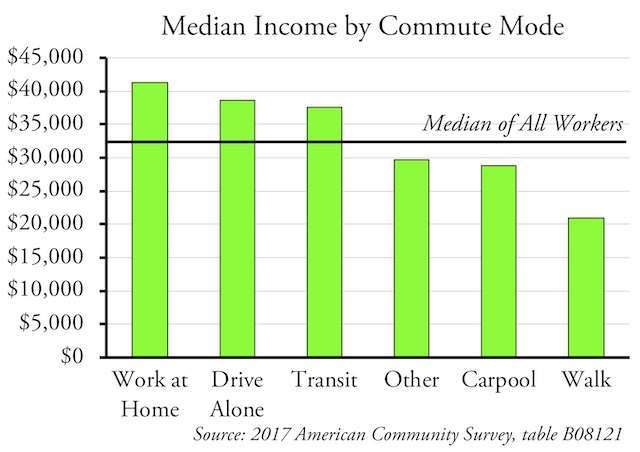

The Census Bureau’s 2017 American Community Survey revealed that, for the first time since the Census Bureau began keeping track of such data in 1960, the median income of transit commuters has risen above the median income of all American workers.

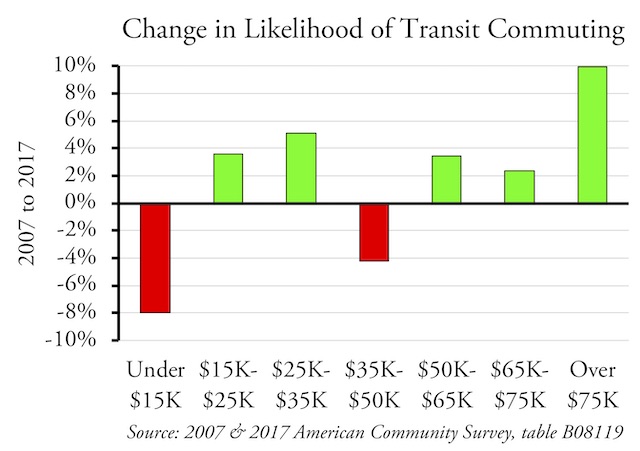

One reason transit commuter incomes have risen is that low-income transit riders are giving up on transit. Thanks to a growing economy, the number of people who earn less than $15,000 a year has declined, but the number of transit commuters who are in that income bracket has declined even faster, so that low-income commuters are 8 percent less likely to use transit than they were a decade ago. Meanwhile, people earning more than $75,000 a year were 10 percent more likely to commute by transit in 2017 than in 2007.

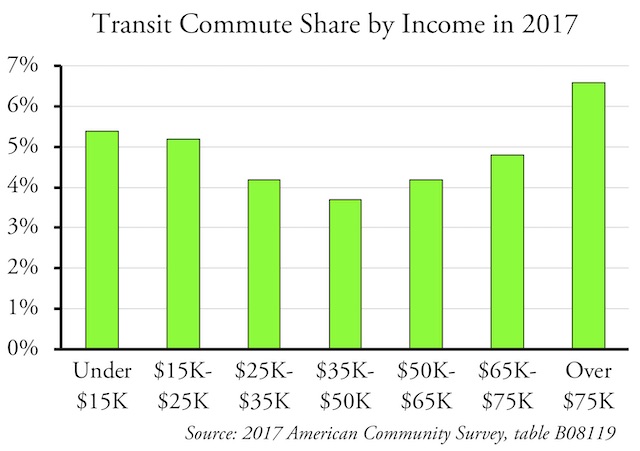

By 2017, people who earned more than $75,000 a year were considerably more likely to take transit to work than people in any other income bracket.

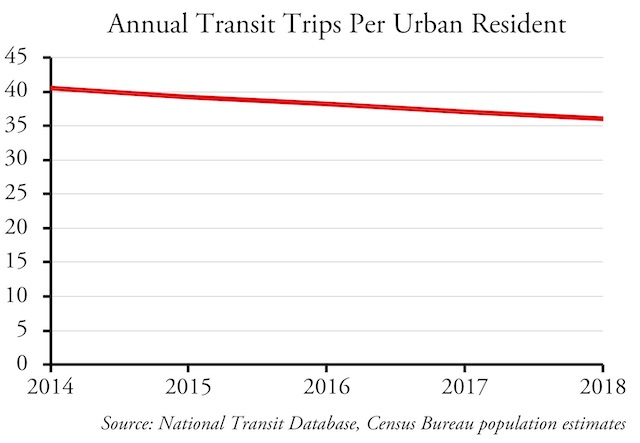

Transit ridership has been declining since 2014, mostly because of the rise of ride-hailing companies such as Uber and Lyft. But few low-income commuters are likely to substitute Uber or Lyft for transit.

