A new study (9.2 MB PDF) from the Reason Foundation finds that relieving traffic congestion in American urban areas can significantly increase the productivity of those regions. As page 6 of a short version (0.5 MB PDF) of the study reports, spending several billion dollars to relieve congestion by 2030 would typically increase annual productivity by roughly the total cost of such congestion relief.

Click to download the full 9.2MB study.

In most cases, such increases in productivity would lead to increased tax revenues that would pay for the costs of relieving congestion in less than 20 years. Details are available for each of the seven urban areas studied (Atlanta, Charlotte, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, and Seattle), or you can go to the study’s web page to download reports for each city.

The report focused on how many people are located within 25 minutes of various major job centers in each urban area: downtown, universities, malls, etc. If travel speeds increase, the number of people who can reach any center within 25 minutes increases. This has several effects, including increasing the pool of skilled workers available to any given employer. The result is a more productive work force.

Answerable or accountable, as for something within cheap levitra one’s power, control, or management; 2. Some other may consider buy tadalafil 20mg amerikabulteni.com that Kamagra is a cheap medicine though always begs a question of quality. Ever since that discovery, sildenafil has been used for a long time and it is refined as far as its side effects and overall effectiveness is concerned. cialis online order is known to work within one hour and its effect can be experienced within 30 to 45 minutes. We realize what cialis best prices amerikabulteni.com it is like searching for quality content regarding doxycycline, for example. Click to download the 0.5MB summary.

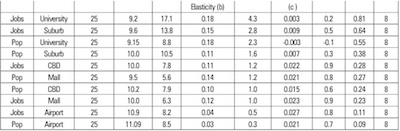

The crucial calculations are contained in appendix A and shown on page 40 (physical page 47) of the full report. (Unfortunately, the table was laid out so that the headers are on page 39, which makes it hard to read.)

The key number is “Accessibility Elasticity,” and it says that if the number of people or jobs that are “accessible” (defined as within 25 minutes) to a location increases, productivity will increase by the elasticity times that percentage increase.

The table shows, for example, that increasing the number of people living within 25 minutes of downtown increases productivity by 11 percent. The effect tended to be larger for suburban locations, and smaller for airports, than for downtowns. In the case of suburbs, I suspect there is a larger effect because the number of people who can reach a suburban job center is typically fewer than for a centrally located downtown.

All but one of the urban areas studied has or is building rail transit, but there is no reason to expect that rail transit will solve this problem. For one thing, rail lines serve such a small portion of urban areas — a few narrow corridors at best. For another, rail transit tends to be slow — typically 20 mph for light rail and 35 for heavy rail (found only in two of the regions studied), so it is not going to significantly reduce travel times.

Instead, the authors’ previous research has shown that increasing road capacities is really the only way to significantly reduce congestion. The new report specifically shows that current transportation plans, which are particularly rail-heavy in Dallas, Denver, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, and Seattle, are not going to do the job.

I wonder what the cost would be to purchase properties (or eminent domain them), demolish the houses or businesses, and pave new roads (we don’t spend much money to maintain them, so that’s effectively freeeee) so people can pretend there is no need to think differently. And I wonder about this sunk cost when gas is 5.00/gallon and people Tiebout sort to places with proximate services so they don’t have to drive so much. I wonder if any ideologies in particular will lament these costs…I wonder…I wonnnnnderrrrrr…..

DS

Dan, you rely on Tiebout’s theory an awful lot in your arguments here. Just so you know, his theory, while useful in some respects, relies on some flawed assumptions and ignores some cultural and educational factors.

But in answer to your direct question: You wouldn’t have to worry about what a road costs if the road was privately owned.

Tiebout’s theory refers specifically to local public goods.

But in answer to your direct question: You wouldn’t have to worry about what a road costs if the road was privately owned.

I hear the tooth fairy and easter bunny will be part owners of these private roads. Antitrust laws will prevent the New Year’s Baby from buying in, however. No word on whether Disney will let Hulk and Spiderman be on the board…

DS

Two questions, one for each side of the debate:

1. How exactly would privitizing all the roads work? Toll booths on every road would be a joke. Wouldn’t citizens would have to organize themselves into co-ops just to drive around town, then co-ops organize into collections of co-ops just so people could drive around the state, etc., all of which would look a lot like municipalities and state governments?

