Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack and Forest Service Chief Randy Moore have announced a new strategy to fix the nation’s wildfire crisis. Not surprisingly, the most important part of that strategy is to give them a lot more money.

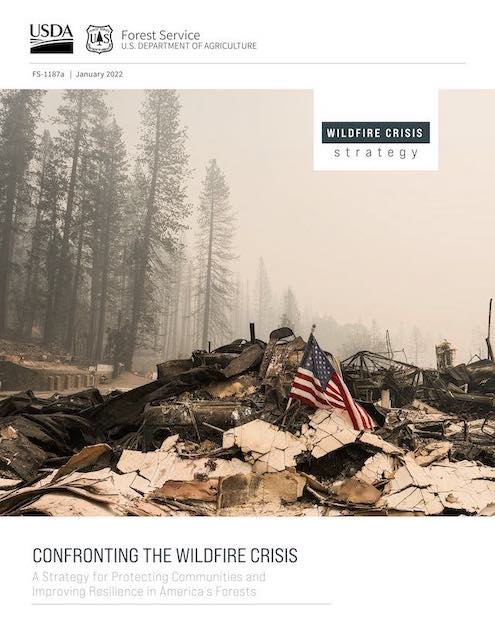

Click image to download a 34.0-MB PDF of this report.

Click image to download a 34.0-MB PDF of this report.

The Forest Service plan, if it could be called that, consists of two simple steps: 1. Give them enough money to do 5 million additional acres of hazardous fuel treatments a year for ten years. 2. By the time that ten years is up, they promise to write another plan for the next ten years.

There are a lot of problems with this plan, but let’s start with the fact that wildfire affects lots of places, but their plan focuses on just a few. The plan is based on the fundamental proposition that decades of fire suppression have led to a build up of hazardous fuels that normally would have burned if Smokey Bear hadn’t stopped the fires. Those fuels now contribute to catastrophic wildfires that burn lots of homes and other private property.

There is some truth to this proposition, but as a map on page 29 of the plan shows, it really only applies to a limited amount of land in the West. Most of the West consists of forest types that don’t accumulate hazardous fuels when left unburned, mainly because local climate allows the burnable fuels to rot away faster than they can accumulate.

For example, the Beachie Creek and Holiday Farm fires that burned more than 350,000 acres in Oregon in September 2020 destroyed more than 2,000 homes and other structures and killed six people. Yet none of the acres burned were forest types that accumulate hazardous fuels. The Forest Service’s plan would have done nothing to stop those fires.

A second problem has to do with cost. According to recent Forest Service budgets, the agency spent $430 million treating fuels on 3.2 million acres in 2018; $435 million treating 2.9 million acres in 2019; and $445 million treating 2.65 million acres in 2020. Despite rising budgets, the number of acres treated declined each year. After adjusting for inflation, costs rose by 21 percent in just two years.

Treating 5 million more acres a year means increasing spending by almost 200 percent, from $445 million to $1.3 billion a year, and that’s only if costs don’t rise any further. Frankly, I suspect costs per acre have grown because Congress has been so generous with funding that the Forest Service is careless in how it spends the money. This problem won’t be fixed by giving it even more money.

A third problem has to do with the real goal of this spending. Judging from the many photos of burnt and nearly burnt homes in this report, that goal is to protect homes and other private property. But, as my policy brief earlier this week showed, a major part of the problem is that local communities are not designed to be fire resistant. In fact, under the zoning laws in California, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, many local communities are not allowed to be fire resistant.

The Forest Service report offers three short paragraphs suggesting that the agency will promote “fire-adapted human communities.” This means it will “work with partners to help communities write community wildfire protection plans and to help homeowners prepare for wildfires by reducing fuels on their properties and creating defensible space around their homes.” Those are good things, but considering that this appears on page 38 out of the 48 pages in the report (and the pages after it are mostly photos), they are apparently low on the agency’s priority list when they should be the first priority.

If local communities can adapt to fire by making themselves fire resistant, then Congress won’t need to triple the Forest Service’s hazardous fuels budget. That would be good for taxpayers and good for communities near national forests, but it wouldn’t necessarily be good for the Forest Service’s budget, which is probably why it wasn’t a major part of the plan.

Publishing this report creates a win-win situation for the Forest Service. If Congress doesn’t fund it, the Forest Service will be able to blame Congressional stinginess for all future fires and homes destroyed by those fires. If Congress does fund it, there will still be big fires and homes burned every year, but the agency will get between $500 million and $1 billion a year added to its budget.

This follows a Forest Service tradition going back to at least 1908, in which the agency promises that, if only it had enough money, it would be able to stop the fires. In reality, the fires will never stop, and the solution is for people of the West to learn to live with them as cost-effectively as possible.

Fire’s role in dryland ecology is well known and researched, It substitutes the role normally reserved by decomposers like bacteria and fungi. In more humid and wetter environments they break down wood/plant matter into soluble nutrients for plant uptake. In xeric ecosystems this process is less efficient or virtually non-existant. So fire substitutes that role by charing material into water soluble ash.

It’s not climate change responsible for these catastrophic fires; it’s land and water use practices. Ignore them at your peril…

West of the Mississippi river, lands tend to be dryer and fires more periodic. States have ignored water stress for decades…

However there are some shorter term methods.

Rainwater harvesting An inch of water over an acre of land produces 27,000 gallons of water. So 1000 square foot roof collects 623 gallons per inch of rainfall.

Well pit recharge

Flood based recharging pits like above

Desalination Co-ops (Agree to cover partial cost of plant construction/operation in exchange for percentage of water)

Harvesting agricultural runoff

Re-forestation programs.

microcatchment . (Landscaping features) The name Zai pits refers to small pits are dug in which seed of annual or perennial crops are planted. The pits They are beneficial for soil because they increase insect and worm activity which in turn leads to a higher water infiltration when it rains, these pits are fertilized with manure (Human or animal) which also stores water better than sandy/clay soils. This intervention is most suitable for flat or gently sloped terrains (0-5% gradient) with a precipitation quantity of 350-600 mm. Other designs like contour bunds, Negarim and other features catch water instead of letting it runoff and allow to infiltrate into the soil.

Dryer lands receive much more rain than we assume. The Netherlands, for example get’s an average of 650mm (25.6 inches) of rainfall per year. Where as Xeric region Monterrey, Mexico has 680mm (26.8 inches) of rainfall. So How can the Netherlands despite having less rain, but have more fertile soils (besides a cooler climate) Be it degraded farmland or some xeric regions. Rainfall in some areas is Seasonal….in water stressed areas; water falls only at a peak of the year often a few weeks. Some regions have dry/wet seasons with six months of rain. Terrain: rain falls on slopes, hills and mountains and then flows out into streams and rivers that convey its runoff water into the sea. When areas are degraded or severely eroded, there is often a soil hardpan due to decades of compaction. The downside to no-till farming is that while it prevents soil erosion; it makes soil less permeable so only 15-25% of the water enters into the soil. The rest runs away. Pre-Industrial farmers built land terraces and planted hills, modern farming eschews that. Newly built landscaping terraces collect 3x the water to infiltrate the soil.