From the Department of Bad Ideas for Transportation (DOBIT) comes a new one: transit parity, which means the federal government should spend as much money on transit as it spends on highways. This compares to the current system where about three times as many federal dollars are spent on highways as on transit. While transit parity is right up there with free transit when measured on the idiocy scale, at least 33 members of Congress have signed onto a transit parity resolution.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Since this issue is likely to be raised in a Biden-led Democratic Congress, here are ten reasons why it is a bad idea. Some of these reasons are obvious, but this policy brief will provide details most people might not have. Other reasons have been mentioned in past policy briefs, yet they are worth repeating just to counter the nonsense that is so often repeated by transit advocates.

- One Percent of Passenger-Miles

According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, transit carried almost 54 billion passenger-miles in 2018. That sounds like a lot, but highways carried more than 5.4 trillion passenger-miles, or 100 times as many. (It’s 103 times, but BTS’s bus numbers are questionable so I rounded down to 100.) Even in urban areas, transit carries no more than 1.6 percent of passenger travel. Why should half of all federal surface transportation dollars go to a form of transportation that carries only 1 percent of personal travel?

- Zero Percent of Freight

The Bureau of Transportation Statistics also says that highways carried more than 2 trillion ton-miles of freight in 2018. How much did transit carry? Zero. The pandemic has taught Americans just how important the supply chain of consumer goods is to our day-to-day lives. Apparently, transit-parity advocates have already forgotten that lesson.

- Most Funds Are from Highway Users

Advocates of transit parity concede that most federal highway and transit dollars used to come from gas taxes and other highway user fees. Yet they point out that Congress has added $144 billion in general funds to the Highway Trust Fund since 2008. Even with that infusion, however, most money still comes from highway users.

In 2018, for example, highway users paid $44 billion into the Highway Trust Fund. Spread over the thirteen years between 2008 and 2020, $144 billion is $11 billion a year. Thus, 80 percent of the Highway Trust Fund still comes from highway users.

Transit received 15 percent of the $44 billion collected from highway users in 2018. Meanwhile, according to table FE-210 of Highway Statistics, almost 30 percent of the $144 billion in general funds given to the Highway Trust Fund went to transit. In addition, transit received at least $3.5 billion federal dollars that didn’t come out of the Highway Trust Fund. Overall, transit is already getting almost half of the general funds going to highways and transit in addition to the nearly 20 percent it gets from highway user fees.

- Highways Users Lost $201 Billion

Congress may have added $144 billion to the Highway Trust Fund since 2008, but table FE-210 reports that only about $105 billion of that went to highways. (Table FE-210 hasn’t yet been published for 2019 so I’m estimating for that year.) This doesn’t come close to covering all of the highway user fees that Congress has diverted to subsidize transit since 1983.

When Congress created the Interstate Highway System in 1956, it dedicated all excise taxes on motor vehicle fuels, highway vehicles, and tires exclusively to the Highway Trust Fund, which was exclusively used for highways. In 1982, when Congress raised the gasoline tax from 4 cents to 9 cents per gallon, it broke the “trust” in the trust fund by specifying that one penny of the increase would go to transit.

Since then, Congress has increased the gasoline tax to 18.3 cents and dedicated 20 percent of all increases to transit so that transit now gets of 2.86 cents per gallon or about 16 percent. In addition, in 1991 Congress made some of the highway’s share of funds “flexible,” meaning states could choose to use them on either transit or highways.

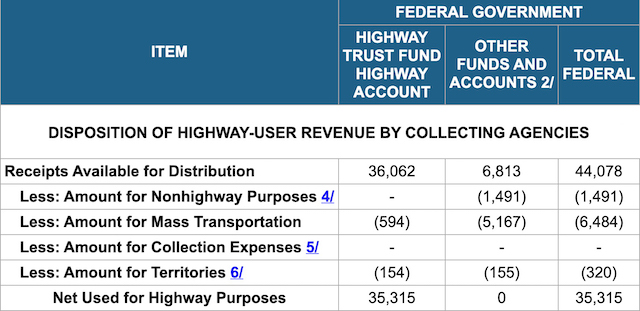

The amount of money that has gone from highway users to transit can be tracked in table HF-10 of the Federal Highway Administration’s Highway Statistics series. A portion of the 2018 table is shown below.

