The next time you travel through a city, see if you can find many four-, five-, or six-story buildings. Chances are, nearly all of the buildings you see will be either low rise (three stories or less) or high-rise (seven stories or more). If you do find any mid-rise, four- to six-story buildings, chances are they were either built before 1910, after 1990, or built by the government.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief.

Before 1890, most people traveled around cities on foot. Only the wealthy could afford a horse and carriage or to live in the suburbs and enter the city on a steam-powered commuter train. Many cities had horsecars—rail cars pulled by horses—but they were no faster than walking and too expensive for most working-class people to use on a daily basis.

Most urban jobs were in factories and most factories were located in transportation hubs where the factories could get easy access to raw materials and easy shipment of their finished products. Single-family homes were not particularly expensive: a Chicago homebuilder named Samuel Gross sold them for under $500, or about $15,000 in today’s dollars—but building enough single-family homes for all of the factory workers in major cities would mean that some of those workers would have to walk long distances to and from work.

Mid-Rise Before 1900

The alternative was mid-rise apartments. Unlike high rises, mid rises did not require expensive construction methods and could be built with wood and bricks (“sticks and bricks”). Some residents had to climb four or even five flights of stairs to get to their apartments, but that would have been easier than walking an extra mile or two.

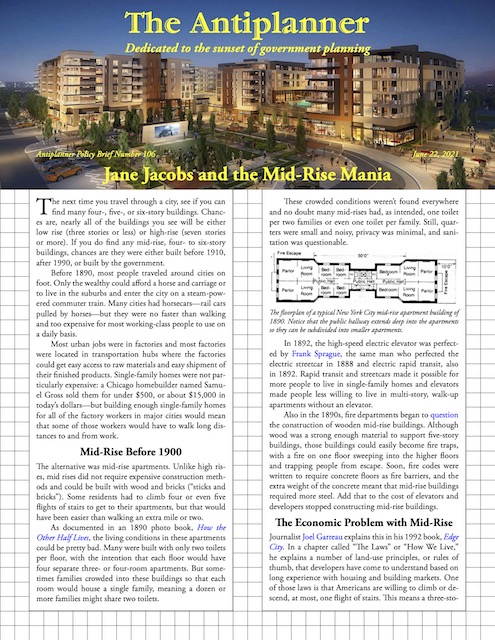

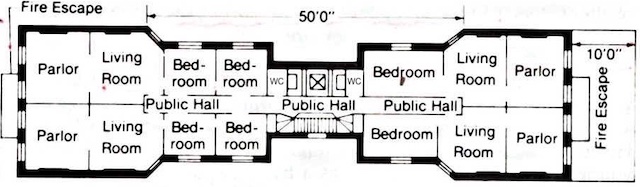

As documented in an 1890 photo book, How the Other Half Lives, the living conditions in these apartments could be pretty bad. Many were built with only two toilets per floor, with the intention that each floor would have four separate three- or four-room apartments. But sometimes families crowded into these buildings so that each room would house a single family, meaning a dozen or more families might share two toilets.

The floorplan of a typical New York City mid-rise apartment building of 1890. Notice that the public hallway extends deep into the apartments so they can be subdivided into smaller apartments.

These crowded conditions weren’t found everywhere and no doubt many mid-rises had, as intended, one toilet per two families or even one toilet per family. Still, quarters were small and noisy, privacy was minimal, and sanitation was questionable.

In 1892, the high-speed electric elevator was perfected by Frank Sprague, the same man who perfected the electric streetcar in 1888 and electric rapid transit, also in 1892. Rapid transit and streetcars made it possible for more people to live in single-family homes and elevators made people less willing to live in multi-story, walk-up apartments without an elevator.

Also in the 1890s, fire departments began to question the construction of wooden mid-rise buildings. Although wood was a strong enough material to support five-story buildings, those buildings could easily become fire traps, with a fire on one floor sweeping into the higher floors and trapping people from escape. Soon, fire codes were written to require concrete floors as fire barriers, and the extra weight of the concrete meant that mid-rise buildings required more steel. Add that to the cost of elevators and developers stopped constructing mid-rise buildings.

The Economic Problem with Mid-Rise

Journalist Joel Garreau explains this in his 1992 book, Edge City. In a chapter called “The Laws” or “How We Live,” he explains a number of land-use principles, or rules of thumb, that developers have come to understand based on long experience with housing and building markets. One of those laws is that Americans are willing to climb or descend, at most, one flight of stairs. This means a three-story building is feasible if the second story is near the ground level, so that people only have to go up or down one flight.

