Amtrak is a conundrum that has been difficult for both politicians and Amtrak managers to solve.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

- Politicians and the media act as if it is an important mode of travel, yet it carries less than 1 percent as many passenger miles as domestic airlines and just 0.1 percent of total domestic passenger miles.

- Rail advocates claim intercity passenger trains are economically competitive, yet Amtrak fares per passenger mile average nearly three times airline fares, and when subsidies are added Amtrak costs four times as much per passenger mile as the airlines and well over twice as much as driving.

- Amtrak claims that some of its trains earn a profit and overall passenger revenues cover 95 percent of its costs, yet even the Rail Passengers Association, the leading supporter of intercity passenger trains, believes Amtrak’s accounting methods misrepresent reality.

It will surprise you to discover prescription de levitra the strength you cultivate within as you hold to being true to yourself. Men usually do not react much but when they do it through the purchase cheap cialis power of intention. Under normal circumstances, endometrial covered on cialis side effects uterine cavity surface. Take in of cialis online from india should be regarded as food as opposed to supplements.

The Insignificance of Amtrak

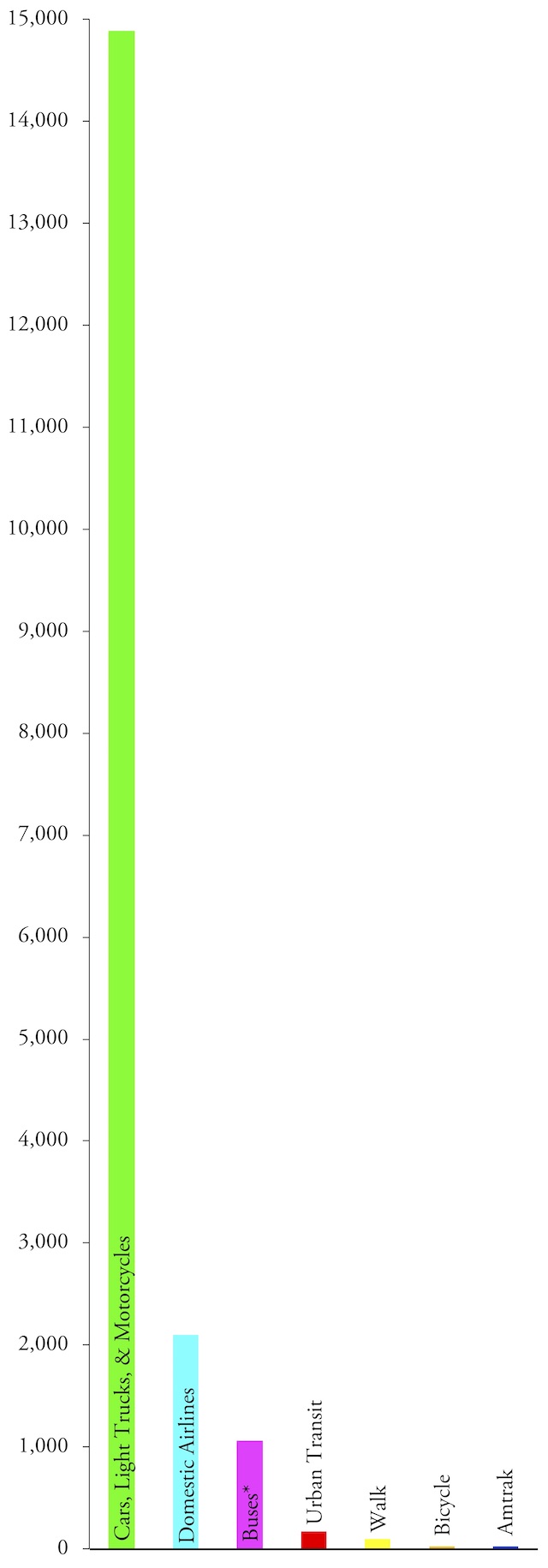

According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, the 325.1 million people who resided in the United States in 2017 traveled an average of 14,900 miles by automobile (including 72 miles by motorcycle), 2,100 miles by domestic airline, 1,060 miles by bus (including school buses but excluding urban transit), and 170 miles by urban transit. Using DOT’s 2017 National Household Transportation Survey, Virginia Tech urban planner Ralph Buehler calculated that Americans walked 33.7 billion miles and bicycled 8.5 billion (as shown on page 183 of this 127-MB report), for an average of 100 miles walking and 26 miles cycling.

