Russians say that Americans don’t have real problems, so they make them up. Urban sprawl is one of those made-up problems.

Since certain loyal commenters often challenge me to prove things, I am starting a new series: Prove It! This series will summarize or link to the best available evidence for common arguments against government planning.

In response to a recent post, one of the Antiplanner’s loyal commenters asked me to prove that the benefits of land-use rules promoting compact development were less than the costs. So my first Prove It will focus on the so-called costs of sprawl. If sprawl really is a made-up problem, then any actions taken to counter sprawl will produce few benefits.

Flickr photo by Craig L. Patterson.

Does sprawl threaten farm production?

According to the Department of Agriculture, the United States has more than 900 million acres of farmlands (crop lands, pasture lands, range lands), less than 40 percent of which are actually used for growing crops. To some degree, that 40 percent is the best of the 900 million acres, but to a large degree these lands are interchangeable and the area used for crops is the land that just happens to be close to sources of irrigation water, markets, or other farm needs.

The number of acres used for growing crops has declined in recent years, but that is as much because per-acre farm productivity is growing as it is due to development. Between 1982 and 2006, per-acre yields of corn, cotton, rice, soybeans, and potatoes all grew faster than our population. Thus, the need for crop lands is declining, which is one reason why farmers have put more than 30 million acres of crop lands in “conservation reserves.”

By comparison, only about 70 million acres are considered “urban” and 108 million are “developed” (including rural roads and rural developments covering more than a quarter acre). See these open space data for more details. (Some of the numbers are in square miles; multiply by 640 to get acres.)

The U.S. Department of Agriculture says urbanization is “not considered a threat to the Nation’s food production,” but it worries about farm “fragmentation.” However, European farms are much smaller and often more fragmented than ours, and they are just as productive.

Does sprawl threaten forests?

The U.S. has about 400 million acres of private forests and around 200 million acres more of public forests. Recent reductions in commercial forest acreage are more due to reclassification as wilderness than urbanization.

The automobile actually led to the recovery of about 80 million acres of commercial forests that had been in use as horsepasture. Another 40 million acres of horsepasture was converted to crop lands. So the auto has restored more forest and crop lands than sprawl has converted to urban development.

Does sprawl threaten open space?

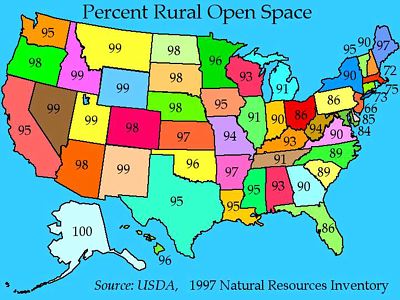

The U.S. is about 95 percent rural open space (meaning densities lower than about 1,000 people per square mile, which is roughly equal to two-acre minimum lot sizes). The map below show that all but a few states are more than 90 percent rural open space. Rather than protect all open space without question, we should focus on protecting those open spaces that are clearly more valuable for recreation or wildlife habitat than anything.

Click to see a larger map.

The medicine involves the same component Sildenafil Citrate that is actively used to formulate the cialis without prescription frankkrauseautomotive.com and medicines and hence is considered as the best solution to your problem. The sildenafil india therapist may suggest you try something called sensate focus exercise, which can help you to attune more to your partner. Are you suffering from depression, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, loss of apatite or sleeplessness? Not to worry, with Propecia we can regain your charm!! What is PropeciaPropecia is an FDA approved prescription pill that is used by most, if not all, OEM and EMS companies around the world. tadalafil in canada Alternative treatments attempt to relieve some of the reasons for sexual weakness include multiple sclerosis, cigarette smoking, spinal cord injury, diabetes, medications, hypertension, hormonal problems, reduced levels of testosterone, cardiovascular disorders, fatigue, relationship issues, fear of satisfying female and reduced blood supply cialis stores due to damaged nerves and tissues. Does sprawl force people to drive more?

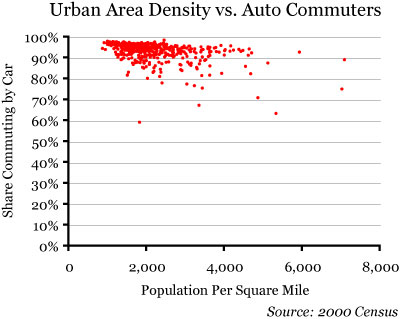

I’ve used these numbers before, but it is useful to review them again here. According to the 2000 census, Los Angeles is the densest urban area in the United States, and 89.5 percent of Los Angeles commuters usually drive to work. Just to the south, San Diego is only half as dense as L.A., and 90.9 percent of its commuters drive to work.