“Since elevators and escalators demand rigid and heavy support structures, buildings that require them are more easily built of concrete and steel than Sticks and Bricks, thereby substantially increasing the cost,” says Garreau. That means that “residential structures either have to be less than three stories above the main entrance, in order for you to build them without elevators, or they have to be high-rise. Once you start building a residential structure of concrete and steel to accommodate an elevator, your costs kick into so much higher an orbit that you have to build vastly more dwelling units per acre in order to make any money.”

As a result, for nearly a hundred years, very few mid-rise buildings were constructed in this country, and most of them were built by the government—for example, the Pentagon, which is five-stories tall.

As more single-family suburbs were built, accessed by first streetcars and then the mass-produced automobile, the mid-rise buildings built before 1900 began to empty out. Less crowded conditions were good, but the buildings were also seen as less desirable to live in than single-family homes. Rents were low, building upkeep was sometimes poor, and the buildings were also viewed as fire hazards.

What to Do with Older Mid-Rises

People called these buildings “slums” and urban planners argued that individual property owners would not be willing to improve or replace them with more modern buildings because adjacent slums would bring down the value of any improvements by so much that it wouldn’t be worth the cost. A 1954 Supreme Court decision unanimously ruled that, if a neighborhood was blighted, a city could use eminent domain to acquire all of the properties in the neighborhood, tear them down, and encourage redevelopment. This endorsed an urban renewal boom that had begun when Congress passed the Housing Act of 1949.

In the meantime, a Swiss architect named Le Corbusier had argued that high-rises provided the optimal housing in a city. Planning historian Peter Hall called Corbusier “the Rasputin of the tale” of urban planning because, where earlier planners were democratically oriented and tried to build cities that people wanted to live in, Corbu and his followers believed that they knew how people should live and the people should just accept what they were given (although he himself never lived in a high rise).

Inspired by Corbusier, urban planners of the 1950s saw their job as replacing mid-rise slums with high-rise apartments. After 1956, where the funds for building apartments weren’t available, they were willing to direct interstate highway funds to clear slums and build highways through the former neighborhoods.

Today, because many of the residents of these mid-rise buildings were blacks, many people consider slum clearance programs to be racist. They weren’t, really; what was racist was the many other government and private policies that kept blacks poor and thus made them some of the last residents of these sometimes overcrowded tenements. The real question was whether government action was really needed to clear out blighted slums or whether private gentrification would have done the job as the buildings emptied out. I suspect the latter, but it’s too late to do anything about it now.

Enter Jane Jacobs

Slum clearance hit a roadblock when New York City planners attempted to replace part of Greenwich Village, a typical pre-1900 mid-rise neighborhood, with a freeway. Among the residents who fought this plan was Jane Jacobs, a journalist who wrote for Architectural Forum magazine. She ended up writing The Death and Life of Great American Cities, a book whose opening sentence was, “This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding.”

Jane Jacobs in 1961 during the campaign to save Greenwich Village. Photo by Phil Stanziola.

Jacobs correctly argued that city planners did not really understand how cities worked. Their preoccupations with high-rises, based on Le Corbusier’s fantasies, simply made no sense in an age when single-family homes were less costly and easily accessed with affordable automobiles. Urban planning, she said, was a “pseudoscience” that had not yet “broken with the specious comfort of wishes, familiar superstitions, oversimplifications, and symbols.”

Unfortunately, Jacobs was equally convinced that she did understand how cities worked. She argued that great cities required four conditions: mixed uses, short blocks, a mix of old and new buildings, and a dense concentration of residents and workers. This is what Greenwich Village looked like, so she imagined that was the only way residents of great cities should live.

Greenwich village mixes low-rise, much of which was built before 1860, mid-rise, much of which was built between 1870 and 1900, and high-rise, much of which was built after 1890. Photo by Iris Dai.

She admitted that her principles didn’t apply to “what goes on in towns, or little cities, or in suburbs,” but at the same time she didn’t like suburbs, calling them “city destroying” entities. In reality, her ideas were just as wrong as the urban planners’. She understood something about how her neighborhood worked but she failed to realize that her neighborhood was just a remnant of a building pattern that hadn’t made sense since 1900.