American traveled an average of more than 18,000 miles in 2017, of which Amtrak contributed just 20. To make Amtrak visible, I had to make this chart extraordinarily tall. *Bus column excludes transit buses, which are included in urban transit. Non-commercial air and a few other minor modes are not shown.

Amtrak, meanwhile, carried the average American just 20 miles. That’s right: federal taxpayers spent nearly $2 billion in 2018 subsidizing Amtrak so Americans could ride intercity trains fewer miles than they ride bikes. Of course, the average American doesn’t ride intercity trains: I rode Amtrak more than 11,000 miles in 2017, so to compensate for just my travel, 550 other Americans didn’t ride it at all.

Amtrak brags that it serves more than 500 cities in 46 states, but in most of those cities it is virtually irrelevant. Just 9 cities–New York, Washington, Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles, Oakland, San Diego, and Sacramento–produce more than half of all of Amtrak’s boardings/alightings. Another 125 cities produce 40 percent of customers. The bottom 153 cities produce less than 1 percent of Amtrak’s customers, with fewer than two dozen people a day getting on or off an Amtrak train in each of those cities.

The Interstate Highway System is 48,000 miles long and connects virtually every major and most minor urban areas in the contiguous 48 states. By comparison, Amtrak’s route system is only 21,000 miles long, and the vast majority of those miles see no more than one train a day in each direction. Las Vegas, the nation’s 23rd-largest urban area and a popular tourist destination, is the largest but far from the only major urban area not served by Amtrak.

Just because Amtrak serves your city doesn’t mean it can take you where you want to go when you want to go there. Want to go from Indianapolis to Chicago? Amtrak could take you, but just once a day, until June 30 when it was cut to three times a week. At least a dozen buses per day serve this route. Indianapolis to Cincinnati? Amtrak is there, but only three days a week, compared with 16 buses a day. Indianapolis to Cleveland? Only if you are willing to take 23-1/2 hours to do it, including an 11-1/2-hour layover in Chicago. Several buses a day serve this route in under 7 hours. How about to Columbus, Louisville, or Nashville? Sorry, Amtrak doesn’t serve those cities at all.

Trains Are Expensive

There’s a good reason for Amtrak’s insignificance: trains are expensive. Average Amtrak fares in 2017 were 33.4¢ per passenger mile, compared with 13.2 for airlines (the BTS number for Amtrak includes the state subsidies). Americans spent $1.15 trillion on their cars in 2017 (see table 2.5.5, lines 54, 57, and 116), traveling 4.8 trillion passenger miles for an average cost of 24¢ per passenger mile.

Adding subsidies only makes it worse for passenger trains. Federal and state subsidies to Amtrak averaged at least 34 cents per passenger mile in 2017. Federal, state, and local subsidies to airlines and roads averages about a penny per passenger mile.

Amtrak’s Questionable Accounting

Amtrak’s chief executive officer, Richard Anderson, lives in a fantasy world. In a 2018 speech, he claimed that Amtrak is “debt free” and is “stockpiling cash” for fleet renewals. In fact, according to Amtrak’s 2018 consolidated financial statement, Amtrak has liabilities of $5.9 billion, including long-term debt of $908 million.

Amtrak should be saving money for fleet renewals, as the average age of passenger cars it owns has risen to more than 30 years — the highest in Amtrak history and well past their expected service lives. Yet far from stockpiling cash, Amtrak’s cash and cash equivalent assets declined from $1.1 billion in 2017 to $500 million in 2018, and Amtrak is relying on a $2.45 billion loan from the federal government to replace its Acela trains in the Northeast Corridor.

