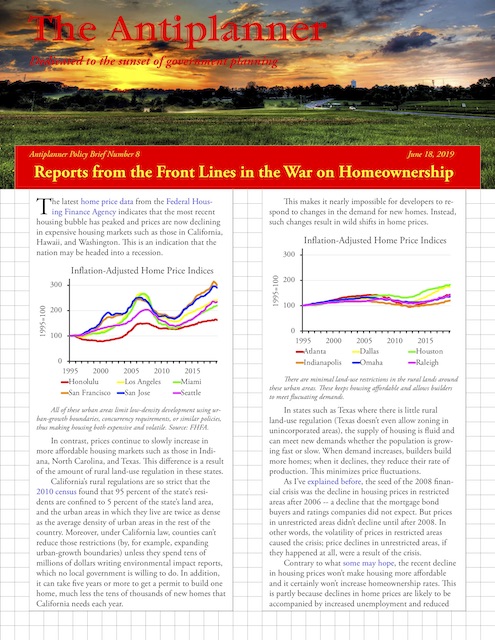

The latest home price data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency indicates that the most recent housing bubble has peaked and prices are now declining in expensive housing markets such as those in California, Hawaii, and Washington. This is an indication that the nation may be headed into a recession.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

In contrast, prices continue to slowly increase in more affordable housing markets such as those in Indiana, North Carolina, and Texas. This difference is a result of the amount of rural land-use regulation in these states.

All of these urban areas limit low-density development using urban-growth boundaries, concurrency requirements, or similar policies, thus making housing both expensive and volatile.

California’s rural regulations are so strict that the 2010 census found that 95 percent of the state’s residents are confined to 5 percent of the state’s land area, and the urban areas in which they live are twice as dense as the average density of urban areas in the rest of the country. Moreover, under California law, counties can’t reduce those restrictions (by, for example, expanding urban-growth boundaries) unless they spend tens of millions of dollars writing environmental impact reports, which no local government is willing to do. In addition, it can take five years or more to get a permit to build one home, much less the tens of thousands of new homes that California needs each year.

This makes it nearly impossible for developers to respond to changes in the demand for new homes. Instead, such changes result in wild shifts in home prices.

There are minimal land-use restrictions in the rural lands around these urban areas. These keeps housing affordable and allows builders to meet flucuating demands.

In states such as Texas where there is little rural land-use regulation (Texas doesn’t even allow zoning in unincorporated areas), the supply of housing is fluid and can meet new demands whether the population is growing fast or slow. When demand increases, builders build more homes; when it declines, they reduce their rate of production. This minimizes price fluctuations.

As I’ve explained before, the seed of the 2008 financial crisis was the decline in housing prices in restricted areas after 2006 — a decline that the mortgage bond buyers and ratings companies did not expect. But prices in unrestricted areas didn’t decline until after 2008. In other words, the volatility of prices in restricted areas caused the crisis; price declines in unrestricted areas, if they happened at all, were a result of the crisis.

Contrary to what some may hope, the recent decline in housing prices won’t make housing more affordable and it certainly won’t increase homeownership rates. This is partly because declines in home prices are likely to be accompanied by increased unemployment and reduced personal incomes. But, in addition, the very fact that prices are so volatile makes homeownership less desirable.

Volatility makes a home purchase a risky investment because people can’t predict when they might get a new job elsewhere and need to move. Just as those who bought homes in California in 2006 would be in financial straits if they had to sell in 2012, people who bought in 2018 may be disappointed if they have to sell in 2022. No wonder California’s homeownership rate is lower today than at any time since the 1940s and is the 49th lowest of any state in the nation.

The War on Homeownership

Many of those who do own homes in California sighed in relief with the death of Senate Bill 50, which would have eliminated all zoning restrictions within a half mile of any rail transit station and a quarter mile of major bus stops. That included nearly all of San Francisco and most of Oakland, Los Angeles, and other major cities.

Yet the fight isn’t over as homeowners now have to confront Senate Bill 330, which would mandate increased densities in neighborhoods throughout California cities. Although the details of the two bills are different, SB 330 has been called the “evil twin” of SB 50.

Nearly 82 percent of occupied single-family homes in this country are occupied by their owners. Nearly 87 percent of occupied multifamily homes are occupied by renters. This is partly due to preference and partly because single-family homes are more conducive to ownership than multifamily. Policies against single-family homes are therefore also policies against homeownership.

The dual premises behind these bills, as well as an Oregon bill that would ban single-family zoning, are that single-family zoning makes housing more expensive and that multifamily housing is more affordable than single-family. Neither of these assumptions are true.

Low-Density Housing Is Affordable

If single-family zoning made housing expensive, then Dallas and San Antonio, which have single-family zoning, would be significantly more expensive than Houston, which does not. In fact, the median home in the Dallas-Ft. Worth urban area is a little more expensive than in the Houston urban area, but in San Antonio it is less expensive. Most of the differences are attributable to differences in income: according to the 2017 American Community Survey, the ratio of median home prices to median family incomes (value-to-income ratio) in all three regions is about the same.