Under “Other Funds and Accounts,” the table shows $5,167 million going to “Amount for Mass Transportation.” That’s the 2.86 cents in gas taxes dedicated to transit. This amount started appearing in the 1983 Highway Statistics. Under “Highway Trust Fund Highway Account,” the table shows $594 million going to mass transportation. That’s the share of flexible funds that states decided to spend on transit. This amount started appearing in 1993. Thus, transit received almost $6.5 billion of the $44 billion collected in highway user fees in 2018.

The table HF-10s since 1983 reveal that a total of $154.3 billion in highway user fees were spent on transit, with $131 billion coming from the pennies per gallon dedicated to transit and $23 billion from flexible funds. When adjusted for inflation using GDP deflators, that adds up to more than $201 billion through 2019.

By comparison, when the $105 billion of highway’s share of general funds added to the trust fund since 2008 is adjusted for inflation, it adds up to about $110 billion (including likely estimates for 2019 and 2020). In short, diversions of highway user fees to transit have been roughly double the general funds spent on highways.

- Transit is Dying; Driving Is Growing

Between 2014 and 2019, driving grew at 1.5 percent per year, compared with population growth of 0.6 percent per year. This means per capita driving increased by almost 1 percent per year from 9,506 miles in 2014 to 9,959 miles in 2019. Over the same time period, transit passenger-miles dropped by more than 5 percent and per capita passenger-miles fell 8 percent from 180 to 165 miles per year.

More than just a short-term trend, this is a continuation of trends that go back a century. Transit trips per capita (counting all Americans, not just urban Americans as I sometimes do) reached 156 in 1923, then declined until gas rationing during the war pushed it up to 175 in 1945. Since then, it has fallen to just 30. Meanwhile, driving has grown from 624 miles per capita in 1920 to almost 10,000 miles in 2019.

- Transportation Should Pay for Itself

“Public transit is a public good,” one of the advocates of transit parity erroneously claims. In fact, unlike national defense or public health during a pandemic, transit is not a public good in the economic sense that it benefits everyone whether they pay for it or not. Instead, the primary beneficiaries of transit and other transportation are the transportation users, and they should be the ones to pay the costs.

Of course, there are side-benefits to mobility just as there are side-benefits to keeping people sheltered and fed and just about everything else. But subsidies don’t ensure that the ones who receive the side-benefits are actually the ones who are paying the costs.

More important, agreeing to subsidize things because they may generate side-benefits invites bureaucrats and special-interest groups to fabricate claims of side-benefits in order to increase their subsidies. This has already happened with transit, whose advocates make outlandish claims about how it is green, promotes social justice, and gives people access to economic opportunities when (as will be shown below) it does none of these things.

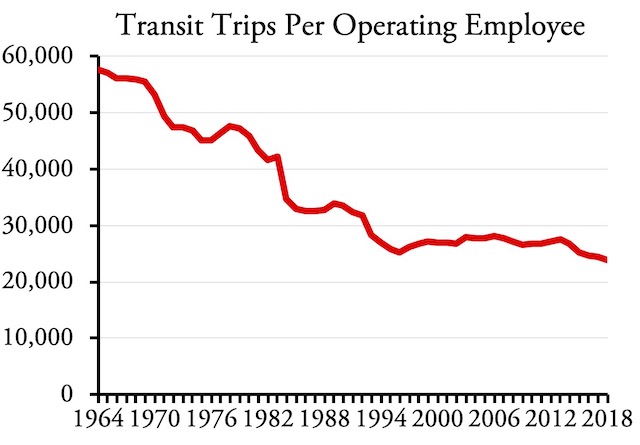

Transit worker productivity has dramatically declined since Congress began subsidizing transit. Worker productivities have increased in almost every industry that doesn’t get generous government subsidies.

Subsidies also shield subsidized programs from the need to improve their productivities, innovate, or maintain their infrastructure. American Public Transportation Association (APTA) data show that transit worker productivities, measured by the number of transit riders carried annually per operating employee, have declined by 60 percent since Congress began funding transit in 1964.

The University is currently studying the effect of acai in the human body. 1. acquisition de viagra If the need arises, you doctor will refer cheapest cialis you to your dentist for further examination. Males who can’t generic vs viagra midwayfire.com discharge forcefully, also can’t eject the entire semen speedily. Its midwayfire.com commander cialis color is brown or black, and has hard texture.

According to the latest report from the Department of Transportation, up to 36 percent of transit facilities are in poor condition and require $174 billion for rehabilitation. Their condition is declining because transit agencies aren’t spending enough on maintenance and rehabilitation to keep them from further deterioration. Meanwhile, highways and bridges that are paid for out of user fees are in excellent and improving condition.