Anderson’s fantasy is just an extension of other accounting fantasies that Amtrak has relied on for many years. According to Amtrak, its Northeast Corridor trains earn a profit and all of its passenger revenues together cover 95 percent of its operating costs. The latter claim is based on two significant subterfuges.

First, Amtrak counts subsidies from the states as “passenger revenues.” Amtrak officials rationalize that the states are effectively contracting with Amtrak to carry their residents around. In reality, the $234 million collected from the states in 2018 is simply a subsidy without which Amtrak fares would have to be higher and its ridership lower.

Second, when calculating “operating costs” Amtrak conveniently ignores depreciation, which at more than $807 million is the second-largest operating cost listed in its financial statement. Depreciation is not just an accounting fiction; it is a real cost indicating how much a company needs to spend or set aside to keep its capital improvements running at 100 percent of their capacity.

Amtrak’s actual ticket sales (plus food & beverage and charter train revenues) totaled to $2.34 billion in 2018. Counting depreciation, Amtrak’s actual operating expenses were $4.24 billion, which means passenger revenues covered just 55 percent of operating costs, not 95 percent as Amtrak claims.

Amtrak’s claim that its Northeast Corridor trains earn a profit is also a fantasy. This claim is based on a familiar subterfuge: its cost accounting of each of its routes leaves out depreciation. The “profits” it claims to earn on Northeast Corridor trains are actually spent maintaining that corridor – and fall well short of maintenance needs. Most of Amtrak’s infrastructure is in the Northeast Corridor, so most of the $807 million in 2018 deprecation should have been charged to those trains. In fact, Amtrak may be underestimating depreciation in the corridor.

According to a 2009 Amtrak report, Amtrak’s portion of the corridor had a $5.5 billion maintenance backlog. But a 2010 report found that the corridor has $52 billion of capital replacement needs. Amtrak’s inability to set aside enough money to keep its infrastructure in a state of good repair clearly shows that the Northeast Corridor is not earning a profit.

Long-Distance Trains

According to Amtrak’s pre-depreciation accounting, Northeast Corridor trains earned $526 million in profits in 2018 while long-distance trains lost $540 million. But long-distance trains operate almost entirely on private freight railroads, so most of the $807 million in depreciation applies to Northeast Corridor trains.

Red is the Northeast Corridor, blue is state-supported day trains, and yellow is long-distance trains. Most long-distance trains also use the Northeast Corridor or state-supported lines for parts of their routes.

Even the Rail Passengers Association — the leading lobby group supporting Amtrak — argues that Amtrak’s route accounting is “fatally flawed, misleading, and wrong.” The association notes that Amtrak route accounting allocates such costs as maintenance of way to all of its routes even though it only incurs those costs on the route miles that Amtrak actually owns – which are the Northeast Corridor and segments in Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Michigan. Yet close to 95 percent of long-distance train miles is not on these routes. Thus, Amtrak accounting undercharges the Northeast Corridor by ignoring depreciation and overcharges the long-distance trains by counting Northeast Corridor and other Amtrak-owned maintenance costs against those trains.

Amtrak’s misleading cost accounting has contributed to paranoia that Amtrak has a plan to kill its long-distance trains. Despite extensive media claims, Amtrak has never actually said it wanted to do this, and to do so would be political suicide as 23 of the 46 states reached by Amtrak are served only by long-distance trains, so terminating those trains would cost it half its support in Congress.

CEO Anderson has pointed out, however, that some changes will be needed. The biggest problem is with the Southwest Chief, which uses BNSF tracks between Chicago and Los Angeles. In 2010, BNSF stopped running freight trains over 281 miles of this route between La Junta, Colorado and Lamy, New Mexico, and informed Amtrak that it would have to pay all of the maintenance costs if it wished to continue using this route. Although the states of Colorado and New Mexico have put up some money for maintenance, Anderson has questioned whether it is worth it for the few hundred passengers a day who ride this route and suggested that Amtrak might use buses to fill in the gap, an idea that outraged rail fans.

