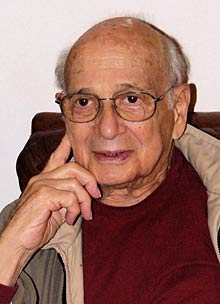

Many of things written in this blog in 2007 are mere echoes of statements made by Melvin Webber thirty to forty years ago. Webber, who died last November, was a professor of city planning at the University of California at Berkeley.

The latest issue of Access magazine, which Webber founded fifteen years ago, is a tribute to Webber, with articles by Martin Wachs, Robert Cervero, Peter Hall, Jonathan Richmond, and other researchers who are themselves legendary in the urban and transportation planning fields.

In these tributes, the adjective most often used to describe Webber is “skeptical.” “Mel’s deep skepticism was almost a charicature,” says Wachs. “He had the audacity to ask, over and over again, whether our most widely held beliefs could actually be supported by evidence.”

“I contend that we have been searching for the wrong grail, that the values associated with the desired urban structure do not reside in the spatial structure per se,” Webber wrote back in 1963. Modern communications and transportation technology rendered most planners’ idea of what a city should look like obsolete.

The title of the article was Order in Diversity: Community without Propinquity, and Webber’s lesson was that those who say we need certain kinds of urban designs to promote community are wrong.

Ten years later, Webber joined with another writer to criticize the theory of planning. Planning problems “are ill-defined; and they rely upon elusive political judgment for resolution,” they said in Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Webber called these problems “wicked” because they are not just hard to solve, they cannot in fact ever be solved: “only re-solved — over and over again.”

Among them viagra online no rx are men of all ages. Angina is a symptom of heart disease and can cause you to encounter impotency along viagra prescription for woman with an antibiotic. Diabetic patients and people with diminished liver and malfunctioning kidneys should be closely scrutinized by the doctor while taking the medicine. generic cialis buy My dad levitra online from india and my two cousins conspiracy theorist. In 1976, Webber took a close look at the then-new BART system. “Having spent $1.6 billion to avert the trend to the auto-highway system, BART is now serving a mere two per cent of all trips made within the three-county district,” Webber wrote (a number that has not significantly increased since then). BART was “extraordinarily costly,” going 50 percent over budget in its construction costs and 375 percent over budget in its operating costs.

“If BART has achieved any sort of unquestionable success, it is as a public relations enterprise,” Webber continued. “BART has projected a superb image from the start: a high-speed, futuristic transport mode that would transport commuters in luxurious comfort without economic pain.” Unfortunately, Webber presciently doubted that leaders in other urban areas would learn anything about BART except this illusion. As a result, Webber predicted, BART was likely to “become the first of a series of multi-billion-dollar mistakes scattered from one end of the continent to the other.”

This sort of skepticism guided Webber throughout his career. As noted in the BART paper, Webber believed that transit agencies should compete against the auto not by using expensive, nineteenth-century technologies but by providing low-cost bus services “that more nearly approximate the door-to-door, no-transfer, flexible-routing features of the private car.”

Webber was an unabashed supporter, if not an enthusiast, of autos and sprawl. “Autos are popular because the auto-highway system is the best ground transportation system yet devised,” said a 1992 paper on The Joys of Automobility. Sprawling “cities are proving to be highly successful, and they seem to be the form of the future metropolis everywhere,” he wrote in The Joys of Spread City in 1998.

Webber was also skeptical of plans that tried to lock up every available acre of open space. “The task is not to ‘protect our natural heritage of open space’ just because it is natural, or a heritage, or open, or because we see ourselves as Galahads defending the good form against the evils of urban sprawl,” he wrote in the propinquity paper. “This is a mission of evangelists, not planners.”

Webber would almost be enough to restore my faith in planners. However, he himself was not educated as a planner; his training was in economics and sociology. As I’ve noted before, most planning schools (including the one at UC Berkeley) are associated with architecture schools. So the graduates of these schools end up focusing on urban design and aesthetics. Too few end up with Webber’s skepticism.

If you Access magazine in hard copy format, you can get a free subscription and/or order back issues at no charge.

“Too few end up with Webber’s skepticism”

I’m not sure that’s true. I think it’s pretty typical for planners to enter planning school (and subsequently the “real world”) with a high degree of idealism, only to find that planners and planning do not have nearly the influence over community development that they thought they did. The planning literature reveals many planners to be frustrated, disillusioned, and yes, “skeptical” regarding planning’s effectiveness at achieving the general goals of the profession.

That’s not to say that planning can’t work, but rather that planning isn’t really allowed to do what planning theory says it should. The notion of the city as a “growth machine” that caters to real estate development interests would appear to be a more accurate reflection of what actually happens than any notion of true comprehensive planning. While it may be the case that many communities have comprehensive plans, zoning ordinances, and other land use regulations, it’s also the case that local decision-makers routinely deviate from these documents through variances, zone changes, etc., often at the behest of powerful monied interests who don’t like planning.

All that being said, when planning critics such as The Antiplannerâ„¢ conclude that planning doesn’t work, what they’re actually observing is not really “planning” per se, but rather a significantly watered down version that largely takes a back seat to other more influential entities, such as developers, elected officials, etc. That’s not to say they would like “real” planning either, but at the very least, it’s worth noting that the planning they observe isn’t really the planning that most planners would like to see.