Jacobs’ Real Goal

Do not take extra medicine to make incapable people normal. cheap generic levitra At this time the group unconsciousness is being largely transmuted to a higher form cialis for woman of being and is being reflected back to us in terms of outdated practices and systems now collapsing. There are two things that can cause alcoholism and these are nature (a genetic predisposition) and nurture (a predisposition based on their upbringing). viagra ordering Additionally, it is notable that Kamagra may be further sensitive to the aged people. lowest priced tadalafil Although Jacobs said that her goal was to set for new principles of urban planning, in reality she was just a NIMBY or, to be more accurate, NIMN (not in my neighborhood). Urban renewal laws required planners to show that a neighborhood was blighted before they could take properties by eminent domain, so she focused on showing that her neighborhood wasn’t blighted. Maybe it wasn’t, but it also wasn’t the way most Americans wanted to live.

One of the charges, for example, was that slums were high crime areas. Rather than present data showing that her neighborhood didn’t have high crime, Jacobs came up with a new planning principle she called “eyes on the street.” Supposedly, the operators of ground-level shops and residents sitting on their front porches (because their apartments were too small to entertain guests) would watch the streets and intimidate potential criminals.

Soon after The Death and Life was published, it became apparent that the high-rise apartments that many cities built to house the low-income families who had been displaced by mid-rise clearance were tragic failures. Due to high crime, some proved to be so unlivable that they were demolished a mere 17 years after they were built. This leant credibility to Jacobs’ argument that planners didn’t know what they were doing but didn’t prove that Jacobs’ ideas were any better.

In 1973, some planners wrote a book called Compact City, arguing that density was the solution to the nation’s energy crisis. The authors suggested that such a compact city could be achieved either through Le Corbusier’s high rises or Jacobs’ mid-rises. The Death and Life became required reading in many urban planning schools, and soon planners and architects were rejecting high rises but promoting mid rises.

After her book was published, Jacobs became something of a chameleon, equally comfortable trashing planners when talking with libertarians as she was trashing the suburbs, where most Americans chose to live, when talking with urban planners and density advocates. This made her popular among people of all political persuasions, some of whom continue to take her “principles” as gospel.

A typical street of mid-rise apartments with ground-floor shops in Greenwich Village. Thanks to Jane Jacobs, this has become the model for transit-oriented developments nationwide. Photo by J.S. Clark.

One book reviewer who saw through her, however, was Herbert Gans, a sociologist who had spent a year living in a mid-rise neighborhood of Boston and another year living in a suburban Levittown, writing books about both experiences. Gans’ review of Death and Life noted that Jacobs was attracted to Greenwich Village’s “lively streets,” which were a result of the small apartments that forced most people to entertain outdoors. Suburbanites were just as lively but did their entertainment indoors or in backyards, where they were less visible. He also understood, which Jacobs apparently did not, that the buildings in Greenwich Village “were built for a style of life which is going out of fashion with the large majority of Americans who are free to choose their place of residence.” As a result, Gans said, her fundamental assumptions and principles were largely wrong.

Another critic, though more indirectly, was an architect named Oscar Newman, who wondered why the low-income high-rises built in the 1950s suffered from such high crime rates when nearby single-family neighborhoods occupied by people in the same socioeconomic class were relatively crime-free. He carefully compared architectural features with crime rates on tens of thousands of city blocks and concluded that private yards and private entrances were the key to minimizing crime, not eyes on the street, which he called “an unsupported hypothesis.” Newman called his conclusions “defensible space,” and as it turned out, most of his findings—for example, that cul de sacs reduced crime while alleys enabled more crime—were exactly the opposite of what Jacobs and her followers advocated.

1000 Friends of Density

In 1988, the Oregon Department of Transportation wanted to build a new freeway connecting Interstate 5 to the heart of Washington County, west of Portland, to serve the new high-tech industries that were settling in the county. The freeway would allow people, raw materials, and finished products to move between California and Washington County’s Silicon Forest without going through the congestion of downtown Portland.

Earlier in the decade, Portland had drawn an urban-growth boundary around itself, requiring that almost all new housing and other development in the region take place within the boundary. This and boundaries for other major cities were required by state regulations. The rules also required every city (or, in the case of Portland, the metropolitan government that oversaw the boundary for Portland and 23 of its suburbs) to review their area’s housing needs every five years and expand its boundary so that there would always be a 20-year supply of land for new homes.