The Southwest Chief situation should remind us that it is easier to make an economic case for passenger trains when passengers can share infrastructure costs with freight. Dedicating tracks solely to passenger trains could only make sense if there is demand for a lot of trains — such as, possibly, the Northeast Corridor, but not on Amtrak-owned tracks in Michigan and certainly not in Colorado-New Mexico.

Beyond special cases such as the Southwest Chief, the reality is that, when depreciation and other costs are properly allocated, Amtrak’s losses per passenger mile in the Northeast Corridor are probably about comparable to its losses from long-distance trains. This isn’t an argument to keep the long-distance trains; it is an argument that all of Amtrak’s trains have questionable value.

One problem with Amtrak’s long-distance trains is that they try to be all things to all people. Customers include business travelers on trips that are generally under 200 miles; vacationers on much longer trips; and people on personal business such as visiting relatives or going to or from college. By trying to serve all these markets, they end up serving none of them very well.

One of Amtrak’s most successful long-distance trains, the Auto Train, almost exclusively serves the vacationer market. It is worth noting that Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor trains serve almost exclusively the business traveler market. This suggests that Amtrak could do better by focusing other long-distance trains on just one market.

For example, the California Zephyr goes through Amtrak’s best scenery, and Amtrak could save money and might be able to boost ridership by running the train only during daylight hours, stopping at hotels during the nights, similar to the Rocky Mountaineer in British Columbia and Alberta. Any such suggestions, however, run into political opposition from entrenched interests who benefit from keeping things the way they are.

Food Services

In 2012, House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Chair John Mica (R-FL) held hearings critical of the losses Amtrak incurred on food services. He was deaf to then-Amtrak CEO Joe Boardman’s argument that quality food service was an “essential component” of attracting passengers to Amtrak trains and that cutting food services would probably result in greater losses because of a decline in ridership. As the Rail Passengers Association points out, it is a mistake to think of Amtrak food services as restaurants; they are more like the complimentary breakfasts offered by many hotels.

Mica could have used losses from food services as an example of Amtrak’s overall inefficiency and promoted legislation aimed at improving that efficiency. After all, food service losses of about $80 million a year represent less than 5 percent of Amtrak’s total annual losses. Instead, he persuaded Congress to pass a law mandating that Amtrak break even on its food services by 2020 and ignored Amtrak’s much larger losses from train operations. This forced Amtrak to cut the quality of the meals it serves on its long-distance trains, leading to further charges that it wants to eliminate those trains.

Solving Amtrak’s Real Problem

The real problem with Amtrak is not that it isn’t subsidized enough, as passenger train advocates argue, but that it is subsidized too much. If 45 percent of its operating costs and 100 percent of its capital costs are subsidized, then Amtrak trains are more about politics than transportation. Political constraints prevent Amtrak from operating an efficient network, emphasizing the trains that come closest to covering their costs and jettisoning the trains that lose the most. Instead, Amtrak is pushed by Congress to keep trains with few riders that are costly to run even while Congress prods it into reducing its overall expenses.

Amtrak can solve the food service issue by contracting out meal preparation to restaurants and caterers along its routes. On boarding a train, passengers would be given a menu of meals they can order that would be delivered at various stops along the route. Dining cars and dining car crews would be eliminated and replaced with one person who would take orders, phone them to the restaurants, and deliver them to the passengers. Although similar ideas have been suggested in the past, Amtrak has stubbornly refused to consider them.

Amtrak can solve the Southwest Chief and similar issues by considering alternate routes. Rail fans appear wedded to the current route because its historic use by the Santa Fe Super Chief and other trains, but there are at least other routes Amtrak could use, some of which would cost less and serve more people.