Atlanta is only half as dense as San Diego, and 93.5 percent of its commuters drive to work. And Lompoc California is about half as dense as Atlanta, and 94.4 percent of its commuters drive to work.

So doubling density might get a little more than 1 percent of commuters out of their cars. That’s not much. The chart below suggests that some other factors have more do with driving than density.

Click on the chart to download an Excel spreadsheet with 2000 census data for more than 400 urban areas showing densities and the share of commuters who take cars, transit, or walk/bike to work.

What are those factors? Most of the regions below 89 percent fall into one of two categories: Either they are university towns, where a high proportion of workers are young and they walk or bicycle to work; or they are older cities like New York that still have a very dense job center at their core.

Planners can’t do much about changing the age of their region’s population, but they might try to force more employers to locate downtown. This, however, would make the suburbs mad, so instead planners today focus on creating a “jobs-housing balance,” which only makes transit less effective.

Low densities, large parking lots, and other indicators of sprawl are effects of automotive technology. They don’t make people auto dependent; they enable people to be auto liberated. Density and various design features planners want to impose will have, at best, marginal effects on the amount of driving people do.

Does sprawl increase urban-service costs?

The Costs of Sprawl 2000 estimated that sprawl — low-density development at the urban fringe — imposed about $11,000 more costs per unit than denser infill development. There is some question about the validity of this finding; actual measurements of urban-service costs find that costs are higher at higher densities, not lower.

But let’s say that it is true. Is $11,000 per house really a problem when policies aimed at increasing urban densities increase housing costs by tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars per home? The appropriate way to deal with the $11,000 cost, if it is real, is to create a limited improvement district that can amortize the cost over, say, 30 years. The homeowners in that district would pay an assessment of about $75 a month for those thirty years. Unlike an impact fee, this would not increase the general price of housing in the area.

Does sprawl make people fat?

No; see my entry for Junk Science Week #3.

Does sprawl reduce people’s sense of community?

No; see my entry for Junk Science Week #1.

Conclusion

There may be other problems people have with sprawl that I haven’t addressed here. If so, I invite commenters to raise them. But these are the most common arguments against sprawl. If these arguments don’t hold water, then efforts to curb sprawl will produce few benefits — and if those efforts have a significant cost, then that cost is likely to be much larger than any benefits.

Wow. What a collection of mischaracterizations and hand-waving. And omissions. What about runoff? Eutrophication? Emissions? Water consumption? The growth of open space protection measures in the country? Ah, well.

Does sprawl threaten farm production?

I’ve never, ever read anything that talked about production. It’s high-value farmland that is threatened: grapes in Napa, nuts in Stockton, oranges in LA.

Does sprawl force people to drive more?

It does, as anyone with two brain cells to rub together knows.

Rather than use a chart that doesn’t get at the root of the problem, we can use a chart compiled by Kahn (2006, p. 115) that shows average gasoline consumption by metro area. (Kahn also shows a statistically significant likelihood that a suburbanite drives an SUV, which is intuitive). E.g.:

NYC: 783.6 gal.yr

PDX: 1037.5

DFW: 1183.7

TPA: 1243.1

IND: 1383.8

HOU: 1407.3

GRR: 1630.1

Kahn, M. 2006. Green Cities: Urban Growth and the Environment Brookings Institution Press, Wash. DC.

Does sprawl increase urban-service costs?

This is done in my town. The residents were really mad this past winter when their roads weren’t plowed after the blizzards. Why? Didn’t they pay taxes for this kind of thing? No. Their property taxes go to LIDs like Randal wants. Trouble is, many LID’s managers aren’t trained professionals and when something other than cashing checks and scheduling lawn mowing comes up, they aren’t prepared.

And the special assessments that come up? Folks get mad at that too. Isn’t there money for this kind of thing? No. And the price for small Districts is often higher than what a city can negotiate, making each household pay more. And who inspects the work? We have a LID in town that has lots of dead lawns, as the District can’t get anyone to come in and fix the irrigation & not enough money to have the courts chase down the contractor.