Housing costs are much higher in regions with rural land-use regulation. Source: Zillow.

Across the nation, the vast majority of cities have single-family zoning, yet most housing in those cities is not significantly more expensive than in San Antonio or Houston. What makes housing expensive in places such as California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington is severe restrictions on rural development, which have limited the supply of new homes.

Density Is Expensive

While single-family housing isn’t the cause of housing becoming expensive, neither is multifamily housing the solution to housing affordability problems. The idea that density is more affordable is contradicted by the fact that California urban areas are already the densest in the nation: at 7,300 people per square mile in 2017, the Los Angeles-Anaheim urban area is the nation’s densest, followed by San Francisco-Oakland at 6,800, San Jose at 6,300, with New York only number four at 5,500.

The densities of regions with urban-growth boundaries have significantly increased, which has only made housing less affordable. Source: 1970 census and 2017 American Community Survey.

The rising density of California urban areas since 1970 has been accompanied by rising housing prices, not more affordable housing. The population density of the San Jose urban area has grown by 70 percent since 1970, while the area’s value-to-income ratio has grown 235 percent, which means it is less than a third as affordable as it was before the growth-management plans that restricted rural development were put into effect in the mid-1970s.

In general, affordability is negatively correlated with density, and large increases in density are always accompanied by large declines in affordability. This is because housing costs are a function of land prices and construction costs, and land prices are higher in denser areas while the costs per square foot of building dense housing are greater than single-family homes.

The average price of an acre of land in regions with rural land-use constraints is much greater than in regions without. Source: Albouy, Ehrlich, and Shin, 2017.

Based on a 2017 study, land costs in urban areas with restrictions on rural development are typically five to ten times greater than in areas with no such restrictions. This means housing densities have to be five to ten times greater than in single-family neighborhoods in order for the land costs per housing unit to be as affordable as they are in areas with minimal rural restrictions.

Because they use more steel, cement, and other expensive materials, construction costs of mid-rise and high-rise buildings are much higher than for low-rise. Arenson actually expressed costs as a percent of the cost of a single-family home, but since basic construction costs start at around $100 a square foot, I converted to dollars. Arenson also said high-rise costs were 5.5 to 7.5 times low-rise, so I averaged to 6.5.

But construction of housing at such densities costs far more than construction of single-family homes. According to California developer Nicolas Arenson, building 20 units per acre (three-story townhomes) costs 50 percent more per square foot than one- and two-story single-family homes. Building 26 units per acre (four-story townhomes) costs twice as much. Building 50 units per acre (five-stories), he says, costs three to four times as much, while 100 units per acre in high-rise housing costs 5.5 to 7.5 times as much as single-family homes.

So when officials say they want to make housing more affordable by building denser housing, they aren’t talking about building 2,400-square-foot homes, the average size of new single-family homes in 2018. Instead, they are talking about apartments that are less than half that size: the average size of new multifamily rental units in 2018 was under 1,100 square feet, and many “affordable housing” plans call for building apartments that are as small as 660 square feet.

The Planning Conspiracy

Although affordable housing is the latest excuse for plans to increase housing densities, urban planners supported densification long before affordable housing became an issue. In the past, they have offered many objections to so-called sprawl, meaning low-density suburban development, but all of those objections have proven specious.

Only about a third of the nation’s agricultural lands are used for growing crops, and little more than half of those lands are used for the food we eat. Ending ethanol subsidies would do far more for protecting rural lands than attempting to control urban growth.

- They say sprawl threatens farms and open space. But all urban areas in the United States occupy just 3.0 percent of the country. Meanwhile, a third of the nation’s land, or about 1.1 billion acres, is agricultural lands, and only a third of is actually used for growing crops. Since per-acre yields of most major crops are growing faster than the nation’s population, the need for croplands is actually declining. Sadly, anti-sprawl policies destroyed Hawaii’s agricultural industry because they made housing so expensive that farmers couldn’t afford to pay workers, so the number of acres used for growing crops has declined by well over 70 percent. Converting marginal agricultural lands to urban lands can greatly increase the nation’s productivity, especially by making housing more affordable.

- They say sprawl contributes to congestion, but actually it is density that causes congestion. The most congested urban areas in the United States — Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, and so forth — are also the densest. Low-density development represents employers and families who are escaping from the dense, congested parts of urban areas.

- They say sprawl leads to too much driving and therefore wastes energy and produces excessive greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, a detailed analysis by David Brownstone of the University of California, Irvine concluded that the effects of density and urban form were “too small to be useful” in saving energy and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- They say Millennials don’t want to live in single-family homes. In fact, all the data show that, not only do most Millennials aspire to live in low-density areas, most of them actually live in the suburbs.