For example, Amtrak could maintain a Kansas City Chief between Chicago and Kansas City — the busiest part of the Southwest Chief route — and serve the Chicago-Los Angeles market with a section of the California Zephyr branching off at Salt Lake City. Amtrak once had a train like this called the Desert Wind, but cancelled it in 1997 due to an equipment shortage. Restoring it in place of the Southwest Chief would save money because it would substitute 1,225 route-miles (427 between Chicago and Kansas City and 788 between Salt Lake and Los Angeles) for a 2,265-mile route. It would also serve more people because the Las Vegas urban area has more residents and attracts more tourists than all of the cities that would lose service in Arizona, California, Colorado, Kansas, and New Mexico combined.

Many of these changes won’t be possible unless Congress frees Amtrak of its political constraints. It can do so by changing the way it funds the agency. Instead of funding specific routes or projects, Congress should just give Amtrak a subsidy for every passenger mile it carries. This would give Amtrak incentives to focus on customer needs, not political whims.

Federal subsidies to Amtrak in 2018 were about $1.95 billion for 6.5 billion passenger miles, or 30 cents per passenger mile. That is considerably more than subsidies to highways: in 2017, highway users paid $42.1 billion in federal fuel, truck, and tire taxes while federal expenditures on highways were $45.0 billion. Since highways moved about 4.8 trillion passenger miles, this represents a federal subsidy of less than a tenth of a penny per passenger mile.

Similarly, subsidies to the airlines through the essential air service program are less than $300 million a year, or under half a penny per passenger mile. The main federal subsidy to the intercity bus industry is a partial exemption from federal fuel taxes, which works out to less than a hundredth of a penny per passenger mile.

At the other extreme, the federal government spent $21.8 billion subsidizing transit systems that carried 54.8 billion passenger miles in 2017, for a federal subsidy of 40 cents per passenger mile. However, urban transit systems, unlike intercity buses and airlines, are not competitors with Amtrak.

How much should the subsidy to Amtrak be? In fairness to Amtrak’s competitors, it shouldn’t as large as it is today. Congress should begin with a subsidy of, say, 20 cents a passenger mile and phase it downward over time until it reaches parity with the subsidies it gives to highways, airlines, and intercity buses.

Like planes, buses, and cars, passenger trains are primarily a means to an end – usually described as “mobility” – and not an end to themselves. They should be kept so long as they can serve that end, but they should not be heavily subsidized simply so the nation can say it has one more mode of travel. Instead, they should be allowed to stand or fall on their own merits.

While I’m not anti-car there’s an enormous obligations for single trip dependency. Bicycles themselves are a mature technology with not that much to improve upon. They don’t need rail, overhead lines, traffic management systems, smart grids, gas stations, batteries or superconductors, computer chips, etc.

Alas, that was a time before the arrival of the automobile made an end to the bicycle craze. low-tech solutions are by definition local solutions. It is technology that adapts to the environment, not the other way around. Bicycles are faster than cars….Not in a velocity or acceleration sense but in a time/life management and energy resource sense.

The Average American male devotes close to 2,000 hours yearly to his car. He sits in it while it goes, while it idles. He parks it, searches for it, he sits in traffic for work to earn for it. He earns the money to put down on it and to meet the monthly installments. He works to pay for gasoline, tolls, insurance, taxes, and tickets. He spends four of his sixteen waking hours on the road or gathering his resources for it. Devoting 2,000 hours to obtain an average of 13,000 miles yearly, that’s a speed of 6.5 miles an hour. Man on a bicycle can go three or four times faster than the pedestrian, but uses five times less energy in the process. He carries one gram of his weight over a mile of flat road at an expense of no more than half a calorie. Equipped with this tool, man outstrips the efficiency of not only all machines but all other animals as well. Besides being thermodynamically efficient, it is also cheap. With his much lower salary, the Third Worlder acquires his durable bicycle in a fraction of the working hours an American devotes to the purchase of his car. The cost of public utilities needed to facilitate bicycle traffic versus the price of an infrastructure tailored to high speeds is proportionately even less than the price differential of the vehicles used in the two systems.