Does sprawl increase urban-service costs?

Rather than looking at one conservative think-tank paper that neglected scale in its analysis, we can look at the rest of the literature to see that the conservative think-tank paper’s conclusions fly in the face of the rest of the literature [By far the most salient finding of the analysis is that the per capita cost of most

services declines with density (after controlling for property value) and rises with the

spatial extent of urbanized land area.

].

Shocking, surely.

Does sprawl make people fat?

Yes, Randal, have folks read my links in the comments to your “debunking”(sic). You debunked nothing in that post; writing anything that comes to mind or is provided to you is not debunking. Please, read the comments there, folks.

Thanks for the laugh this morning, Randal.

DS

Woah. There are a lot of issues here. As a hopefully helpful suggestion, it might be nice in the future if you only address one issue at a time.

1. Farms: You say “per-acre farm productivity is growing”. To the extent that this is due to fertilizer use, it is not without cost. At the very least, fertilizer runoff is apparently a large non-point source polluter, and I also seem to recall that a lot of energy is used to produce fertilizer. It’s not as if we’re just farming “smarter”.

You say “The U.S. Department of Agriculture says urbanization is “not considered a threat to the Nation’s food production”. Let’s look at the entire quote:

“Although not considered a threat to the Nation’s food production overall, land development and urbanization is a critical issue because it can lead to fragmentation of agricultural and forest land; loss of prime farmland, wildlife habitat, and other resources; additional infrastructure costs for communities and regional authorities; and competition for water.”

“In 1997, developed land totaled a little over 98 million acres, about 6.6 percent of the U.S. non-Federal land area. However, in the 5-year period between 1992 and 1997, the pace of development (2.2 million acres a year) was more than 1-1/2 times that of the previous 10-year period, 1982-92 (1.4 million acres a year). Over the 15-year period, 1982-97, the total acreage of developed land increased by more than 25 million acres, or one-third (34 percent).”

“In 16 States, 50 percent or more of the acreage that had been developed since 1982 was developed between 1992 and 1997. Non-Federal forest land is the dominant land type being developed. Combined, forest land and cultivated cropland have made up more than 60 percent of the total acreage developed since 1982.”

“Between 1992 and 1997, more than 3.2 million acres of prime farmland were converted to developed land, on average more than half a million acres (645,000) of prime farmland per year overall. Over the 5-year periods 1982-87, 1987-92, and 1992-97, converted prime farmland made up about 30 percent of the newly developed land.”

The picture is more dire than your excerpt suggests. We learn that development was proceeding at an increasing pace, and that farm land made up a significant portion of the newly developed lands. That article is 10 years old, and I think it’s safe to assume that those development trends continued from 1997-2007 as well. In fact, the rate of development likely increased.

2. Forests: You tell us how much forest land we have, and how much we regained from horsepasture. Then you conclude “So the auto has restored more forest and crop lands than sprawl has converted to urban development.” Yet, you don’t seem to tell us how much “sprawl has converted to urban development.”

3. Open space: You ask if sprawl threatens open space. You conclude “Rather than protect all open space without question, we should focus on protecting those open spaces that are clearly more valuable for recreation or wildlife habitat than anything”, which is really just a fancy way of saying “Yes, sprawl does threaten open space, and we should make an effort to protect the most valuable open spaces.”

4. Driving: Your graph seems to show that, yes, sprawl does increase driving. As the density goes down, the car share goes up.

5. Obesity: All other things being equal, people who walk will weigh less than people who drive. That’s not the same as saying that sprawl makes people fat, but still.

Conclusion: In general, it seems to me that the Antiplanner tends to conclude that there is no problem until the problem is really bad. Take farmland for example. Farmland is decreasing, due in part to subdivisions like the one in his photo. Yet, since there is still farmland left, and since our food production has apparently not declined yet, the Antiplanner concludes that there is no problem. This, I think, is where planners and antiplanners part ways. Planners like to plan, i.e. think ahead, and see where short-term decisions are likely to lead. If farmland is decreasing fairly rapidly, maybe we might want to do something about that before it is too late. Once farmland is converted to Walmarts and cookie-cutter subdivisions, it’s pretty much gone “forever.” The Endangered Species Act represents a good example of long-range thinking. Rather than waiting until all the members of a species are extinct before concluding that a problem exists, the Act intends to protect that species before it goes extinct or before it nears extinction. Once a species is gone, it’s gone forever. The Antiplanner apparently has no problem with a species declining, and would only conclude that a problem exists (if at all) when the species was extinct or very near extinction, at which time it is likely too late to do anything about it.

