The latest estimates say that Denver’s FasTracks rail projects are only $1.5 billion overbudget, not the $1.8 billion originally reported. The $300 million savings comes from such things as single-tracking light-rail lines that were originally planned to be double tracked.

Denver’s Regional Transit District (RTD) plans to make up the $1.5 billion by selling $800 million more bonds (thus making for a longer pay-back period), and asking the federal government for more money. But officials still expect a $400 million or so shortfall.

One way RTD hopes to close the gap is through “public-private partnerships,” which the local press is misleadingly calling “privatizing.” The idea is that, instead of having RTD design, build, and operate the rail lines, they would turn most of that over to a private company. Of course, the company would still need huge subsidies, but RTD hopes it can save some money this way.

This whole process raises all sorts of questions in my mind.

- Under the original financial plan, RTD would complete construction in 2017 and pay back the loans and bonds by 2048. Since rail lines need to be rebuilt every 30 years, they would need to borrow more money to rebuild the lines as soon as the original bonds were paid back. Under the new plan, it will take several more years to pay back the bonds, which means they will still be paying them off after the rail lines are fully depreciated. Do they expect voters will agree to another tax increase to keep the lines going even while they are still paying a tax for the fully depreciated line?

- RTD says it can single-track part of one of the rail lines without reducing service. If so, why didn’t it plan to build a single-track line in the first place?

- Similarly, if public-private partnerships can save so much money, why didn’t RTD propose them in the first place?

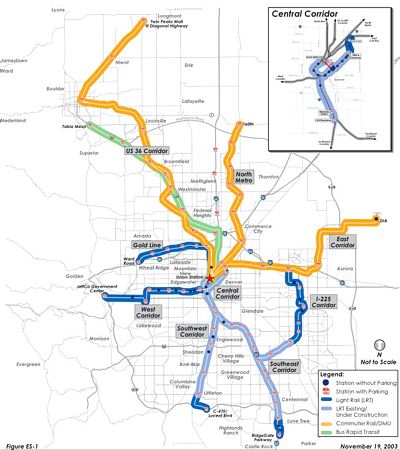

Yellow lines were supposed to be Diesel-powered commuter trains; blue lines were supposed to be light rail; green is a bus-rapid transit route. Light blue is existing light-rail lines.

RTD’s problem is that it has to carefully balance construction to all parts of the region. The political compromise that led to passage of the tax increase required that RTD build lines to all major suburbs simultaneously. Each of the suburbs feared that, if they were last on the list to have a rail line, cost overruns would kill their project. So they demanded simultaneous rather than sequential construction of the rail lines.

All of the “major investment studies” done for the planned routes found that rail transit was the least-cost effective way of moving people and reducing congestion. For example, in the East Corridor, as shown in the table below, rail both costs more and does less to relieve congestion than new freeway or high-occupancy vehicle lanes.

Cost Per Hour Saved

Cap Cost Op Cost Annualized Hours $/Hour

New fwy lanes $305 $16 $40 18.3 $2.18

HOV/bus lanes 337 15 42 12.6 3.34

Diesel rail 374 34 63 8.9 7.12

Electric rail 571 29 75 9.1 8.26

Capital and operating costs are in millions. Annualized cost, also in millions, is the sum of operating costs and amortized capital costs. Hours is the annual number of hours saved to commuters in millions. $/hour is the cost per hour saved.

At the time of the election, RTD had decided to operate Diesel commuter trains in the East Corridor. But it has since switched to electric trains even though this would cost more. In fact, the total capital cost of the East Corridor line is now well over a billion dollars, or roughly twice as much as projected in the major investment study.

Officials from west-side suburbs are angry that their lines are being short-changed with single tracks when RTD is spending more on the East line. It does seem perplexing.

My hypothesis is that, given a choice, transit agency officials will always go for the high-cost solution. They view taxpayers as a bottomless pit of funds and see no need to restrain their spending. Someone must have noticed that Diesel commuter trains were more cost effective than electric trains and switched.

It is easier to come back later and double track a single-tracked line than it is to convert a Diesel-powered line to electric power. So RTD probably figures to spend as much up front on the high-cost technology. That sounds cynical, but when it comes to rail transit, no matter how cynical you are, you can’t keep up.

After all, one of the pre-FasTracks light-rail lines that opened a few months ago is carrying only a handful of people each trip. While RTD says it will cut service on this line (which goes from nowhere to nowhere), you have to wonder why they thought it made sense in the first place. The answer is that rail transit isn’t about transportation; it’s about construction jobs.

One factor that may play a role in the decision to electrify the East line is campaign contributions. The prime candidate for making Diesel-powered railcars is Colorado Railcar, while Siemens, a German company, makes many of the electric-powered railcars in use today. Siemens contributed over $100,000 to the FasTracks campaign, while Colorado Railcar contributed only $20,000.