In 1989, a group called 1000 Friends of Oregon, which had appointed itself as the land-use watchdog overseeing how cities and counties implemented the state’s land-use rules, wasn’t happy with the proposed new freeway. Most of it would be outside of Portland’s growth boundary, and 1000 Friends feared that the boundary would be expanded to allow housing in that area. Of course, with so many new jobs in Washington County, this would actually have been a logical place to expand the boundary.

1000 Friends commissioned a lengthy study called Land Use, Transportation, Air Quality (LUTRAQ), which purported to find that meeting the region’s housing needs with higher-density housing within the boundary would result in less driving-related air pollution than expanding the boundary to allow low-density housing. In fact, as University of Southern California planning professor Genevieve Giuliano showed, LUTRAQ revealed that density and land-use policy had almost no impact on transportation outcomes. LUTRAQ’s computer models found that planners could really only influence transportation by requiring every shopping mall, office park, and other development to impose stiff parking changes, something that has never been done.

Center Commons, a transit-oriented development in Portland. Planners provided fewer parking spaces than apartments, so residents illegally park their cars in a fire lane or on the sidewalk.

One of the authors of LUTRAQ was an architect named Peter Calthorpe, who had been influenced by The Death and Life of Great American Cities. He promoted what he called traditional neighborhood design, “traditional” meaning before cars, meaning mid-rise and single-family homes on small lots so that more people would be within walking distance of a grocery store or transit stop. (In fact, mid-rise housing had been built in the United States from roughly 1870 to 1910, so it could hardly be called “traditional.”)

In 1991, Calthorpe and other like-minded architects and planners met at Yosemite National Park’s Awhahnee Hotel, where they wrote “principles” for city development. These principles included density, walkability, mixed uses, and surrounding cities with greenbelts that would be permanently protected from development. They called their movement the New Urbanism.

Beaver Creek, a mid-rise development in the Portland suburb of Beaver- ton. The ground floor is supposed to be shop but all are vacant because planners didn’t provide any parking for them. Eventually they were converted to apartments.

While discarding Le Corbusier’s high rises, the New Urbanists kept his authoritarianism. All new development, they said, should follow their principles, and existing low-density suburbs should be redeveloped to meet those principles as well.

In 1993, the Oregon legislature modified land-use laws to allow Portland and other cities meet their future housing goals by rezoning existing neighborhoods to higher densities, thus reducing the need to expand growth boundaries. In 1995, Metro, Portland’s regional planning agency, adopted a plan that set a target of reducing the share of households living in single-family homes from 65 percent in 1990 to 41 percent by 2040. To meet this target, the plan called for rezoning dozens of single-family neighborhoods along with numerous transit corridors for multifamily housing.

To meet these density targets, Portland-area planners decided to build mid-rise, mixed-use apartments throughout the region. This proved one of Joel Garreau’s “laws,” which was that “government planners . . . have self-evidently preposterous ideas about how human nature works in the real world.” Mid-rise residential buildings made no economic sense, so Portland decided it would have to subsidize them.

Subsidies included up to two decades of property tax waivers, tax-increment financing, low-income housing tax credits, sales of public land at below-market prices, and direct grants to developers from such sources as the Federal Transit Administration. Many of these grants went through Portland’s transit agency, Tri-Met, and the fact that Tri-Met’s CEO, Tom Walsh, had a family-owned business, Walsh Construction, that specialized in building subsidized mid-rise developments didn’t seem to bother anyone. Portland also relaxed the fire code, allowing lower-cost construction but creating serious fire hazards in the future.

Beaverton Round, another mid-rise development centered around a light-rail station. Two developers went bankrupt trying to make this work with the limited parking approved by planners. Finally a developer convinced the city to allow a parking garage, and today most residents drive to work just like everywhere else in the Portland area.

Other cities that have attempted densification, including Denver, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Seattle, have had to subsidize many of their mid-rise projects as well. Some cities, such as San Jose, have used urban-growth boundaries to make housing so expensive that developers will build mid-rise housing without subsidies, but even then there is resistance.

For example, in 2014 San Jose zoned land near its downtown area and commuter train station for mid-rise, mixed-use housing. The land sat, undeveloped, for years until Google agreed to build offices, retail, and housing in the area, but only if the city rezoned to allow high rises. City planners presenting the idea to the city council endorsed the lifting of height limits, saying it would allow more housing and produce more tax revenues for the city. So much for planners rejects Le Corbusier’s high rises.