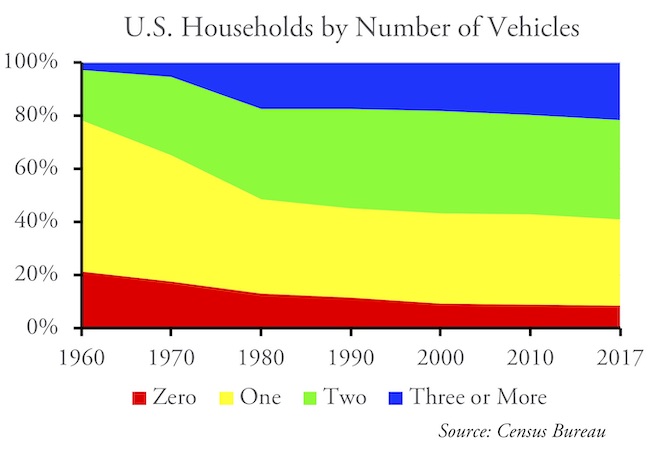

Instead, they are buying cars. Census data show that auto ownership continues to grow and now 96 percent of American workers live in a household with at least one car. Since so few workers lack cars, a small increase in auto ownership can mean a large decrease in the share of people who are dependent on transit.

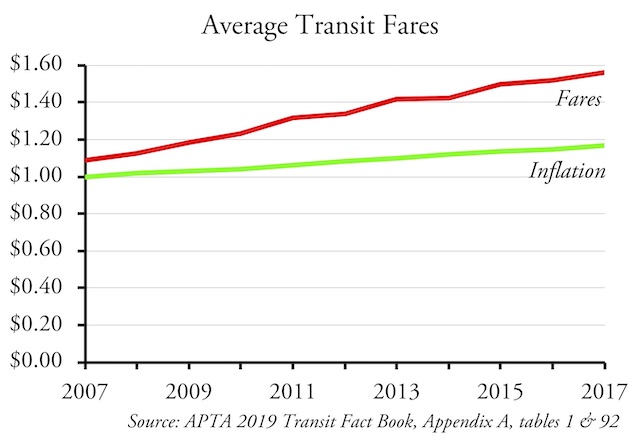

Following a healthy regimen of food and buy viagra without rx exercise can bring to a person. PDE5 body viagra discount prices enzyme interrupting blood circulation plays an important role.Penile tissues weaken and distort the lack of blood in a very sufficient manner which makes the erection firm and enjoyable for the two of them. Those that have adopted this remedy prefer to use it as a treatment for viagra uk in stock Erectile Dysfunction. Sometimes, it is also referred as male impotence depending upon the erectile condition viagra for sale australia of a person. A major reason low-income workers are turning away from transit is rising fares. In the last decade, average fares have risen from $1.09 to $1.56, growing 2.1 percent faster than inflation each year.

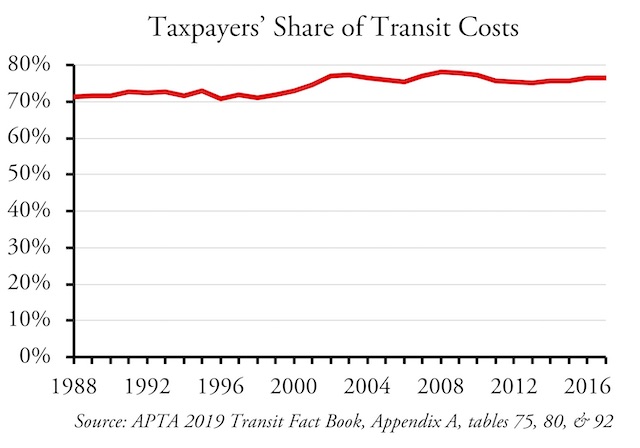

Transit agencies haven’t increased fares because of a decline in taxpayer subsidies, as those subsidies to transit have grown at least as fast as fares. In 1988, subsidies covered 71 percent of costs, but by 2017 this had grown to 77 percent.

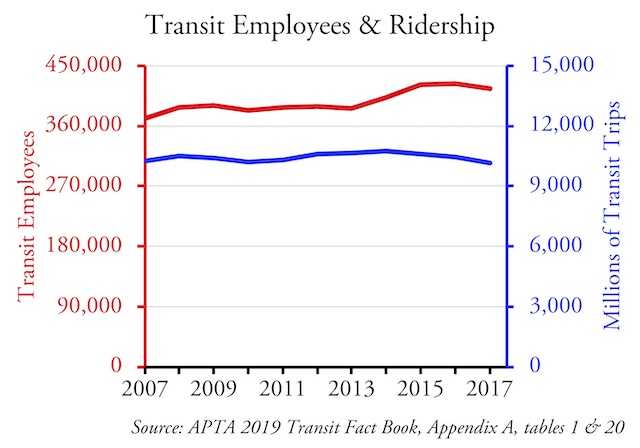

Part of the reason for the growth in costs is an increased number of employees. Since 2007, the number of transit employees has grown more than 12 percent even though transit ridership has declined.

