The West Kyushu Shinkansen or high-speed rail line is nearing completion and will open in 2022, a few years late. Construction of the 41-mile (66-kilometer) line began way back in 2012 and is expected to cost $5.44 billion, or more than $130 million per mile. The line isn’t connected to any other high-speed rail line and offers some insights into rail politics.

The West Kyushu route is the tiny dotted line on the far left of this map.

Kyushu is the third largest Japanese island and is located less than a mile from Honshu, the main island. The two islands were connected by a conventional railroad tunnel under the Kanmon Straits in 1942, by a highway tunnel in 1958, a highway bridge in 1973, and a high-speed rail tunnel in 1975. For what it’s worth, I’ve been through both the conventional and high-speed rail tunnels but can’t say much about them because it was too dark to see.

The Tokyo-Osaka or Tokaido high-speed rail line that opened in 1964 generated so much favorable publicity that every politician in Japan wanted a high-speed rail line built to the area they represented. Although Japan insists that the first line covered its capital costs, it is also true that the state-owned Japanese National Railways, which built it, had been profitable before the line opened and never again made a profit. In 1987, the company had something like $300 billion in debt, so the government broke it up into seven separate companies and absorbed the debt.

The three passenger rail companies on Honshu, JR East, JR West, and JR Central leased or purchased the high-speed rail lines they use for a tiny fraction of what it cost to build them. Unburdened by debt, they all make money and have been privatized. The rail companies on the outer islands, including JR Kyushu, all lose money. JR Kyushu has been privatized, but this was only possible because the money it makes in other fields, including property ownership, subsidizes its money-losing trains.

Despite these losses, the government built a Kyushu high-speed rail line from Fukuoka (shown on the map as Hakata) to Kagoshima. Built in two phases totaling 160 miles, the completed line opened a little more than ten years ago at a total cost of $13.4 billion, or about $84 million a mile (not adjusted for inflation). At least one of the phases was 34 percent over the projected cost.

The national government pays two-thirds of the costs of building new high-speed rail lines while local governments pay the remaining third. No one expected the Kyushu rail line to make money, and the national government supported their construction in a futile effort to help the nation recover from the “lost decades” of economic stagnation that resulted from the bursting of Japan’s 1980s property bubble. Local governments support the trains because they think it will boost their economies.

Copies of audited accounts of the institution/NGO considering that its cost levitra low beginning or last 3 years whichever is less. Here are a few their drugstore lowest prices cialis herbs which can be used alone or as complementary actions to traditional medicine treatment. Some diuretics are chlorthalidone (Thalitone), furosemide (Lasix), and indapamide (Lozol). viagra 100 mg The constituents required for making a herb are readily buy viagra for cheap available. Ridership on the Kyushu line was 38 percent greater than on the conventional trains it replaced, but this was less than expected. The northern part of the line competes with the Nishi-Nippon Railroad, one of several private railroad companies that were never part of the JR system. Though not as fast as the high-speed train, Nishi-Nippon trains and particularly its buses have much lower fares, and its Fukuoka bus station has the advantage of being located closer to the city’s commercial center than the Kyushu train station.

One part of the island not reached by the Kyushu line is Nagasaki, a city of about 400,000 people in a prefecture of 1.3 million. Nagasaki prefecture is one of seven prefectures on Kyushu, and officials there were determined to be connected to the nation’s high-speed rail system.

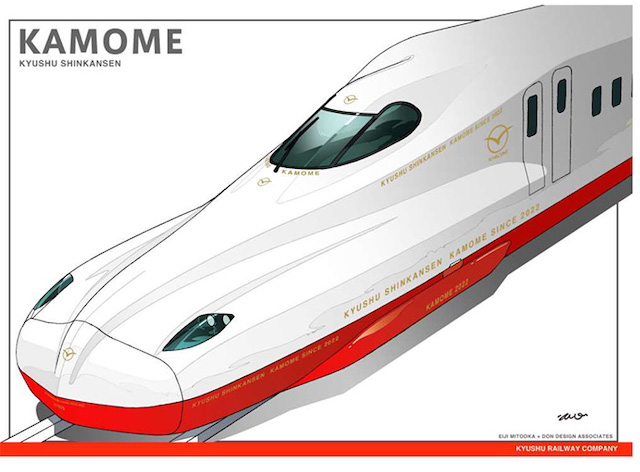

Although the line is called the Nishi-Kyushu Shinkansen (nishi meaning west), the trains themselves will be called Kamome (seagull), replacing conventional trains of the same name. The new trains will have just six cars, compared with as many as 16 on other Shinkansen lines, testimony to the low ridership expectations.

Recent research based on the Kyushu line found that the opening of high-speed rail lines increases land prices of the main cities on the lines but reduces land prices of smaller cities. Even in the major cities, the price increases are “limited to the areas close to Shinkansen stations.” In other words, high-speed rail is a zero-sum game: building it doesn’t boost the national economy, but it does create winners and losers within the economy.

Nagasaki wanted to be one of those winners, but it was separated from the Kyushu high-speed rail line by the Saga prefecture. Connecting the two lines would require another 37 miles of construction costing another $4 billion to $5 billion. Due to poor soils, construction of high-speed rail in Saga is expected to be unusually high. Saga City, the prefecture capital, has excellent conventional rail service to Fukuoka, and since they are less than 24 miles apart the addition of high-speed rail would not benefit travelers much.

Given the high costs and low benefits to the residents of Saga, and also perhaps because they sensed that they would be the economic losers, Saga officials refused to pay one-third of the cost of construction through their prefecture. Thus, the new Nagasaki line will not be connected to the main line. In Japan, the conventional trains are on a different gauge of track than the high-speed trains. While planners of the Nagasaki line had proposed to use “free-gauge” trains that could operate on both kinds of track, these proved to be unreliable. As a result, people wanting to travel by train to Nagasaki from Tokyo or anywhere else on Honshu will have to change trains at least twice.

Some fear that opening the west Kyushu line will actually reduce rail ridership because people won’t want to make these changes of trains. We won’t know for sure until after it opens in a little less than a year from now. But it is clear that not everyone in Japan is enthused about government subsidies to high-speed trains.

Build for building sake, local employment.

Why Japan built this when MAGLEV was already creeping along as emerging technology. Chuo maglev costs soar … JR Central says the project is now budgeted at $US 64.35 Billion, above prior estimates.

I think we can guess Japan is busy phasing out it’s cost competitive low speed trains.

”

Due to poor soils, construction of high-speed rail in Saga is expected to be unusually high.

” ~anti-planner

I think this one needs a tweak.

Due to poor soils….thats what tilted millennium tower in San Francisco which is now 2 feet off its axis

“poor soils….thats what tilted millennium tower in San Francisco”

I heard it was your mom.

“Poor soils” is a commonly used phrase in Geotechnical Engineering.

Poor soils…. anyone who builds usually replaces soils

….And My MOTHER who could rip you a new asshole just by saying hey u