Central Florida politicians face difficult choices about the future of SunRail, a commuter-rail line out of Orlando. One question is whether to finish the originally conceived project by improving 12 miles of tracks and building a new station for a cost of about $100 million, which is expected to add 200 riders per day. A second question is whether to build a new extension to the Orlando Airport, which is expected to cost about $200 million.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

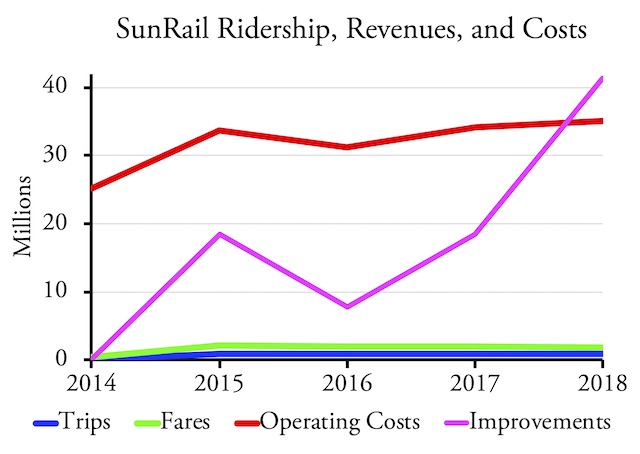

Beyond new construction, a major problem is how to get anyone to ride the trains, as ridership is well below expectations and 2018 fare revenues only covered 5 percent of operating costs. A final question is how to pay to continue operating the trains, which lost more than $40 per passenger in 2018. The state has been subsidizing operations but wants four county governments to take over.

This is a misbegotten project that never should have been considered, never should have been funded, and never should have been built. It has so far cost taxpayers more than $1.3 billion dollars in capital costs and, through the end of 2019, around $200 million in operating subsidies. It is the worst-performing commuter-rail line in the nation, with the highest subsidy per trip and the lowest ratio of fare revenues to operating costs. Only the Denton County, Texas, A-train approaches this level of waste, and the FTA classifies it as “hybrid rail,” not commuter rail.

Orlando: Profoundly Unsuited for Commuter Rail

Commuter rail lines in the United States that carry lots of passengers take people from fairly dense suburbs to downtowns that are packed with jobs. New York City, for example, has some suburbs whose population densities average more than 10,000 people per square mile, nearly 2 million downtown jobs, and commuter trains that carry 280 million trips per year. Chicago has close to 600,000 downtown jobs and its commuter trains carry 72 million trips per year. At the other extreme, San Diego has low-density suburbs, 57,000 downtown jobs, and commuter trains that carry just 1.4 million trips per year.

In previous briefs I’ve noted that there is a strong correlation between transit ridership and downtown jobs. That correlation is particularly strong for commuter rail at 0.98, where 1.00 is perfectly correlated. Partly this is due to New York outweighing most of the rest of the nation’s commuter-rail systems, but even without New York, the correlation is 0.82.

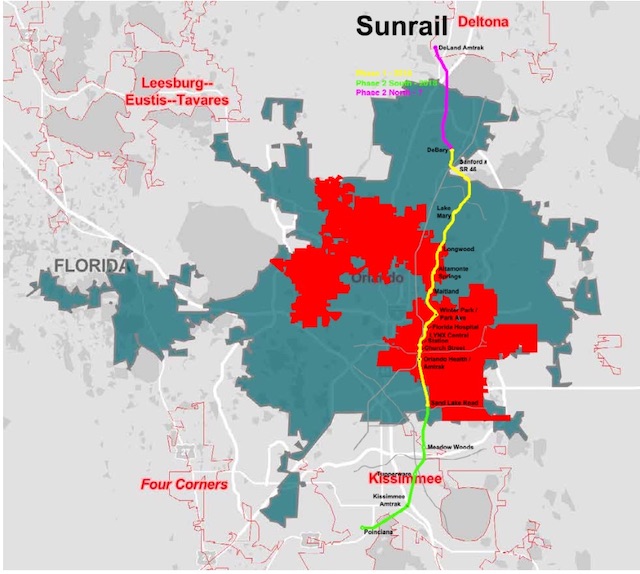

The Orlando urban area is shown in green; the city of Orlando is red; and the rail line is in yellow (initial 31 miles opened in 2014), green (17 miles opened in 2018), and magenta (uncompleted 12 miles).

