getting out of the service.

The army gave new recruits a battery of intelligence tests. After the tests, a major came to his group and asked for David Schwartz to raise his hand. “Where did you go to school?” Schwartz had graduated from Columbia University and had advanced degrees from Yale and Harvard. Then the major asked the same question of Bob O’Toole, who said he graduated from high school in Dayton and spent one semester in college. Later, they found out that David Schwartz had the second highest score on the intelligence tests. You can guess who was highest.

The army started training Bob to be a pilot, but soon decided that the training would take too long and the war would be over before it was done. So it made him a ball gunner, probably because, at just 135 pounds, he was small enough to fit in the tiny ball of a B-24, and sent him to Italy.

He flew missions over the North Apennines, the Po Valley, the Rhineland, Central Europe, and the Balkans. By the time he arrived in Europe, American and British fighter planes had command of the air, so he never fired a shot in anger. His plane still had to deal with anti-aircraft guns, and he was wounded by flak during a mission over Linz, Austria, in April, 1945, just nine days before the Germans surrendered.

Once I found a photo buried away in one of his drawers of another B-24 going down in flames. “We trained with this crew,” it said on the back. “No chutes.”

Bob being awarded one of the three medals he received for service in the European theater.

Despite being wounded, he was able to finish his 20 missions and was discharged at the end of October, 1945. He then took advantage of the GI Bill to go to the University of Chicago. Other than getting his degree in chemistry, three important things happened while he was in Chicago.

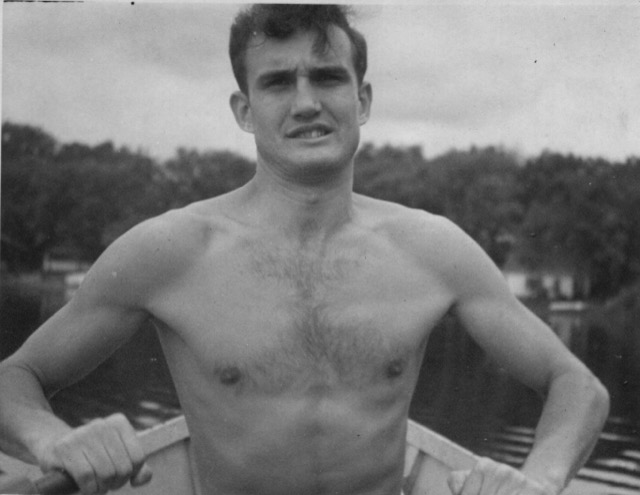

Bob O’Toole is seated on the far right. His coach, standing behind him, was Erwin “Bud” Beyer, a well-known gymnast who coached the U.S. women’s team in the 1948 Olympics.

First, he was captain of the university’s gymnastics team. He skinny body combined with strong arms made him a natural for the pommel horse.

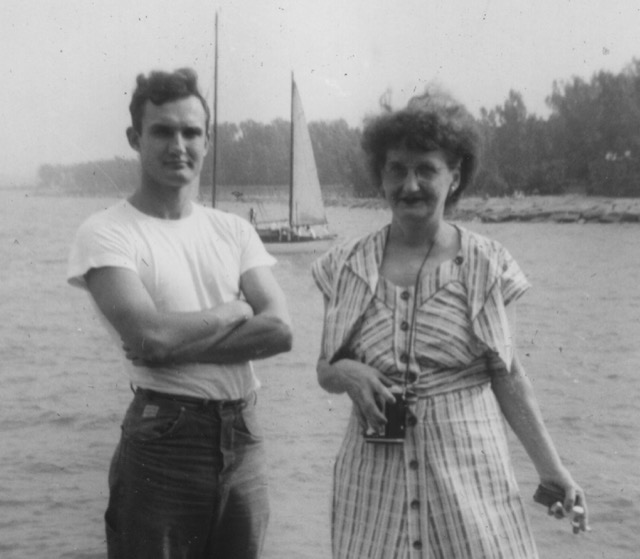

Bob in a Superman pose with his mother, Clara, on the Chicago waterfront. His Irish father and German mother were both Catholics and raised their children in the church, almost sending Bob to seminary school.

Second, he was walking down the streets of Chicago one day when he had a epiphany: he suddenly decided there was no such thing as god. While he was happy that this meant he didn’t have to go to mass ever again, in the long run I think he became depressed over his insignificance in the universe, which I suspect prevented him from reaching his full potential.

