Someone responded to my Baptists & bootleggers post by asking if I really had to mention the rape. The answer is “yes,” and not just because Wonkette started a trend of bloggers putting a sexual spin on all political news.

The Neil Goldschmidt story, including the statutory rape, is important because it shows how a Baptist became a bootlegger, and how everyone–the media, leading politicians, business leaders–continued to pretend he was a Baptist until the revelation of the rape came out. Only then did the media reveal to the public what a few had suspected all along: that all the stories of Portland’s light-rail utopia were merely a cover for a taxpayer-subsidized real-estate con.

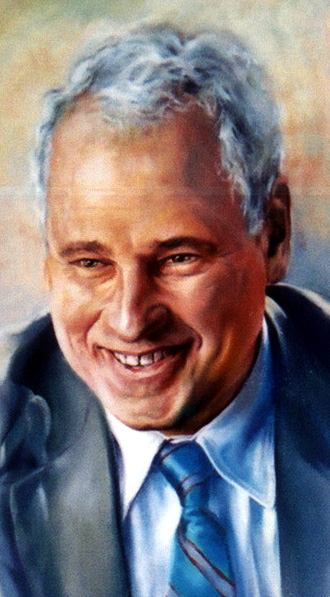

As I mentioned in my Vanishing Automobile update about Goldschmidt, Portland spin doctors are already trying to rewrite history, crediting the city’s light-rail vision to the late Governor Tom McCall. But McCall left office long before the crucial decisions were made about light rail.

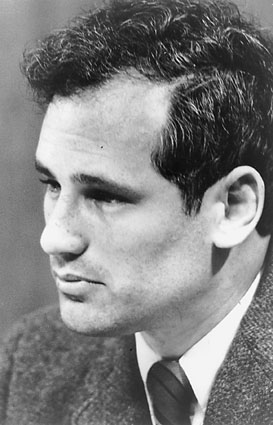

Goldschmidt, the real father of Portland’s light-rail system, was elected to the city council as a reform candidate in 1966. As a fledgling Nader’s Raider, I briefly worked with City Commissioner Goldschmidt’s office writing a proposal for transit improvements in 1972. This plan called for a demand-responsive bus system that could vary its route to pick people up and drop them off wherever they wanted. Such a system would have low capital costs, but high operating costs (though no higher than any other bus system), so it was never implemented for the general public. It could have been much more effective than anything Portland has now.

Two years later, Goldschmidt created a dilemma when he persuaded the city council to cancel an interstate freeway in east Portland. Congress allowed cities to spend the federal dollars from cancelled freeways on transit–but only on capital improvements, not operating costs. This ruled out a demand-responsive bus system. Instead, Goldschmidt turned to light rail, not because it was efficient but precisely because it was expensive and could consume all of those federal dollars. Thus, the very inefficiency of light-rail technology made it Portland’s preferred solution.

While Goldschmidt was making these decisions, I was going to graduate school at the University of Oregon and working for environmental groups that were trying to save wilderness areas in Oregon’s national forests. One of those environmental groups put on an Earth Week environmental teach-in every April, and in 1978 they invited former U. of O. student body president and current Mayor Goldschmidt to speak about the environment.

I was a bit stunned when Goldschmidt told the audience of wilderness advocates that he was not in favor of protecting wilderness. Instead, he thought we should make cities more livable so that people would not need to go out into the wilderness. He added that Portland was zoned for nearly three times its then-current population, and he thought more people should live in Portland instead of building in the suburbs.

In 1979, Goldschmidt became the U.S. Secretary of Transportation. Then he came home and was elected governor in 1986. In 1990, he left office and started a political consulting firm. He was soon arranging deals such as no-bid contracts for Bechtel to build a light-rail line and hundreds of millions of dollars in subsidies to real estate developers who built on the light-rail lines.

In 1998, Portland’s Willamette Week newspaper observed that Goldschmidt once used his influence “on behalf of the city, the state and the nation. Now he’s shaping the civic landscape for his corporate clients.” But no one paid much heed until 2004, when Willamette Week revealed that, when he was mayor in the 1970s, Goldschmidt started a sexual relationship with a fourteen-year-old girl that lasted for three years.

Only then did newspapers such as the Portland Tribune start reporting about the light-rail mafia that was controlling much of the region’s land-use and transportation planning. Without the rape revelation, most Portlanders never would have known that the Baptist had become a bootlegger and that their taxes were making his friends rich.

I often visit cities that are contemplating rail transit and hearing stories about how Portland’s rail lines have stimulated all kinds of development. The stories never mention that the developments were all subsidized and, rail or no rail, would not have been built without the subsidies. Most of these cities will not be lucky enough to have a Goldschmidt-style sex scandal, so their taxpayers will never know where all their money went.

Pingback: » The Antiplanner