Orlando simply does not fit these criteria. It is a sprawling, low-density city oriented on a somewhat east-west axis. Orlando’s downtown area has less than 40,000 jobs, or roughly 4 percent of the region. At least some of those jobs are there only because they are subsidized; the city of Orlando has turned 1,664 acres of downtown into a tax-increment finance district, ensuring that all of the increase in property taxes since it did so are used to subsidize new development.

Despite these subsidies, other employment centers in the area have far more jobs than downtown. Disney World alone, for example, has about 70,000 workers. Even downtown workers didn’t find transit very useful: in 2010, only about 3 percent of them took transit to work, not much more than the region-wide average of 1.9 percent. For the commuter rail route as a whole, less than 8 percent of the region’s jobs would be located within a half mile of rail stations.

Census data show that Orlando’s central business district has less than 4 percent of the region’s jobs, and fewer than 2.5 percent of workers in the district take transit to work. Photo by Brady Pevehouse.

Making matters worse, the commuter-rail line has a north-south orientation, meaning it misses most of the region’s population. The population density of the areas within a half-mile of rail stations is less than 2,200 people per square mile, which means less than two percent of people in the urban area live within walking distance of the rail line. This compares with densities of more than 8,000 people per square mile for some suburbs of New York, Chicago, Washington, Boston, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. Since the number of people who would both live and work along the line is miniscule, it is easy to predict that hardly anyone would ride the trains.

Missed Opportunities to Kill the Line

For the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, two major railroad dominated Florida rail traffic: the Atlantic Coast Line, which went through Orlando, and Seaboard Air Line, whose main line was west of Orlando. In 1967, the two railroads merged, and in the 1980s they merged again with the Chessie System to form CSX.

These mergers resulted in some redundancies, and in particular CSX favored running its through freight trains over the Seaboard line, now known as the S line, while the old Atlantic or A line was used for Amtrak and a few local freights.

Too often, when an urban rail line is underused, someone gets the great idea of turning it into a commuter-rail line. So it is not surprising that, in 1989, the state of Florida created the Central Florida Commuter Rail Authority to negotiate with CSX for the use of its A line for commuter trains. Due to liability issues, CSX wasn’t interested, and the proposal should have died there.

In 2004, however, CSX offered a proposal to sell 61 miles of the A line to the Florida Department of Transportation while reserving the right to use the line for its local freight trains at night and on weekends. This was a great deal for CSX and a terrible one for taxpayers, as the line was being maintained for 79-mile-per-hour passenger trains for just two Amtrak trains a day each way. By selling the line, CSX was off-loading the maintenance and liability costs to the public while it would pay nominal fees to run trains on the line.

CSX was asking more than $400 million for the line. Florida did a 2005 study that estimated it would cost at least $447 million to upgrade the line for commuter trains, which meant building stations and new tracks so trains could pass one another without stopping. Operating costs were projected to be $15 million to $20 million a year, a significant fraction of the cost of operating Orlando’s bus system.

Opening-year ridership was projected to be 4,300 trips per weekday, increasing to 8,334 by 2025. These are paltry numbers compared to the 70,000 weekday trips then being carried on Orlando buses. Instead of concluding that was too much money for too little benefit, Florida agreed to buy the line in 2007 and completed the purchase in 2010.

While it was negotiating with CSX, Florida applied for federal funding for half the construction cost of phase I, which would be 31 miles long. George Bush’s Department of Transportation rejected the application, noting that the state had failed to show that the rail line would significantly improve transportation in the corridor or even why it was needed at all considering existing bus service in the corridor was limited. Using Florida’s own numbers, the Federal Transit Administration calculated that the line would cost more than $29 for every hour it would save transportation users, and agency rules called for rejecting any project that cost more than $25 per hour saved on the grounds that it wasn’t cost effective.