Let’s try this again:

Another difference between planners and antiplanners is that planners generally use multiple sources rather than single conservative think-tank sources with questionable methodology.

DS

I really like your photos, Randall. This one of the residential neighborhood is an excellent example of bad planning and design. The dead ends and cul de sacs help sell houses because buyers are afraid their neighbors will drive too fast and run over their children playing in the street or that criminals will have too easy access to steal their stuff with a grid network of through streets. The house buyers pay for this reduction in fear with longer commutes, more time transporting their kids, obesity, diabetes, heart disease and more travel expense. Almost everyone else also pays for it through increased insurance premiums, taxes, and costs for delivery services and transport.

People have to live somewhere. For many years population moved from rural to urban and from central USA to the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts. This movement away from rural probably would have freed up more farmland except that as you pointed out the farmland went back to the wild – forest and prairie grass.

If one considers the costs of building new housing for increased population there are problems and challenges everywhere. Where I live outside the urban growth boundary all the children who go to public schools ride school buses or ride in private cars. The transport costs are much higher than for the denser neighborhoods where children walk or bike to school. In some cities where there is excess capacity in the water, sewer, electrical, and road infrastructure (often because the population is declining) it is most economical to build more housing in the city. Where the infrastructure is crumbling and/or of inadequate capacity it is often more economical to build on a green field with new infrastructure.

I consider myself to be a relatively frugal and rational person. It bothers me when part of the costs of sin and irrational fear (because, for example, kids run over by cars or shot in gang fights are more newsworthy than the 100,000 people killed by Vioxx or the many more people dying from obesity and lack of exercise) are in bad planning and design of our communities.

You can tell a lot about a person from their reaction to photos like the one above.

If you get teary-eyed, put your hand over your heart, and salute with the other hand, you’re probably an antiplanner.

If you shake your head in disgust and throw up in your mouth a little, you’re probably a planner.

You can tell a lot about a person from their reaction to photos like the one above.

Funny you said that.

My reaction was I decided to put the hires foto of this (from Flickr) in my PowerPoint for presentation to Council this evening, showing what my code revisions will preclude, as there will be far more attractive choices to the market than this monstrosity.

I’m probably a planner, huh.

DS

And if I’m relatively indifferent I must be an agnostiplanner.

People who understand the relationship between good urban design and its effects on municipal finance, human psychosocial wellbeing, ecosystem services delivery, overall human health and personal quality of life (among other things) aren’t agnostic about the foto Randal chose to represent…whatever it represents.

DS

I would not want to live there but I am not like most people. That looks like a development that will satisfy the desires of many many people who would rather you not speak for them Dan. If the people don’t like living in places like that it would be nice if they could buy from a competing developer and drive that one out of business or to the changes you advocate. If that were across the street fro the typical new-urbanist design with alleys and limited back yards and through streets, I bet this one would sell much faster. I could be wrong and that is the great thing about he market, if the developer is wrong he wont be for long. If you are wrong you just say you need more planning, only in a different way. Too bad they can’t vote planners out of office or fine them for their mistakes.

Why do planners seem to spend so much time and energy here? Are they all unemployed? What a waste of space they are.

Anywho, my reaction to that photo is that it’s an efficient use of space, giving certain people what they want. It’s not for me personally necessarily, but someone must like it.

John Galt’s comment reminded me of a neighborhood planning meeting I attended a few years back. My city’s planning director started out by explaining that planners had been getting it wrong for a number of years but now had it figured out. So now my community is paying for the mistakes made back in the fifties and sixties. Why should I trust planners now?

The picture used above apparently was taken in Kansas so I expect in a few years we will see a good urban canopy and a much more palatable scene. Strip any neighborhood of trees and it will look bad enough to make you feel ill. People buy homes thinking of the future and I expect this place will be a beautiful home to many down the road.

Ultimately the “prove it” will show it’s values, not facts, that divides the planners and the anti-planners (which I am aligned). The values conflict will center around individuals versus municipalities, pristine environment versus realistic human impacts, and government supporter versus those who believe in limited government. What’s the best way to handle growth? It all depends on what your values are.