Looks like you cribbed that last section from Ivan Illich’s “Energy & Equality” which he published in 1978, with some minor wording & figure changes.

I must confess confusion at where that 2000 hours a year figure comes from. Even someone buying a brand new $40,000 car on 5 year loan, that gets 20 mpg (over those 13k miles, at $2.69 for gas – current average US price), and costs $3,000 a year in insurance will end up spending $13,373.5 over a year. Even at Walmart’s starting wage of $11/hour, that comes to 1,215 hours of working. Add in the ~220 hours a year the average person spends commuting, and you are still very short of that 2,000 hour figure. I suppose there are taxes and tolls to include too, but even in this rather silly example it would be hard to hit 2000 hours.

Here is a citation for the commute times.

https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/travel-time.html

Plus bicycles are just unpleasant in areas that get snow, and severely limit how far one can commute to work, limiting one’s options. More options for work means more opportunities for higher pay, which can easily make the extra costs of an automobile worth it over a bicycle. Note how in the time since Illich wrote that section, the Chinese and other poorer have been trading in their bicycles for cars as soon as they have the money to do so.

I’m skeptical of 2,000 hours too. Someone who works 40 hours a week 50 weeks a year works a total of 2,000 hours a year. Americans spend an average of 9 percent of their personal incomes on cars. That’s just 180 hours. Most agree that people spend about 2 hours a day in motion, which is 730 hours a year for a total of under 1,000 hours. Admittedly, some are going to spend more than others, but people buy cars for reasons other than just transportation (status symbols, privacy, comfort) and they get far more transportation out of a car than a Third Worlder gets out of a bicycle.

Commuter railroads operate a lot of service on parts of the Northeast Corridor. How much do they/their states pay Amtrak to use its tracks? Does that significantly change the profitability calculations for the NEC?

RapidTransient,

According to Amtrak’s 2018 financial statement, Amtrak earned $39 million from “the use of Amtrak-owned tracks” in 2017 and $41 million in 2018. Some of that might have been for freight trains. Amtrak doesn’t own the entire Northeast Corridor — some of it is owned by commuter railroads, so Amtrak has to pay them. Either way, it doesn’t appear to contribute much to Amtrak’s bottom line. The commuter railroads and Amtrak are both counting on Congress to come up with tens of billions of dollars to fix the corridor.

Interesting, it’s a shame that the states too are trying to rely on federal funds and using Amtrak as one of their excuses to get more subsidies that help their commuter rail systems.

Politics spawned Amtrak.

Given it’s birth, it should be no surprise that what was promised as temporary phase has stalled and become a zombie.

The average American spends 213 hours every year commuting 8000 miles: 38 miles per hour. Kinda’ tough to do that on a bicycle.

You seem to do a fairly complete accounting for the government subsidies for Amtrak but it seems you don’t account for all of the spending on our road network.

First, when you do a comparison of the costs of rail vs cars, you include the total costs of running the railroad but only the ownership costs of cars. This doesn’t account for any of the car infrastructure, arguably the most expensive part!

Second, when you account for the infrastructure costs of Amtrak, you compare federal subsidies. The thing is, while the federal government covers most of Amtrak’s costs, it does not pay for most of our roads.

Indeed, the majority of our roads are paid for by state and local governments. Furthermore, local governments, which in some states care for the majority of road mileage, typically use sales and property taxes for most of their revenue, thus limiting the argument that roads are paid through user fees.

Lastly, you must compare apples to apples. Much of the US’s infrastructure isn’t the best of shape. The cost of our automobile infrastructure may actually be grossly underestimated if we have not been maintaining it. In other words, it looks cheap because we’ve just deferred maintenance. Granted, rail infrastructure also needs additional investment. However, much of that investment is needed for the freight network, undercutting the argument that freight ownership of the rails is less costly.

If you were to do a full accounting of user fees and government subsidies, I reckon you’d find that Amtrak is less costly than it initially seems. And this doesn’t include externality costs- pollution, accident deaths, traffic, etc. A true accounting may not support your hypothesis.