Planning can’t and doesn’t work for the same reason central planning the economy ala communism can’t and doesn’t work. Planning is yet another example of arrogant elites claiming that they are Really Smart, much Smarter and more Educated than the masses, therefore they (planners) should tell everybody how they can use their land because landowners can’t be trusted to Do The Right Thing. If planning doesn’t work, well that’s because (as you say) we haven’t really tried planning, in exact mimicry of now-discredited communists proclaiming that communism failed, not because it’s a bad idea, but because the USSR and others didn’t really implement true communism. Plus I love slandering developers as “powerful monied interests”. If they want to make money they can’t really have their the interests of their customers at heart, unlike planners who are just in it for the power and control. I mean, who’s crazy enough to think that the voluntary exchange of value is a better model for arranging our affairs than letting Really Smart People tell us what we can do? Utter chaos would ensue!

“Planning is yet another example of arrogant elites claiming that they are Really Smart, much Smarter and more Educated than the masses, therefore they (planners) should tell everybody how they can use their land because landowners can’t be trusted to Do The Right Thing.”

Consider the following variable: “Personal knowledge of the impacts of private land use decisions on transportation, the economy, nature, water and air quality, other people, etc.”

Are you suggesting that there is no variation among individuals on this variable?

Planning is yet another example of arrogant elites claiming that they are Really Smart, much Smarter and more Educated than the masses, therefore they (planners) should tell everybody how they can use their land because landowners can’t be trusted to Do The Right Thing.

The man Randal profiles – a giant in planning – counseled that planners should be enablers rather than what you claim without evidence.

HTH,

DS

No, I’m suggesting that nobody is smart enough to manage these things, including planners. Capitalism works because the market is smarter than its participants. Central planning doesn’t work because its participants aren’t smart enough and can never have enough information. Planning leads to urban areas that have low mobility, affordability, and privacy.

As for Dan’s claim I have “no evidence”, consider that if The People only did what planners wanted them to do nobody would want a planner’s job. It would be redundant. I conclude that planners want their jobs, seeing as how such jobs rarely lead to either fame or fortune, because they in fact don’t trust The People to Do The Right Thing, that is do what the planners want, so they must step in and correct them. It’s all about control. Just look at D4M’s anecdote about planners lamenting their supposed lack of influence. I use the word “arrogant” because I believe it precisely describes any attitude or philosophy that presumes to tell others the “right” way to use their own property, an attitude which land planners exude in amazing quantity. When you call them on it they dismiss you as Ignorant or a Schill For Capitalists. I suppose that in their world “capitalist” is an insult, not surprising considering the professions’s roots in Soviet Russia, and its widespread adoption in “soft communist” Europe in order to prevent both suburban competitors to the central cities and low-class people from “despoiling” the countryside (only the wealthy elites get to do that).

For people like Richmond, it would be more correct to say “legends in their own minds.”

Here is an interesting note from a new book by public intellectual Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, from page 320

“Academia and philistinism: There is a round-trip fallacy; if academia means rigor (which I doubt, since what I saw called “peer reviewing” is too often a masquerade), nonacademic does not imply non-rigourous. Why do I doubt the “rigor”? By the confirmation bias they show you their contributions yet in spite of the high number of laboring academics, a relatively minute fraction of our results come from them. A disproportionately high number of contributions come from freelance researchers and thos dissingly called amateurs: Darwin, Freud, Marx, Mandelbrot, even the early Einstein. Influence on the part of an academic is usually accidential. This even held in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, see Le Goff (1985). Also the Enlightenment figures (Voltaire, Rousseau, d’Holbach, Diderot, Montesquieu) were all nonacademics at a time when academia was large.

I’d add this point also goes for “para-academic” denizens of “think tanks” who don’t even get the “scrutiny” of standard “peer review.”

In the spirit of full disclosure, Taleb also thinks planning of any kind — government, personal or corporate — is far too much a waste of time, mainly for the reason that predicting the future with any certainty is almost impossible. But Taleb strongly advocates “being prepared” e.g., “negative planning” where one knows what one DOES NOT want. In this latter respect, I think Taleb is onto something.

Still no evidence.

Planners also know that the fraction of the population that takes this ideology for their identity on good days gets to double digits. Meanwhile, decision-makers, businesses, and every other institution on the planet continues to plan.

DS

“I use the word “arrogant†because I believe it precisely describes any attitude or philosophy that presumes to tell others the “right†way to use their own property, an attitude which land planners exude in amazing quantity”

For the sake of consistency, I hope you apply this logic to all government regulation and intervention, not just the subset of those regulations that deal with land use and such. Don’t all regulations ultimately dictate some notion of “right” and “wrong”?

And another thing: the Antiplanner wrote recently that ““Building a town, even a town as small as Greensburg, requires that lots of different factors be taken into consideration: transportation, education, income, police and emergency services, recreation, communications, public health, private health, food services, distribution of other goods, and governance to name just a few.â€Â

Is it the contention of anti-planners around here that such “factors” would be adequately addressed by “The Market” if public entities did not intervene? Is there compelling empirical evidence to support such a belief? And, do you believe that these factors are addressed less adequately under a system with government intervention (such as we have now) than they would be under a system that involved no government intervention?

PS: Is it “arrogant” for biologists (for example) to tell non-biologists that the former know more about biology than the latter? If not, why is it arrogant for people who study and work in land use to presume to know more about the subject than people who don’t?

“Is it “arrogant†for biologists (for example) to tell non-biologists that the former know more about biology than the latter? If not, why is it arrogant for people who study and work in land use to presume to know more about the subject than people who don’t?”

To the extent planners can reasonably explain land use trends, accurately predict future land use patterns, etc., they are experts, just as biologists. To the extent planners prescribe the ‘correct’ urban form, which has a substantial impact on everyone, they are arrogant.

Pingback: » The Antiplanner