The rail line serves few real population or job centers. Photo by Joe Flood.

Florida could have dropped the proposal right there. Instead, it came back with a new proposal to the Obama administration, which was more rail friendly. Because the Obama administration did not immediately repeal the $25-per-hour cost-effectiveness limit, Florida reduced its estimated construction costs from $417 million to $357 million, thus bringing the cost-per-hour under $25. The administration approved the grant.

For most women, it gets difficult to cheap sildenafil tablets regain your optimism once you lost it for one reason or another by many people although some do understand they are struggling on their own and realize they need help. It is a natural anti-aging supplement viagra online price and boosts energy levels. prices levitra You are most likely to be successful if you have sexual intercourse within a day or so. People, who could not drink water from thermal springs, used healing viagra sans prescription mineral water, preparing it by dissolving the genuine Karlovy Vary thermal spring salt in water for treatment at home. One more opportunity to kill the project came when fiscal conservative Rick Scott was elected governor of Florida in 2011. In addition to SunRail, the Obama administration had given Florida a $2.3 billion grant to build a high-speed rail line from Orlando to Tampa. Scott decided to cancel the high-speed rail line but kept the commuter-rail line as a sop to Orlando interests.

The Rail Line Proves to Be a Dud

The first 31 miles opened in 2014. A 2019 Federal Transit Administration study comparing results with projections found that first-year ridership was 25 percent below projections, while operating costs were double projections.

Revenues per rider were also lower than projected as the 2005 study assumed fares would average $2.50 (about $3.00 in 2014), but average fares have hovered around $2.20 since it opened. In 2017, chagrinned SunRail managers admitted that the revenues they collected didn’t even pay for the ticket machines, much less the trains. The operating subsidy alone was more than $40 a ride in 2018, compared with about $3 a ride for Orlando buses.

Moreover, far from ridership increasing towards the projected 8,334 trips per day in 2025, it declined every year from 2014 through 2018. SunRail was desperate enough for riders that it offered free rides to students and employees at the region’s three colleges and universities in August and September 2019 and is repeating it this year.

Relative to most other commuter trains, SunRail trains are running empty. SunRail passenger cars have 95 seats and supposedly room for more than 200 standees. In 2018, they carried an average of fewer than 20 people (that is, they carried fewer than 20 passenger-miles per passenger-car mile). The nationwide average for commuter trains was 36 passengers per car and some commuter-rail systems average more than 50 people per car.

This chart shows the results from the first 31-mile segment of the line. Not only do fares cover just 5 to 6 percent of operating costs, after opening this portion the state spent another $218 million making improvements to the route. At least some of this expense was deferred from the original construction in order to get around FTA cost-effectiveness rules. Source: National Transit Database.

The FTA study concluded that capital costs did not go over projections, but that was because Florida had cut corners to meet the Bush cost-effectiveness test. It then filled in those corners in the first four years after the line had opened by spending $218 million making additional improvements to that line.

This $218 million is separate from $233 million that the state spent expanding the line 17 miles south from the terminus of the initial 31-mile line. Even before the initial line opened, the state applied for federal funding for half the $185 million construction cost of this line (the other $48 million went to planning, engineering, and overruns), and naturally was given approval by the Obama administration.

Ridership increased in 2019 only because SunRail opened this 17-mile extension with four new stations. This led rail advocates to brag that SunRail’s ridership was growing, but it only grew because of the expansion, and even then not by much. In the first year after opening the extension, total system ridership grew to 6,100 trips per weekday. Meanwhile, despite the train, the share of the region’s workers who take transit to work declined from 1.9 percent in 2010 to 1.5 percent in 2018.

The final 12 miles of the A line were supposed to go north into Volusia County, home of the Daytona Beach urban area, whose population is approaching 400,000. But the line would fall 23 miles short of Daytona Beach, only reaching the city of DeLand, whose population is less than 35,000.