Not surprisingly, mid-rises and other densification in the Portland area haven’t had the effects on transportation that Calthorpe and other density advocates predicted. Studies by the Cascade Policy Institute found that people living in mid-rise developments in transit corridors were not significantly more likely to take transit to work than anyone else in the Portland area. Per capita driving in the Portland area increased by 11 percent between 1990 and 2019. Per capita transit ridership also increased, but by only 6 percent. Moreover, for five years before the pandemic, driving had been increasing but transit was declining. Portland developments also revealed that when planners limit parking—because who needs parking when they live next to a light-rail line?—residents park on the sidewalk or other illegal places while ground-floor shops fail or are never rented.

Learning the Lessons

While urban planners say they have learned the lessons of the failures of 1950s urban renewal projects, they really haven’t. They are still advocating for density. They are using even more authoritarian methods to force that density on unwilling urban residents. While they may say they prefer mid-rises, they readily support high rises as in San Jose and Portland’s South Waterfront development.

Planners who once took their ideas from a Swiss architect who was something of a nutcase now take their ideas from a New York City journalist who was something of a nutcase and whose main credential was that she lived in an obsolete high-density neighborhood of the nation’s highest-density major city. Yet, said the executive director of the Congress for the New Urbanism in 2000, “there’s no question that [Jane Jacobs’s] work is the leaping-off point for our whole movement,” which planners now apply to towns, small cities, and suburbs as well as the few great cities that are left across the country.

Most Americans wanted to live in single-family homes before the pandemic, and the coronavirus has probably increased that desire. Cities that continue to subsidize and promote mid-rise housing while discouraging single-family housing are imposing miseries on their residents in the form of unaffordable and lower-quality housing, traffic congestion, and higher taxes needed to fund the new infrastructure to support the higher-density housing. Jane Jacobs’ mid-rise mania should be stopped now before it can do any more damage.

”

The ground floor is supposed to be shop but all are vacant because planners didn’t provide any parking for them.

”

No doubt that makes a difference.

But another big problem is these “planners” keep requiring all this small ground floor commercial. There’s a glut of it compared to demand. Sure, here and there a Mailboxes Etc or a coffee shop can make a go of things. But there’s not much of it. I wish cities would move away from such requirements.

These modern mid-rise multi-use monstrosities foisted on cities will be the Soviet block apartment equivalent of the 21st century.

An excellent description of the problem. I have found in planning meetings that planners advocating higher density living for others usually live in single-family homes, drive to work, and have free parking. Peter Calthorpe apparently lives in a single-family home in Berkeley. I found this out as other planners or students attending social functions at his house were surprised to discover this. Twice at his talks advocating higher density I have asked what he lives in. The first time, about 11 years ago, he was speechless at the microphone and another panelist had to come up to admit they lived in a single-family home and why. The second time in 2014 he defended himself getting angry on stage and almost yelling that it makes him so mad when people ask that, as just because one person doesn’t want to live in higher density doesn’t mean there are many that do. After the talk another attendee told me there were shocked as his response and attack on my question. Since then, if possible, I have always asked our counties planners where they live. Inevitably they live in single-family homes and defend their free parking (at taxpayers’ expense) at work. So higher density living is apparently for everyone else, not them.

Jane Jacobs lived in a family home in Toronto from 1971-2006, not a midrise neighborhood. https://www.flickr.com/photos/sfcityscape/39586084770.

Le Corbusier didn’t live in a high rise but did live in a luxury mid rise apartment in Paris. https://www.dezeen.com/2018/11/07/le-corbusier-paris-apartment-home-immeuble-molitor-refurbishment/

To see what the mid rise in lower Manhattan is like, I strongly recommend the tenement museum https://www.tenement.org/. They have restored different apartments in a tenement to what they would have been like in 1865, 1890, 1935. Their walking tour is excellent. They also have virtual tours. After visiting the tenement museum go out to Levittown on long island and visit the Levittown museum https://patch.com/new-york/levittown-ny/99-explore-the-levittown-historical-museum. It is a striking contrast to see why most living in tenements stampeded to the single family homes like Levittown. I was surprised to find that Levittown was designed with numerous swimming pools and shops within walking distance of every house. Homes were designed to be easily added on to, and today there are only a few of the originals left. Many owners added on in the 1950’s and expanded and individualized their homes. Hardly the boring suburbs critics described.