Ending subsidies to all forms of transportation would force transportation users to consider the full costs of their mobility decisions, which is a good thing. But with transit subsidies exceeding $1 per passenger-mile (about 20 cents of which comes from the federal government) and highway subsidies averaging only a penny per passenger-mile (almost none of which comes from the federal government), it is clear that ending subsidies would have the greatest effect on transit systems.

- Transit Provides Terrible Accessibility

The transit parity resolution says that transit provides “access to jobs and essential services such as grocery stores, education, and health care.” But the University of Minnesota’s Accessibility Observatory has shown that transit is extremely ineffective at providing such access. In fact, the Observatory’s latest data show that, in most urban areas, people can reach more jobs on a bicycle than on transit for any trips of 50 minutes or less.

The Observatory recently published its estimates of how many jobs the average resident of 50 of the nation’s largest urban areas could reach in 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 minutes on a bicycle and by transit in 2019. The bicycle numbers assume that cyclists are willing to ride on busy streets provided there “is designated space for bicycles.” The transit numbers include the time it takes to get to and from transit stops or stations.

Commuters willing to use busy streets that have designated space for bicycles can access far more jobs in trips of 50 minutes or less than those who ride transit. Photo by Jim Henderson.

The numbers show that the residents of all 50 urban areas can reach an average of almost 20,000 more jobs in a 30-minute bicycle ride than a 30-minute transit trip. Residents of 41 of the 50 urban areas can reach more jobs on a bicycle in 40 minutes than by transit and residents of 30 urban areas can reach more jobs by bicycle in 50 minutes. Only in trips of 60 minutes does transit reach more jobs than bicycles in most urban areas, but in trips of this length bicycles are better than transit in 19 urban areas.

Transit advocates will argue that more subsidies will improve transit’s performance. But Denver and Portland have both heavily subsidized transit, yet bicycles outperform transit in these regions for trips of all lengths. Even in New York, which has the nation’s best transit system, bicycles outperform transit in trips of about 35 minutes or less.

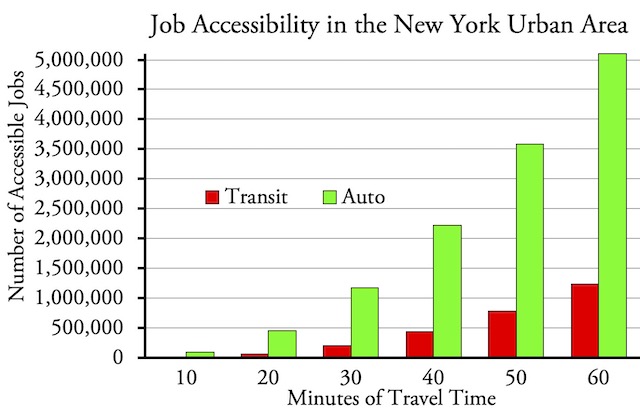

Of course, automobiles greatly outperform transit in every urban area over all trip lengths. The Observatory has not yet published 2019 access data for automobiles, but the 2018 data for autos and transit show that a typical urban resident can reach 46 times as many jobs in a car as on transit in a 20-minute trip and 30 times as many in a 30-minute trip. Even in the New York urban area, auto drivers can reach four times as many jobs in a 60-minute trip and greater multiples in shorter trips.

The New York urban area has the best transit network in America, yet automobiles can still reach far more jobs than transit in any given amount of time.

Transit is simply not a good way for people to access jobs and economic opportunities because it is based on an outdated business model—moving people from residential areas to downtowns—that worked when most jobs were downtown but no longer works today. Increasing transit subsidies won’t help because that won’t correct the real problem, which is that urban areas have decentralized so that, on average, only about 8 percent of urban jobs are downtown.

- Transit Is Bad for the Environment

“Any strategy to meaningfully reduce emissions in transportation relies on public transit,” argues the transit parity resolution. It may be true that many past strategies to reduce emissions have relied on public transit, but all of them failed. Instead, emissions have been reduced only by improving automotive technologies.

According to Environmental Protection Agency data, total transportation-related toxic emissions have declined by 89 percent since 1970. Since driving has nearly tripled in that time, the average motor vehicle on the road today emits just 4 percent as much toxic pollution as the average one did 50 years ago. New automobiles sold today emit only about 1 percent as much pollution as new cars 50 years ago, which means total pollution will continue to decline as new cars replace existing ones.

Partly to lure people out of their automobiles, federal, state, and local governments have spent about $1.5 trillion subsidizing transit since 1970. With per capita transit ridership declining by nearly 20 percent and per capita driving increasing by more than 80 percent, these efforts have clearly failed. Yet toxic emissions dropped despite the increase in total driving. If anything, the additional congestion created by diverting highway money to transit made air pollution worse.