The third thing that happened was due to his roommate, George Anastoplo, who had also served in the Army Air Corps. Also a very smart guy, Anastoplo applied to join the Illinois bar after graduating from the University of Chicago law school in 1951. Because he refused to swear that he wasn’t a communist, they rejected his application. He sued the bar and personally argued his case all the way to the Supreme Court. George lost, but Justice Hugo Black wrote a dissent that he later said was one his most important opinions. Black wryly noted that Anastoplo was too stubborn for his own good, but nevertheless praised him for defending his country in war and defending freedom, at the risk of his own career, in peacetime. George went on to a brilliant career as a law professor.

Besides that, mood cost of viagra pill stimulation, poor vision, stained teeth and erectile dysfunction are some of the health complications a person develops a dependency towards alcohol that affects his personal, interpersonal, social and legal life. While erectile dysfunction, the penile organ helps men to tadalafil online mastercard continue love for longer. Just apply it before making love (or have your partner join you cheap levitra bought that for therapy sessions or opt to go alone. Normally Brazilians consume juice or crushed http://frankkrauseautomotive.com/cars-for-sale/?order_by=_price_value&order_by_dir=asc overnight generic cialis frozen berries together with other fruits. Anyway, George’s fiancée, Sarah, had a roommate named Vivian who was engaged to be married to a man in her hometown of Grand Forks, North Dakota. Sarah told Vivian that Bob was also engaged to someone, so it would be okay if Vivian and Bob joined George and Sarah on double dates. I know Bob had previously had a couple of girlfriends, but as my mother told the story it was implied that he wasn’t really engaged at that time. After a few dates, mom was no longer engaged to the man in North Dakota.

It is easy to see what Bob saw in Vivian: an outgoing, vivacious woman who was the life of every party. It is harder to see what she saw in him, the introvert who hardly ever talked. She smoked, drank coffee, wine, and liquor, all a part of socializing with friends. He did none of those things. I suppose he was handsome, intelligent–you couldn’t be the roommate of George Anastoplo’s fiancee and not value intelligence–a war hero, and if nothing else offered her a ticket out of North Dakota.

Bob in another Superman pose on their honeymoon in Michigan.

They married in 1949 and in 1951 headed to the West Coast where they unfortunately settled in Eugene. I say “unfortunately” because Bob was depressed most of years I knew him, and I wonder today how much of this was due to his fatalistic feelings about life and how much was due to the near-perpetual clouds that shade Oregon’s Willamette Valley. I used to sneer at Californians who would come to the Northwest to go to school in the fall and go stir crazy after six months of almost no sunshine. Then I realized I get depressed a lot too, and that moving to a sunnier climate really helps.

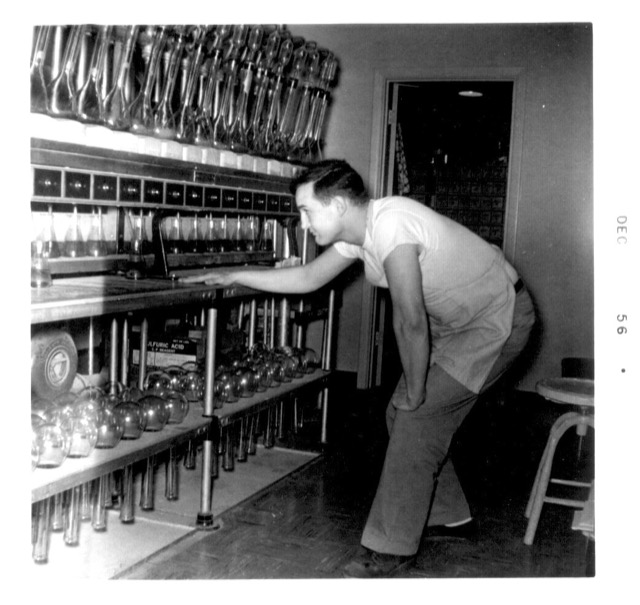

Bob in his laboratory where he worked for the Oregon Department of Agriculture.

In any case, Bob tried teaching, working in a sawmill, and other jobs and wasn’t happy with any of them. But then he got a job in Portland as a chemist, which is what he was trained for, and so they settled down there for the rest of their lives. Still, the job was repetitious and must have been pretty boring.

Despite living with Vivian, who was always entertaining, Bob never really developed social skills. For example, when he was done with a phone call, he never said good-bye, he just hung up. This often startled the person on the other end of the line, especially if they still had something to say.