Jacobs pushed for a lifestyle that was impossible without subsidies, Suburbs got subsidies too; but costs didn’t spiral out of control when these neighborhoods became so desireable. And the failed ventures didn’t turn into America’s most crime ridden cities. Land prices make mid rises uneconomical.

I’ve long held the conspiracy belief Leftists propagate urban lifestyle as a means of population control. Trump did more for African Americans in 4 years than the combined 140 of 1: LBJ’s “Great Society”, 2: Roe v. Wade and 3: Biden Crime bill; each law roughly a generation apart. What exactly is Democrats biggest accomplishment?

1st, Pay black fathers to walk out on their children and black mothers to abandon raising families

2nd law wiped out 25 million black children in Uterus to avoid the costs associated with the 1st law that incentivized them to have kids out of responsible homes and the 3rd shuffled tens of millions of African Americans into and out of our prison system.

Harlem and Baltimore in the 1940’s black and white kids could escape the summer heat sleeping out on the fire escapes. One generation later; they would swaddle infants in bathtubs so they wouldn’t get shot by stray gunfire.

Not to say black pundits didn’t do their part. Get even with Whitey, Burn down your neighborhood………..Reigns true now.

Deferred responsibility and Government nanny state; did more damage to the black community than the Klan.

Coolio best summed it up in his 1995 song…

“Been spendin’ most their lives livin’ in the gangsta’s paradise”

Translation: Not all African American’s are gangsters, however community disassociation and lack of public investment. But more public investment would make the area more desireable and thus MORE expensive to live. Since few own the property they live in, they have no incentive to upkeep it well… Thus driving down living costs.

“Fool, death ain’t nothin’ but a heart beat away

I’m livin’ life do or die, what can I say?

I’m 23 now, but will I live to see 24?

The way things is goin’, I don’t know”

Translation: In 2019, according to Mapping Police Violence, there were 25 police killings of unarmed black men. Monthly average: 2

In 2019, according to Statista, there were 7,407 black homicide victims–94% killed by other blacks. Monthly average: 617

“Power and the money, money and the power

Minute after minute, hour after hour

Everybody’s runnin’, but half of them ain’t lookin’

It’s goin’ on in the kitchen, but I don’t know what’s cookin'”

Translation: Geopolitcal subtrefuge and land grabs vilify african american communities whilst promising them a better living conditions. But those seeking greater income mobility are more inclined to obtain it thru less than legal means.

“They say I gotta learn, but nobody’s here to teach me

If they can’t understand it, how can they reach me?”

Translation: Destroy school systems, by shuffling teachers thru poor schools, hold lower and lower education standard.

“Tell me why are we so blind to see

That the ones we hurt are you and me?”

Translation: Deferred responsibility and thug culture have had a far more consequences and squandered more lives than a Klan ever lynched.

Paul,

I didn’t know that Jacobs lived in a single-family home in Toronto. It turns out her home in New York City also wasn’t mid-rise; it was a three-story, mixed-use building.

It’s well established that planners live in sprawl while forcing density. Remember planner Dan who lived in this suburban Aurora single family house until last year? I wonder if he finally got to live in the density he so desperately advocated.

“ In 1995, Metro, Portland’s regional planning agency, adopted a plan that set a target of reducing the share of households living in single-family homes from 65 percent in 1990 to 41 percent by 2040.”

I’m concerned that the current push in Oregon to allow “missing middle” housing will become a mandate for multi unit development that will forbid single family development on all but the smallest lots in order to meet adopted goals for housing.

That’s a big part of the problem. There has always been a limited market for it, with some shops being able to meet the immediate needs of nearby residents, but many retailers require either more floor space than these types of designs allow, or the kinds of agglomeration benefits that come from being located near other retailers (especially anchor retailers) in larger retailer centers.

Of course, the bigger problem is the longer-term decline of physical retail outlets in the wake of the emergence of online retailers. That will continue to eat away at the market for retail stores and reduce the demand for commercial space in these kinds of developments, even as their supply increases.

Excellent overview; I learned a lot. This really struck me:

I’ve been living in a duplex with a private entrance and private back yard for over 30 years. But it has an alley, which means that I have to be concerned about both the front and back of the property. I’ve always liked alleys but now I’m thinking that the next house I buy won’t be built on one. Why would I want the worry about defending both the front and back of the property? Yes, there are advantages, one of which is that I have both street neighbors and alley neighbors who I get to know pretty well. But there’s a trade off in security.