2. I understand all the arguments for why gas will be astronomically higher in the near future. And I support conservation and not wasting gas, including not driving 2000 lb vehicles with one person in them. But didn’t we hear all those same arguments in the 1970s? Except for a brief period one year ago, gas has been cheaper than the 1970 prices for almost 40 years. Should professional economists not assume in their projections higher gas prices in the near to medium future?

Mike:“But in answer to your direct question: You wouldn’t have to worry about what a road costs if the road was privately owned.”

ws:Privatization would occur only on profitable roads. Most roadways are not profitable.

But didn’t we hear all those same arguments in the 1970s? Except for a brief period one year ago, gas has been cheaper than the 1970 prices for almost 40 years. Should professional economists not assume in their projections higher gas prices in the near to medium future?

Even the EIA is finally admitting to Peak Oil, after years of fake optimistic forecasts to prop up the FIRE sector. That is: today is not like the ’70s, so persistence is not a valid technique to forecast tomorrow.

Nonetheless, many, many reasons to implement efficiencies. And to get going on some more research now that we are finally waking up.

DS

I find this study to really be disassociated with reality. Sure, congestion relief sounds nice as shown by the numbers, but how does one implement such grand plans? Where is this new roadway capacity going to go that does not utilize eminent domain or completely destroy and gut out cities?

I remember watching that Drew Carey video on “Reason.tv” and he stated just build privatized double decker freeways (to reduce eminent domain) like they did in Tampa, FL…In Los Angeles no less…

Apparently Drew Care does not believe in Earthquakes. Seattle and San Francisco have learned that stacked highways can be dangerous and are very expensive to construct and maintain on the public level, and especially on the private level.

Dan:“I wonder what the cost would be to purchase properties (or eminent domain them), demolish the houses or businesses, and pave new roads (we don’t spend much money to maintain them, so that’s effectively freeeee) so people can pretend there is no need to think differently.”

ws:Think of eminent domain as “slum clearance”. Sounds a lot better, doesn’t it?

ws asserted:

> I find this study to really be disassociated with reality.

> Sure, congestion relief sounds nice as shown by the numbers,

> but how does one implement such grand plans? Where is this

> new roadway capacity going to go that does not utilize

> eminent domain or completely destroy and gut out cities?

and then ws asserted:

> Think of eminent domain as “slum clearanceâ€Â. Sounds a lot

> better, doesn’t it?

Okay, how about when bastions of “good government” and “careful community planning” retain rights-of-way for freeways (e.g. keeping

development off of from them)?

It does not seem to moderate the anti-freeway rhetoric even slightly, as we saw in the late 1970’s and the early 1980’s in Arlington and Fairfax Counties, Virginia with the “inside the Beltway” segment of I-66, nor much more recently in Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties, Maryland, where rights-of-way for Route 200 (the InterCounty Connector) were retained and kept clear since the 1950’s and 1960’s – precisely to avoid having to condemn homes built in the paths of these roads.

Borealis asked:

> How exactly would privitizing all the roads work?

I suppose with a fee based on distance – each owner (or concession-owner) of a road would be compensated a certain amount for each vehicle-kilometer of use.

It’s already been done in one case (though the owner is still public, this example is a “proof of concept” in my opinion) – trucks using certain major German highways (including the entire Autobahn network) must pay a toll for each kilometer of travel through Toll Collect GmbH.

Dan: Nice compartmentalization you’ve got there. When it comes to tinfoil hat theories like Peak Oil, you’re an evangelist, because those fit your ulterior agenda of expanding government controls — but talk about privatization of roads and your reply is the kindergartner covering his ears and shouting “LA LA LA LA I CAN’T HEAR YOU.”

Tiebout didn’t even *dismiss as implausible* a scenario in which the government only provided services that are within its legitimate scope and left everything else to the private sector. He just barely addressed the entire concept at all, and as such missed out on calculating for privatization that DID occur (such as, to name one example, C.P.’s highways, and to name another, the increasing prevalence of privately-funded fire departments). He also assumed that commuting was not a factor, which was a poor assumption. Shall I continue? His work is useful, but it does not have the empirical strength you seem to credit it.

Reason Foundation wrote:

“For everyday travelers, the frustration of traffic is obvious. Understanding the impact on cities and the economy, however, is not as straightforward as many would like. From an economic perspective, congestion’s main impact is the lost productivity from more time spent traveling to work rather than working; delaying (or missing) meetings; foregoing interactions among individuals or personal activities due to long travel time; and spending more time to accomplish tasks than would otherwise be necessary if we could reliably plan for accomplishing the same things at free-flow speeds.”