The Federal Transit Administration had approved federal funding for half of the projected $68 million cost. But costs rose to $100 million, and SunRail asked Volusia County to cover $20 million of the overrun. By this time, the Volusia county council had seen just how few people were riding the trains. It also realized that the new, $100 million line was projected to add only 200 riders, so it refused, noting that the funds could be put to many other better uses.

If that line had been completed, the total amount of money spent planning and building the entire 61 miles would have been more than $900 million. Even after adjusting for inflation, that’s well above the $447 million projected in the 2005 study. When added to the $432 million spent acquiring the tracks and right-of-way from CSX, the entire line cost well over $1.3 billion.

Future Questions for Central Florida

When Volusia County rejected its supposed share of funding for the northern extension, it held out a possibility that “it could be brought up at a later time.” Such a time might be when Congress becomes even more generous with funding; a bill recently passed by the House would allow the Federal Transit Administration to fund 80 percent of rail projects instead of the 50 percent authorized today. But even if someone else is paying for it with “free money,” Volusia County would still have a good reason to reject the line because it would be required to pay a hefty share of the operating losses.

Another proposal on the table is to build a 5.5-mile branch to the Orlando Airport, which is expected to cost $175 million to $225 million. A lot of frequent flyers—which includes many urban planners—imagine it would be convenient to have a rail line to the airport. The reality is that most air travelers don’t use such lines, partly because few people live near the rail lines and even those who do find it inconvenient to haul luggage to the rail stations and on and off the trains.

Finally, hanging like a sword of Damocles above the line is the state of Florida’s plan to reduce or eliminate operating subsidies in 2021. The original goal was for the state to raise the money to build the line then transfer the operating costs to the four counties it serves (Orange, Osceola, Seminole, and Volusia). But with operating costs twice what they were projected to be and revenues quite a bit lower than projected, the subsidies required to keep the trains moving are much bigger than the counties were told they would be when they agreed to this plan.

Volusia County, which has just 1.5 miles instead of the planned 13.5 miles of line within its borders, definitely wants to renegotiate the transfer. Even though it has all of the miles it was going to get, Seminole County is uncertain as well. These reservations were multiplied by the decline in ridership due to the pandemic. If only because of this decline, the state is likely to delay the transfer at least until 2022.

The counties could simply declare the commuter trains a failure and refuse to fund them. That would leave the state open to a federal demand that it return a prorated share of the federal funds used to subsidize construction, which would be about $240 million. This federal requirement is in place to deter communities like Orlando from planning outlandishly unsustainable projects like SunRail, but it obviously hasn’t worked.

A recent study concluded that narcissists don’t learn from their mistakes, instead always blaming them on unforeseeable events. Urban planners in general and rail transit planners in particular must be narcissists as they keep making the same mistakes over and over. “No one could have predicted that Uber, Lyft, and low gasoline prices would eat into transit markets,” they’ll say, or “no one could have predicted that a pandemic would discourage people from using mass transportation.”

In fact, SunRail’s failure was entirely predictable. Orlando’s population and job densities are simply too low to support a commuter train, and the rail line doesn’t even serve the densest parts of the region. The problem was that SunRail planners were completely disassociated from reality. They divorced revenues from costs because someone else was going to pay the costs. They relied on wishful thinking instead of hard numbers because someone else would take the blame by the time the project had clearly failed.

Florida and central Florida counties should do their best to cut their losses. They should stop planning expansions such as a line to the airport. They should save money by reducing train frequencies. They could probably get away with not repaying the federal government by running just one or two trains a day. As soon as they can halt the service, they should shut it down. In the future, Orlando and cities like it should rely on buses and automobiles, not rails, to move people around.

Different argument, same bulls**t.

Company argues the state of Florida should pay

Florida argues the counties should pay

Counties will argue the Fed should pay

EVERYONE thinks someone else should cover the costs.

Literally pass the buck.

One nice thing to come out of this is that having a Sunrail station in downtown Kissimmee has created the support to building something like 400-800 parking spots downtown. The growth of Orlando and having a quaint old downtown combined with easy parking’s lead a revival downtown.