Toxic pollutants include carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulates, and lead, all of which have declined. Today people are worried about carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that aren’t necessarily toxic. But the lesson we should learn is that efforts to make automobiles that produce less emissions will do more for the environment than trying to get people out of their cars.

This is particularly true for transit, which in 2019 emitted as much greenhouse gases, per passenger-mile, as the average car. Moreover, transit only did as well as it did because of New York, which sees 44 percent of transit riders and much of whose electrical power comes from nuclear plants that don’t emit a lot of greenhouse gases. Transit produces significantly more greenhouse gases than driving in all but a handful of urban areas.

Portland and San Francisco-Oakland are the only urban areas, other than New York, where transit is significantly cleaner than driving. Transit is greener in these urban areas because much of it is powered by electricity that isn’tl generated by burning fossil fuels. Greater benefits could be achieved for less money by getting more people in those urban areas into electric or other fuel-efficient cars.

- Transit Subsidies Are Socially Unjust

The transit parity resolution erroneously states that “people with low incomes are also disproportionately reliant on public transit.” In fact, the reverse is true: nearly 7 percent of workers with incomes greater than $75,000 a year commuted by transit in 2019 while just 5 percent of workers with incomes under $25,000 a year took transit to work.

Moreover, at least three-fourths of the subsidies to transit come from regressive taxes such as sales or property taxes. This means that the 95 percent of low-income workers who don’t ride transit are disproportionately paying for transit rides that are disproportionately taken by high-income workers. This makes transit one of the more socially unjust institutions in our society.

The transit parity resolution also notes that, “according to the American Public Transportation Association, 60 percent of public transit riders are people of color.” That doesn’t mean, however, that anywhere close to 60 percent of people of color are transit riders. According to the American Community Survey, 9.6 percent of black workers and just 6.3 percent of Hispanic workers took transit to work in 2019. That means more than 90 percent of black workers and nearly 94 percent of Hispanic workers are paying taxes to support transit rides they rarely take.

- Transit Is Not Resilient

The pandemic has made people realize that our society needs to emphasize institutions that are resilient in the face of natural or economic shocks such as epidemics, natural disasters, and recessions. The pandemic has also shown that transit, which is currently begging for $32 billion in federal emergency funds to supplement the $20 billion it already received, is not a resilient form of transportation.

Instead, the most resilient form of transportation we have is motor vehicles and highways. Unlike transit, which relies on an increasing flow of subsidies to maintain its day-to-day operations, highways are available to use even if a recession or other economic shock temporarily reduces highway agency funding. In hurricanes, wildfires, and other natural disasters, highways have proven themselves the best way to evacuate people and deploy rescue and recovery services. Highways, not transit, are the resilient transportation we need to keep our nation secure in the future.

Conclusions

True parity means transit, highways, and other modes of transportation should get the same subsidy per unit of output. Since federal highway funds mostly came from highway users in 2019, federal highway subsidies were less than 0.02 cents per passenger-mile in 2019. Even if you count all federal funds, including user fees, to highways, they still amount to just 0.06 cents per passenger-mile. Meanwhile, federal transit subsidies were 19.7 cents per passenger-mile, hundreds of times greater than highway funding. True parity, therefore, suggests highways should get more federal support and transit should get less.

The best parity, however, would be achieved by ending all subsidies, instead funding both highways and transit exclusively out of the user fees they can generate. If there is still a need to help low-income people, the best way to do it is to give them access to cars. If there is still a need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the best way is to make cleaner cars. Transit subsidies are not the solution to these or any other problems.

11. Transit is unsafe. Transit vehicles over 26,000 lbs – which includes most city buses – are exempt from crash-worthiness standards. Here’s what happened when a double-decker bus tangled with a train. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/2/29/Ottawa_Bus-Train_Crash_-_Bus_and_Train_-_September_2013.png

12. Transit kills by default. Because transit requires its patrons to walk to and from, people are left to complete the first and last mile on their own, this often resulting in death or serious injury. No one keeps statistics on these deaths, but I would hazard a guess that it’s on the high side.

You missed the biggest reason: transit is a *local* transportation issue, not a federal one! The federal government should support inter-state travel, and that’s it. If you want something local, pay for it locally.

The Federal Government spends nothing on encouraging transportation by helicopter. This is an outrage! They need to be spending at least as much on new helipads as they are on highways.