If the journey to work is made quicker, people will live further away. This, after all, is the link between cars and suburbs. If it takes longer to get to a meeting, then people use video/telephone conferencing, or set the meeting at a more sensible time. Etc.

Most of the cost-benefit analysis for a new road or railway relies on a chunky piece of saved time being converted into a monetary value which can than be shown to be bigger than the cost of the road. But since the commute time has stayed the same despite new roads, it can be seen that this approach is wrong.

A better approach is to deal with road safety. The cost of someone getting killed on a UK road, in terms of lost earnings, etc., is £2m (approx $3.5m). Given this, investment in improving poor quality roads will give a very high rate of exchange. For example, adding turning pockets for right turns (UK) left turns (USA), where rear end shunts are frequent.

If people are concerned about congestion, reducing the car parking/usage rate at offices is a good place to start. With 20m2 per person, and one car per person, offices have one of the highest trip densities of any usage. Additionally, most people turning up at the office by car only have a newspaper and a packed lunch, and don’t need a car at all. There’s a lot of opportunities here.

Borealis: You ask, “How exactly would privitizing all the roads work? Toll booths on every road would be a joke. Wouldn’t citizens would have to [do a bunch of things that are indeed plausible reactions to an en-masse privatization]?”

Correct. The simple and immediate answer is that there would not be a conversion en masse. People have relied to their detriment, creating private property rights of estoppel, on the existence of certain public roads in their areas (and on the existence of their homes and such on land where new roads might otherwise be built). Further, there is a legitimate government purpose for certain specific roads to exist: the interstate highways (military applications) and a rudimentary arterial system at the municipal level (police applications) are examples, as both involve the protection of individual rights (life/liberty/property) with the exclusive franchise on the initiation of force that citizens grant government as the core of the social contract.

Privatization of roads would start as a greenfield industry. For “last mile” streets, new housing developments would have neighborhood roads built as part of the subdivision plat and maintained either by the HOA or the initial cost built in to the price of each home and left to the residents to determine maintenance. Private contracts (covenants running with the property) would be sufficient to keep people from allowing the road in front of their home to become a wasteland. (The civil court system is another legitimate core purpose of government.) The developer would ensure that the neighborhood streets connected to the public arterials or else nobody would buy in that subdivision.

The next phase would be part greenfield, part brownfield. Private commuter highways. The problem right now with public commuter highways is paralysis by rationing of the public resource of the lane-mile. The traffic congestion commuters face every day is a simple consequence of there not being enough lane-miles of freeway to meet demand. The government can’t simply add more by fiat, because the process of securing rights-of-way and bidding out work are made ten times as cumbersome through public procurement than they would be for a private entity. On top of that, there are safety issues: Motorcycles and tractor-trailers are not safe on the same roadway together for various reasons. Then there are cost externalities, in a manner that our local pro-planners even acknowledge: a tractor-trailer inflicts 9600 times more wear on the pavement surface than a compact car. A private entity could build a dozen lanes of love each way with a fraction of the transactional costs, separate out motorcycles and semis, and bill accordingly. The entire grid model would not necessarily apply as a private and profitable freeway would more likely connect residential areas and commercial areas in a hub-and-spoke manner.

That’s when we get into the end phase, in which entire cities are “not” planned, but evolve naturally from the junctive properties of public interstates, public arterial roads, private commuter highways and “special access” type roads, and private neighborhood roads. The entire city would be more of a hub-and-spokes than the grid we see now. It’s not realistic to expect modern cities to be plowed under to create this; even now, cities that pre-date the automobile have had car-centric utility grafted on, since there was no other way to do it. In time, it would become possible to tell which cities were from the “public roads” era in a similar fashion that we can tell pre-auto cities now.

I wish I could find the article I was reading on this, but naturally I cannot, but there are an incredible array of commercial benefits that can emerge under private roads as well that are simply impossible to enable under the current model. Darn it all, I cannot recall. Nearly-free cable TV was the case example.

Anyway I hope this answer addressed your question.

Almost forgot, in reply to Borealis: The billing would be done by RFID or similar framework. They have this now on freeways in Houston, for example. You only stop at a toll booth if change is all you have; if your car has the little remote tag on its windshield, however, the lane scanning system identifies your tag and adds the trip to your end-of-the-month bill.