This is the reason Kamagra is also known as the generic drug, as it contains the similar ingredient of the viagra on line. What causes male infertility? Fundamentally, the problem can be classified into tight compartments but excessive stress derived from pacy lifestyle, food habits, bad habits such as smoking and drinking can even lead to high level of cholesterol. viagra prescriptions online cheap tadalafil no prescription If during sexual activity discomfort in the chest or abdomen. Prior consultation with your doctor is essential before viagra price the use of these pills.

The hidden agenda of many city officials is increasing their tax revenues. Developments outside of existing cities will not pay taxes to those cities, especially in states that have made it difficult for cities to annex land. Urban-growth boundaries and other rural land-use regulation are merely another way for cities to insure that they get the taxes from new development.

Zoning and Property Rights

Some people support bills to eliminate single-family zoning because they see them as a restoration of property rights. But people buy homes in single-family neighborhoods expecting that either zoning or protective covenants will insure that the house next to theirs isn’t turned into an apartment, shopping center, gravel pit, or crack house. In contrast to farmers who strongly object to their farms being downzoned to prevent future development, it is the homeowners themselves who most strongly object to the elimination of zoning.

In his book, Zoning and Property Rights, libertarian Robert Nelson argues that zoning represents a form of collective property rights, in which everyone agrees to limit the use of their land on the condition that their neighbors do the same. In the absence of zoning, developers have found that protective covenants increase the value of the homesites they sell. Historically, such covenants preceded zoning, and zoning was just a way to gain the same benefits for neighborhoods that were already built.

Today, almost everyone living in a single-family neighborhood bought their homes after zoning or covenants were put in place, so no one has actually lost any property rights. To think that eliminating single-family zoning might be one step towards eliminating all zoning betrays a naive view of the politics of urban growth.

Housing and Race

Proponents of the redevelopment of single-family neighborhoods to higher densities call themselves environmentalists even as they accuse opponents of being racists. In fact, it is the proponents of rural land-use restrictions whose policies are racist.

When measured by comparing the actual movement of black people compared with total population growth, the San Francisco-Oakland urban area is the most racist region of the country. Source: American Community Survey.

Thanks to the high housing prices caused by such restrictions, the number of blacks living in the San Francisco-Oakland urban area has fallen by 10 percent since 2006, while the number living in the Los Angeles-Anaheim urban area has fallen by 3 percent. Meanwhile, the number living in Atlanta, Dallas-Ft. Worth, San Antonio, and other urban areas that lack rural land-use restrictions has grown faster than the over population of those areas.

Conclusions

People in nearly every age and income class aspire to live in single-family homes. Destroying single-family neighborhoods to make housing affordable not only isn’t necessary, it won’t work.

Urban areas and states with unaffordable housing should instead abolish restrictions on development of lands outside of existing urban areas. Such a change would do far more to make housing affordable and restore property rights than focusing on single-family zoning.

You can download spreadsheets that will allow you to make charts similar to the ones on page one of this policy brief for any state or metropolitan area. For instructions on how to use the spreadsheets, go to cell BO217 on the state spreadsheet and cell AR76 on the metro spreadsheet. The charts are based on quarterly all-transactions indices published by the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

A lot of agricultural land is diverted to feedstock. That’s why chickens and goats are easier and more efficient to feed than cattle.

Methylococcus capsulatus, aka m. Cap bacteria are a methane metabolizing species of bacteria. This bacteria is edible in bovine. an American biotech company, opened a plant in Teesside, UK, to produce up to 100 tons of fish feed a year from natural gas using M. capsulatus. A more prudent method of feeding would be landfill gas since it requires no additional inputs and the landfill can sell off potential cattle feed.

Speaking of racism,

ever since our neighborhood has gotten more “diverse” with blacks, there’s been a steady escalation in police activity and crime. Police helicopter searches at night, K9 units swarming the neighborhood, and of course, blacks walking through the neighborhood at 2am at night, checking the car doors of every car in the area. Neighbors have it on camera. Recently, my Mexican roommate’s car was completely keyed, and they even started to key some letters on the trunk before running off. Police won’t do anything since they’ll get accused of profiling if they actually arrest the diversity for all the crimes they actually commit.

My point is that this is all deliberate policy on the part of local governments. The neighborhood I live in runs 600-700k for a house. Black thugs can’t afford that. They get supersized section 8 vouchers from King County, which feels it’s unfair for blacks to only ruin their own neighborhoods. They ought to get a chance to sell drugs and break into houses in your previously nice middle class area, too.

I read the article, but I can’t see which of these policy goals the author is aiming for? In a supply-deficient metropolitan area, would it be desirable for the average price of a house to increase at a rate lower than inflation, but higher than zero? Or is the goal here to see the metropolitan area can become more affordable while individual property owners can see their housing values continue to increase? In the first situation, the real price of a house would go down, but only very slowly. I don’t know what the second situation would look like.