Perhaps the switch from Diesel to electric is payback. Colorado Railcar will still get to sell its Diesel cars for the Boulder-Longmont and North Metro lines, but Siemens will get most of the rest of the system.

I suspect Colorado Railcar, whose one contribution came just a few days before the election, assumed that it had a home advantage and would not have to contribute much to get the contracts. Or maybe it just didn’t have Siemens’ deep pockets. Siemens’ first contribution came more than four months before the election. In trouble over a bribery scandal, the company obviously has no compunction about greasing the right palms to get contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

I’m new around here, so maybe my initial impressions are incorrect. But from what I’ve seen, The Antiplanner typically files any kind of non-automobile transportation story under “Planning Disasters”. I’m not sure that’s necessarily fair.

Why is building rail transit “planning”, and why is building roads “not planning”?

It also seems to me that The Antiplanner considers “going over budget and taking longer than expected” to be a unique feature of rail projects, and assigns the blame to “planning”. Are we really supposed to believe that road building projects (and construction projects in general) don’t commonly go over budget and take longer than expected? I don’t have personal experience with contractors, but my impression from friends and family is that contractors “Always take longer than they say they’re gonna take, and often go over budget”. That may be an exaggeration, but I don’t buy that these problems are unique to rail.

Yeah, he really should just be criticizing the massive cost per passenger mile. It costs many times that of driving when you include building costs. See http://www.portlandfacts.com/Transit/Cost-Cars-Transit(2005).htm

Our commuter rail is projected to come in at over $1.70 per passenger-mile (before cost over-runs!). That his over EIGHT times the national average cost of driving. IBID

Of course, in Portland they had a slight cost over-run too. See http://www.portlandfacts.com/Transit/WestOnTimeOnBudget.htm

The main advantage of rail is that it sucks up transportation funds, so that there is little money left for roads, so that those evil citizens, will waste more time in traffic congestion.

Thanks

JK

Who is responsible for construction projects (whether rail or otherwise) costing more and taking longer than expected? Are these projects generally built by “government”, or are they generally built by the private sector? The Antiplanner gives the impression that “planning” and “government” are responsible, but if the projects are built by private contractors, it seems to me that they are at least partially responsible, aren’t they?

The Denver RTD project is primarily over budget due to steel prices being so high (~70% of overrun, IIRC) and from scope creep (add-ons to project).

Therefore, see, it is the planner’s fault and thus the ‘Planning Disaster’ hyperbole.

DS

D4P,

According to a study published in the Journal of the American Planning Association, U.S. rail projects go an average of 41 percent overbudget while U.S. road projects go an average of just 8 percent overbudget. Another study by the same authors found that rail projects tend to overestimate ridership while road projects tend to underestimate use.

This is a planning issue, I contend, because such overruns and underforecasts are a predictable result of comprehensive, long-range planning. The fact that steel prices are up does not excuse the planners, who put hundreds of millions of dollars into the budget for “contingencies.” Instead, it only shows the absurdity of trying to plan a megaproject that will take more than 13 years to design and build.

Overruns for rail projects are typically far greater than roads, but for what? Roads serve everyone. Rail serves a few percent — on a good day. The cost of FasTracks was $4.1 billion. That was $8.1 billion with interest. Now its 6.5 billion cost, before it even has the opportunity to run into the first unforeseen glitch in construction, will notch that up a couple of billion. Building FasTracks was projected to make a .5 percent difference in cars on the road in 2025 overall, and move an additional whopping 1.4 percent off the road in peak hours. But without a doubt, some people think they’re worth it.

Thanks, Antiplanner. You said: “such overruns and underforecasts are a predictable result of comprehensive, long-range planning”. It sounds like your standard for evaluating the success of long-range planning is unrealistically high. I doubt anyone, planner or otherwise, believes they can predict the future with perfect accuracy. At some level, the purpose of long-range planning isn’t to perfectly predict the future, but rather to make some effort to prepare for the future and to coordinate contemporary decision-making in a better fashion than would be achieved if no such efforts were undertaken at all.

If you want to argue that that kind of planning is somehow not worth the effort, that’s one thing. But to essentially argue that long-range planning is pointless because there is typically some divergence between the future that was predicted and the future that actually happens seems to impose too stringent a standard.

Nice joke line:

Instead, it only shows the absurdity of trying to plan a megaproject that will take more than 13 years to design and build.

All that planning that went on for the Bureau of Reclamation’s water projects that populated the West? Absurd. All that planning for the Interstate Highway System? Absurd. Hoover Dam? LOL.

Randal, I don’t have to think of comedy lines when you write. Thank you for saving me the work. When partisans at, say, RMN point to the fine work of “the economist” (sic), I’ll just send them the link to your comment above.

DS

They’re saying the East Corridor will now cost $2 billion (March 5, 2009)

http://www.eastcorridor.com/alternatives.html