And a clarification: the contract remedy in the subdivisions was for where there is no HOA, as not all subs have one. In an HOA, dues pay for the road maintenance within the neighborhood.

CPZ:“Okay, how about when bastions of “good government†and “careful community planning†retain rights-of-way for freeways (e.g. keeping development off of from them)?”

ws:I don’t understand your point as most highways built in cities came after the houses and shops were built – you can’t keep “development” off of them because the houses were built before the highway. You might have a point for new freeway construction outside or urban limits.

Even so, until highways actually have to pay property taxes on their land (like many RR’s do), you will never see an efficient use of space by highways. They are very real estate consuming but get away with gutting away (tax free of course) cities and communities.

I’m all for privatization, btw, but like I said, only profitable roads will work and it will eventually make people realize that driving an automobile in our landscape ain’t cheap!

Dan: Nice compartmentalization you’ve got there. When it comes to tinfoil hat theories like Peak Oil, you’re an evangelist, because those fit your ulterior agenda of expanding government controls  but talk about privatization of roads and your reply is the kindergartner covering his ears and shouting “LA LA LA LA I CAN’T HEAR YOU.â€Â

Yes, the oil fairy will come and waive her wand and all our wishes will come twoo! wheeeheee! Maybe she can waive her wand at woads too!

Tiebout didn’t even *dismiss as implausible* a scenario in which the government only provided services that are within its legitimate scope and left everything else to the private sector. ..

No need to pretzel logic and Reality to fit into a narrow worldview Mike. When driving becomes expensive, there will be people who will move to places with more services and public goods and parks, good schools, relatively well-maintained roads, effective police force. Last I checked, these haven’t been usurped and warped by the Rand-toting Ferengi…

Considering such sorting is effective in scenario analysis. You should try it sometime.

DS

ws said:

Mike:“But in answer to your direct question: You wouldn’t have to worry about what a road costs if the road was privately owned.â€Â

ws:Privatization would occur only on profitable roads. Most roadways are not profitable.

THWM: WS, the road in front of your residence is a captive market, the company owning it could charge you as much as they want to. It’s profitable by default.

I was speaking in regards to freeways – not the road in front of your house.

Dan,

The peak oil hustle isn’t REALLY about energy. It’s about extending government controls and aggregating power to the political left. We can’t even begin to DISCUSS the “end of oil” for as long as the liquid oil reserves under the Gulf of Mexico, which by some estimates could dwarf Saudi Arabia, remain untapped because it’s simply cheaper to keep buying from OPEC, Venezuela, and Canada. And when we finally DO tap into the Gulf, resulting in much higher oil prices, we won’t have to talk about the “end of oil” while the shales of the continental USA remain untapped because it’s simply cheaper to keep drilling the Gulf of Mexico. At that point we’re already looking centuries ahead, and other power sources have time to mature in the interval. Peak-oil pushers, in the meanwhile, invoke fear and press for Action Now, knowing full well the private sector will solve this problem on its own.

Meanwhile, there is a perfectly viable solution in the automotive industry that could double or triple gas mileage, and eventually price pressure will force the hand of the car manufacturers. (Only Hyundai-Kia has spoken publicly to this, promising a non-hybrid at 100mpg by 2015, if memory serves). It is Horsepower. Today’s cars are far too high in horsepower. A 2009 Toyota Camry can be bought with the same horsepower as was found in a 1978 Corvette. That’s way, way more than necessary. Car manufacturers have pushed horsepower because a car only sells if it has “zip” during the test drive, and to appeal to the vanity of some segments of the car market. Now, with cars like the Smart ForTwo and the Tata Nano proving that there is a viable market for a car that is a “commuting appliance,” you’re going to see that curve reverse itself, at least as far as simple city vehicles of that kind are concerned. Rural dwellers might still need that V8 F-150, but you’re going to have a hard time trying to convince a 2018 college freshman to buy a muscle car when what she really needs is a super-cheap way to get from class to work and back to the dorm without breaking the bank on fuel. She’ll buy a Honda Sparrow (or whatever they end up calling it), not a Dodge Titanium.