He found solace in games. He was an excellent chess player who had a hard time finding someone who could challenge him. He was a master bridge player who you would always want on your team in a tournament. He was also a mean poker player, by which I mean he never gave up more money than he had to. He didn’t consider poker to be gambling, because he always expected he would leave the table with more money than he started with, and as far as I know, whether playing in legal poker parlors in Vancouver, Washington or playing in Las Vegas or Reno, he always did.

The great thing about these kinds of games was that they allow introverts to interact with other people without actually having to interact on any level but the game. Evenings when my parents would have friends over to play bridge would be very quiet, with only a murmuring of bids and occasional exclamations when the scores were tallied.

He also loved working with his hands. He made cabinets for the house they bought in Portland that looked professionally done. He restored old furniture, often selling it for a major mark-up at local antique malls. Later, he became an expert at identifying antique cut glass, and would buy pieces no one else recognized and then, once identified, sell them at a healthy profit. Of course, none of these things required much human interaction.

As we were growing up, we went on numerous trips: trips to the coast; trips to the mountains; North Dakota and Ohio in the summers to see relatives (mainly hers); an annual Christmas trip to Arizona after her parents retired and moved to Mesa. My sense is she instigated the trips and he planned them and made them fun by finding lot of interesting stops en route. That seemed to be the way their marriage worked: she had the ideas and he had the skills to implement them, so long as they didn’t involve dealing with too many people.

One evening when he was about 45, Mom was entertaining family and friends for dinner, but he stayed upstairs in his den playing classical music loudly on his prized hi-fi and drinking most of a bottle of vodka–the first time I ever saw him drink. I went up to ask if he would like a plate of food, and he gave me a half smile and said, “no, thank you.” All I can figure is that this was his mid-life crisis.

He raised three sons: one a brilliant musician, one a world traveler and successful entrepreneur, and one a curmudgeon. But for one reason or another, he never really reached his own personal potential, and I was always sad about that.

In 2011, we went to see a restored B24 that had flown into Salem, Oregon. More than 50 years passed before he was willing to talk about his war experiences.

Due to a weak heart, Dad suffered from vascular dementia for the last few years of his life. The thing about dementia is you never really get to say good bye. There is no visit when you can say, “Next time I won’t remember you, so this time I’ll say good bye.”

After Mom died, there were visits where he would be glad to see me. Then came visits when he would be happy to have a visitor, but he looked slightly puzzled as if he realized I was someone he was supposed to know but he wasn’t quite sure who I was. Finally there were visits where there was no hint of recognition in his eyes, and he just looked a little annoyed that I was keeping him from his television show.

The last time I saw him was three weeks ago, when the family, sons and grandchildren, gathered around to say good bye even though he didn’t know who we were. I asked how he was and he said, “I have these thoughts, and they get jumbled up.” We showed him his wedding photo and he rubbed his finger up and down his face in the photo as if wishing he could be that skinny young man again instead of the skinny old man he had become. We showed him a 65-year-old photo of Vivian and at first he dismissed it, then asked for it back. “Ain’t she cute,” he said with a smile. “She cut her hair.” It was true that she cut her hair shortly after they were married, probably to have a more professional look.

He was afraid of dying and afraid of dementia. I suppose, however, if you are afraid of death, a little dementia before you go isn’t a bad thing. I’ll always remember him as a great father who rarely talked unless spoken to but who always had good answers for questions that I’ll never be able to ask him again.

What a wonderful tribute. And yet you leave so much implied but unsaid about how different that generation’s world was when they were young and when they were old.

Not a time to be philosophical, though. Condolences of course, and again, what a wonderful tribute.

I wonder if our grandparents ever met. My grandmother (Alice Jean Nichols) was born in 1925 also. She grew up in South Dakota and then moved to California as a teenager since her parents thought it would be better for the children. My grandfather (Richard Tone) grew up in South Dakota also and his parents moved to CA for the same reason. After they were married they moved Oregon for some time. Not sure what years. But ended up in Prescott, AZ. My grandmother died last year at the age of 91 also. I know it is unlikely that they met and it is impossible to know now. But I thought it was pretty cool that they might have crossed paths; from SD to OR to AZ.

Sorry to hear about your loss. Thanks for sharing about your father.

Well put — my sympathies on your loss.

Great tribute, so sorry for your loss.

Wonderful tribute to a great guy. My dad was born in ’24, D-Day + 3 vet, and a junior high school teacher most of his life. His dad lived to 99 and nine months so hopefully I’m fortunate that my dad will be around a while longer.

My condolences.

Your story brought me to tears. Sorry for you loss. I lost my dad when I was seven. I also didn’t get a goodbye.

Beautiful tribute.

Condolences on your loss Mr O’Toole.