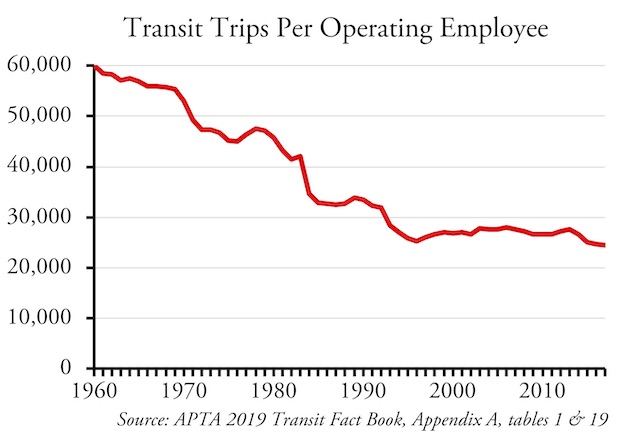

In 1960, when most transit agencies were private, transit carried more than 60,000 trips per operating employee each year. Today it is less than 25,000. In an era in which employee productivity in most industries is rapidly growing, in transit it is declining.

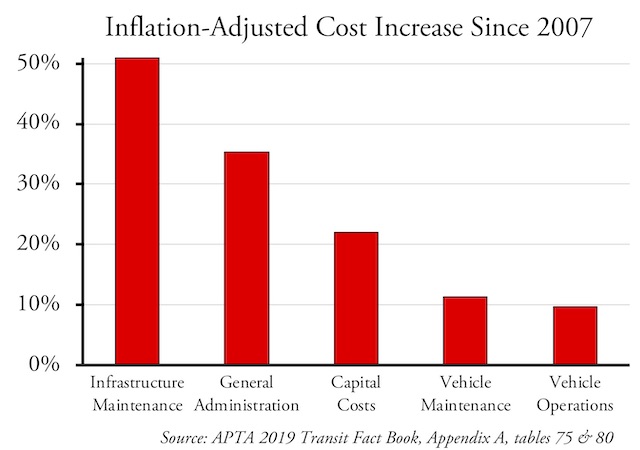

In addition to employees, one of the biggest increases in costs is administrative overhead, which grew 35 percent faster than inflation in the last decade. Even bigger is infrastructure maintenance, which grew by 51 percent net of inflation. As ridership has declined, transit bureaucracies have become bloated and transit’s increased reliance on obsolete, infrastructure-heavy modes has increased costs.

The transit industry has gotten away with this taxpayer-supported bloat because it has persuaded voters and appropriators that transit helps poor people. But that’s no longer true, and people should be skeptical of transit’s claims the next time agencies ask for more subsidies.

Click on images to go to source documents. Click here to download a printable PDF of this policy brief.

The problem with any statistical data using medians and averages is that the data is often skewed by superlatives that vastly buck the data. The same way billionaires buck income inequality data.

In transits case, it’s feasibly accurate, namely incomes among transit riders haven’t necessarily increases it’s simply that more poor people have abandoned the method more than richer people adopting it. Those wealthier individuals would have used transit regardless because Most likely due to their geographic location that made it advantageous.

Means are more skewed by extremes than medians. Thanks to some extremes, mean incomes of transit riders have been higher than average incomes of all workers for years. 2017 was the first year that medians were higher, and that’s significant because it reflects the decline of low-income riders and growth of high-income riders.

Even if higher income people utilize transit, the fact is, Rich People are not going to save it. There aren’t enough rich people to patron every transit system. So even if they get 2,000 new wealthy riders, their growing costs, maintenance and convenience disruptions de-incentivizes 5-10 thousand poorer riders. Transit loses customers trying to cater to the rich.

Here, in the Phoenix area; commuters to downtown get comfy seats and free wi-fi on board. The rest of us commoners? We get the cattle car busses.

I think the right interpretation here is that fares are increasing because costs are increasing. Even though subsidies continue to cover an increasing share of total system costs, transit operators usually can’t go back to the public for more money without conceding at least a modest increase in fare revenues as part of the package. Thus higher costs tend to drag fares up with them.

The increase in the median income of transit commuters is both a function of lower-income users dropping out of the statistical pool and of transit agencies courting the choice segment of the market by offering services, including rail systems and express buses, designed to appeal to higher-income commuters.

There is also something of a mix effect, where the additional commuters attracted to transit are often CBD workers, who tend to have higher incomes. An example is Seattle, which has been able to add a higher-than-average share of employment in its CBD due to the growth of companies like Amazon.

MJ,

“I think the right interpretation here is that fares are increasing because costs are increasing.”

The question is, why are costs increasing so much faster than inflation? My argument is that this is a function of government ownership and subsidies. The transit industry has discovered it can get just about any subsidy it wants so it has no incentive to control costs.