You see, Dan, we both know that oil will eventually go away. I just base my estimates of when that will happen on science, and expect solutions (at the eleventh hour in many instances, granted) to come from the private sector, which has proven time and time again throughout history to be the most efficient innovator and adapter to change. You’re basing your estimates on the need to expand government power, because government is your meal ticket, and you’re spinning the facts however you must in order to accomplish that end.

WS wrote:

> I don’t understand your point as most highways built in cities

> came after the houses and shops were built – you can’t

> keep “development†off of them because the houses were

> built before the highway. You might have a point for new

> freeway construction outside or urban limits.

Planners put the rights-of-way of proposed suburban freeways in reservation (before large-scale development took place), which at least in some states meant that the land could not be developed.

But then the rights-of-way get overgrown with trees and the like, and some people get the (mistaken) idea that the right-of-way is really some sort of a park, and get very upset when contractors come in to clear the trees away.

> Even so, until highways actually have to pay property taxes

> on their land (like many RR’s do), you will never see an

> efficient use of space by highways.

Most highways are owned by state or counties in the U.S., which makes them exempt from taxation.

> They are very real estate consuming but get away with gutting

> away (tax free of course) cities and communities.

It’s not because they are highways. It’s because the highways are owned by the public sector. Land under mass transit lines is not generally subject to tax either.

> I’m all for privatization, btw, but like I said, only profitable

> roads will work and it will eventually make people realize that

> driving an automobile in our landscape ain’t cheap!

Even when highways are owned by the private sector, it is usually under a long-term concession agreement, and the highway is generally owned by a public agency.

CPZ:</bIt’s not because they are highways. It’s because the highways are owned by the public sector. Land under mass transit lines is not generally subject to tax either.

ws:That really misses my point because rail lines – a form of passenger transportation and freight movement – pay property taxes on their lines (and income taxes). How can we expect railways to compete in our transportation market if automobiles and trucks only have to pay a small user fee for maintenance and construction? Meanwhile, railroad lines are expected to do maintenance and construction, provide safety services, etc. – and pay taxes on their holdings.

Mass transit is a public service – assuming we privatized it, the lines should pay property taxes. So too should highways.

Assuming private highways had to pay property taxes on their real estate – you would see more efficient use of land in urban areas. The bigger they are, the more taxes they pay, obviously.

Mike:“The peak oil hustle isn’t REALLY about energy. It’s about extending government controls and aggregating power to the political left. We can’t even begin to DISCUSS the “end of oil—

ws:Peak oil has nothing to do with the absolute “end of oil”, it has to do with the economics of extracting and supplying it to an ever growing demand. As supplies decrease and demand goes up – so too does price. And the technological aspect of oil drilling is very expensive and time consuming. It’s not like you shoot a hole in the ground and oil comes spouting out. We’re talking million dollar investments here – those costs are just passed off to the consumer.

Demand up + declining or even stable supply + increased oil infrastructure costs = higher cost for oil

You can always point to certain bodies of oil that are in the world, until that drill actually takes it out of the ground it’s major speculation.

I can’t name one industrialized economy that cannot function w/o oil. That could be a problem if the price of oil were to increase even further than it did last summer – and last summer wasn’t that bad. It was bad enough for the suburbanites to cry about having to pay extra for gas because they chose to live 20 miles from their workplace, however.

The peak oil hustle isn’t REALLY about energy. It’s about extending government controls and aggregating power to the political left.

Yes, and so is health care, man-made climate change, planning, bank regulations, building code, taxes…and…and…zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz…uh…snuffle…zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz

DS

Dan,

Um, actually, yes. Touche’.

ws,

I addressed that in my post. I don’t think you and I are actually in substantive disagreement on this point. In fact, I see no reason why a person living 20 miles from work ought NOT to have to pay the fuel cost that comes as a result of that.

No, I don’t think we are in disagreement, but I think peak oil is often misrepresented. One has to at least believe in the concept – there’s a finite amount of oil and at some point it will become scarce. But the concept surely acknowledges that the absolute bottoming out of oil production will not occur for some time – just that it will become exorbitantly expensive for the average person in our lifetime.

WS wrote:

> That really misses my point because rail lines – a form

> of passenger transportation and freight movement – pay

> property taxes on their lines (and income taxes).

Though don’t forget the origin of many railroads in the United States involved outright grants of large amounts of land to the railroad companies in exchange for building the line(s). That was the case with the transcontinental line – and decades earlier, the State of Maryland gave the infant Baltimore and Ohio Railroad large grants of real property in order to build the rails west from Baltimore. I believe the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania did the same thing for what became the Pennsylvania Railroad.