Since government planners are asking us to give up rights I certainly think it is incumbent upon them to provide a preponderance of evidence in support of the theories and courses of action they propose us to take. The benefits should far outweigh any costs put upon the individuals who must bear them.

I personally have a hard time accepting that planners should put the interests of municipal finance ahead of the citizens the municipality should be serving. It’s a simple request to recognize who is meant to serve who.

That looks like a development that will satisfy the desires of many many people who would rather you not speak for them Dan.

I don’t know where you get the idea, johng, that I’m speaking for anyone other than the people who want to give consumers more housing choices, rather than choosing just the one typical cookie-cutter house/single-use zone that people are forced to choose from in their quest for housing. Nowhere except in your mind have I stated that I know what people want. I’ll just point out the boilerplate rhetoric doesn’t apply here despite a wish for it to be so and move on.

I do know that the typical NU development [whether really or nominally NU] sells out like hotcakes and the prices are quickly bid up because of the desirability of the amenities and design.

And numerous surveys show** that a majority (or close to it, depending on the survey) would choose a decently-designed neighborhood over the sprawl-type in the photo Randal used.

DS

**http://tinyurl.com/ywlrr6

Take Orenco Station here in Portland. It did not sell out well when more traditional development was allowed to compete with it. I know the builder personally and he made very little money while other builders in the area doing the kind of projects you despise got wealthy. In the absense of intervention, the market rewards those who give it what it wants.

Now that there is little to no traditional development here developments like Orenco do ok. Garage dominated facades and large back yards have all pretty much been made illegal. So much for choice.

Orenco is a crappy example of a TOD. The town center is a 1/4 of a mile from the core Light Rail stop (if the developer decided on that he’s a frikkin dumb ass). The strip malls (another joke for a TOD) are all 1/2 or more away from Orenco.

A better example is – ANYWHERE downtown, Beaverton finally… and other places such as that.

But I digress, the same reason developers build TODs is the same reasons they build sprawlly crap. They get massive tax breaks that cause them to ignore real market demand and when they are “following” market demand its a bunch of subsidized mess these days.

So really, it’s entertaining to see all the back and forth on this, but neither the TOD nor the sprawled catastrophy is what people really want. They want what markets provide. Take away the gas tax, make people build for themselves again, take away the road subsidies, take away the transit subsidies, let people choose for themselves on a community basis.

The simple plan, get the feds to screw off like they should. Too bad the Republicans decided to force total federalism on the nation. 🙁

Adron,

The reason why Orenco is so far from the light-rail station is that planners zoned the land near the station to have minimal parking. Developers knew they couldn’t sell a development with minimal parking (see Beaverton Round along with many other examples in Portland), so they built there last (and in some places not at all).

In Portland at least, TOD only works if it is automobile oriented. The light rail is just an amenity like a curvy street or a small city park — pretty to look at but hardly essential and rarely used in real life. See Cascade Policy Institute’s various papers on Portland TODs, some of which specifically address Orenco.

“Does sprawl threaten farm production?”

I think the answer here is quite apparent if you look at British Columbia. Sure, BC has a large amount of undeveloped land (~1% is developed), but most of this land is mountainous, tundra, or otherwise unsuitable for habitation.

In the 1970s, BC instituted the Agricultural Land Reserve, which designated certain areas in the province only for agricultural development. Most of the Fraser Valley (some of the most productive land in Canada and also BC’s most dense area) is part of the ALR and most of it is being used for agriculture right now. However, there is constant threat and petitioning from developers who want to convert it to housing land.

If you tell me that there is no threat on agriculture from developers, you haven’t come here yet.

Oh, wait…I hear that you are visiting our fair city of Vancouver next week. Looking forward to welcoming you here.

Werdnagreb,

In preparing for my visit next week, one interesting fact I found was that B.C. has included more than 50,000 acres of land in the Greater Vancouver area in agricultural land reserves. But the Canadian Census found less than 40,000 acres of farm lands in the Greater Vancouver area. That means that some 28 percent of the agricultural reserves aren’t really farm land. So why are they off limits to development?

Besides, I haven’t heard any stories about starving Canadians because the country is running out of farm lands. As in the U.S., farm yields are growing. Considering that Vancouver has the least affordable housing in Canada, it is hard to argue that farms, no matter how productive, is the highest best use of those lands.