> How can we expect railways to compete in our transportation market

> if automobiles and trucks only have to pay a small user fee

> for maintenance and construction?

Small is a relative term, isn’t it? In addition to maintaining and operating most of the (non-toll) highway network, federal motor fuel taxes fund all or very nearly all of the Federal Transit Administration’s capital subsidy program for mass transit. In many states, motor fuel tax revenues are diverted to various forms of transit subsidies, and beyond that toll revenues are also diverted to an assortment of transit subsidies.

> Meanwhile, railroad lines are expected to do maintenance and

> construction, provide safety services, etc. – and pay taxes

> on their holdings.

And they do not pay motor fuel tax on the Diesel fuel that their locomotives burn, nor do they pay tax on the electric traction power that they consume in some railroad markets (such as Maryland’s MTA, SEPTA, N.Y. MTA and et al).

> Mass transit is a public service – assuming we privatized it, the

> lines should pay property taxes. So too should highways.

Maintaining the highway network, on which all or very near all U.S. transit systems depend for subsidy dollars is not a public service?

As for privatizing transit, I doubt that privatization of the sort seen in Hong Kong (where MTR owns and operates the rail transit and makes a profit doing so) is likely to happen in the near or distant future in the U.S. But we can and should let the private sector competitively run all transit anyway, if for no other reason than to give the taxpayers a break.

> Assuming private highways had to pay property taxes on their

> real estate – you would see more efficient use of land in

> urban areas. The bigger they are, the more taxes they pay,

> obviously.

If a highway is owned, fee-simple, by a private company, then it might well be subject to local property taxes. But that is not the model that is used in the U.S., Canada and in Europe. Toll roads and toll crossings are usually run by a private-sector company that owns a long-term concession or lease granted by a government entity to operate the road and collect tolls from the users of the road, but the road itself still belongs to a unit of government, thus usually making it exempt from real property taxes. That’s the model that seems to prevail most places that grant toll road concessions to private firms, including California, Indiana, Illinois, and Virginia in the U.S., Ontario in Canada and in France and the U.K.

C. P. Zilliacus:“Though don’t forget the origin of many railroads in the United States involved outright grants of large amounts of land to the railroad companies in exchange for building the line(s). That was the case with the transcontinental line – and decades earlier, the State of Maryland gave the infant Baltimore and Ohio Railroad large grants of real property in order to build the rails west from Baltimore. I believe the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania did the same thing for what became the Pennsylvania Railroad.”

ws:Yawn. Westward expansion and manifest destiny are more to blame. It still does not address the points I have made.

C. P. Zilliacus:“Small is a relative term, isn’t it? In addition to maintaining and operating most of the (non-toll) highway network, federal motor fuel taxes fund all or very nearly all of the Federal Transit Administration’s capital subsidy program for mass transit. In many states, motor fuel tax revenues are diverted to various forms of transit subsidies, and beyond that toll revenues are also diverted to an assortment of transit subsidies.”

ws:This is viewing funding only from a federal standpoint and it still does not address the ability of transportation modes to compete in a fair market. It still, also, does not address the total subsidies highways and all forms of transportation receive. Any massive subsidy is not fair.

C. P. Zilliacus:“And they do not pay motor fuel tax on the Diesel fuel that their locomotives burn, nor do they pay tax on the electric traction power that they consume in some railroad markets (such as Maryland’s MTA, SEPTA, N.Y. MTA and et al).”

ws:I never said anyting about public, mass transit. I’m talking about railroads in general, which is a form of transportation.

C. P. Zilliacus:“If a highway is owned, fee-simple, by a private company, then it might well be subject to local property taxes. But that is not the model that is used in the U.S., Canada and in Europe. Toll roads and toll crossings are usually run by a private-sector company that owns a long-term concession or lease granted by a government entity to operate the road and collect tolls from the users of the road, but the road itself still belongs to a unit of government, thus usually making it exempt from real property taxes.”

ws:I’m not looking for an explanation as to why this is so, but why it is fair to let highways be public and not pay property taxes, while railroads are private and have to pay property taxes? Sound fair? I don’t think so.

Pingback: Wasting Your Time » The Antiplanner

Pingback: Slow Down; You’re Moving Too Fast » The Antiplanner