Imagine that, on top of all our other problems, the United States had a shortage of pickup trucks. While many pickups are purchased for recreational purposes, they also play vital roles in construction, farming, forestry, and other industries. The impacts of a shortage could reverberate throughout the economy.

Click image to download a three-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a three-page PDF of this policy brief.

A California politician says he has a solution to the pickup shortage: Simply buy old pickups, scrap them, and use the materials to build subcompact cars such as the Chevrolet Spark or Mitsubishi Mirage. Full-sized pickups typically weigh twice as much as subcompacts, so this program could flood the market with two or more vehicles for every one that is scrapped. That would have to reduce the price of pickups, wouldn’t it?

The Chevrolet Spark is one the least-expensive cars in America, but with less cargo room than the cab of most pickups, it can hardly be mistaken for a light truck. Photo by General Motors.

Of course not. Subcompact cars have their place, but they are not going to provide an adequate substitute for trucks capable of carrying bales of hay, cords of firewood, or tools and materials for building a house. The markets for the two kinds of vehicles do not overlap, so having more of one won’t influence the price of the other, but scrapping pickups would only make the remaining ones more expensive.

Single- vs. Multifamily Housing Markets

No one would confuse subcompact cars for pickup trucks. Why, then, do people think that tearing down 2,200-square-foot single-family homes to make room for 1,100-square-foot apartments will make single-family homes more affordable? This is, in essence, what the movement to ban single-family zoning calls for. Clearly, many people supporting this movement fail to realize that, just as the market for subcompacts is completely different from the market for pickups, the market for multifamily housing is different from the market for single-family homes.

There are several reasons why people prefer single-family homes. Such homes provide greater privacy and residents are less bothered by noise, cooking odors, and other impacts from their neighbors. Yards offer places for people to garden and play areas for children and pets. Low-density neighborhoods have less auto traffic and congestion.

People also sense that neighborhoods of single-family homes have less crime than higher-density neighborhoods. This is not because people who live in multifamily housing are more likely to be criminals but because multifamily housing is more likely to be attractive to crime.

Groundbreaking research by architect Oscar Newman in the 1970s showed that public spaces, such as common hallways or greenspaces around developments, were a key factor in crime because there is no easy way to detect whether someone belong in those spaces or was contemplating a break in. Single-family neighborhoods are mostly private and a stranger walking in people’s backyards is easily detected and treated with suspicion. In Newman’s terminology, single-family neighborhoods are defensible space while multifamily housing generally is not.

Revealing the Single-Family Housing Preference

The first indication that Americans prefer single-family homes is by where they actually live. The 2019 American Community Survey found that more than two-thirds of American households live in single-family homes. Nearly 77 percent of households in Indiana, Iowa, and Kansas live in single-family homes, and more than 70 percent of households in 23 other states do as well.

Density advocates claim that Americans have been “forced” to live in single-family homes by zoning laws that prohibit the development of multifamily housing. If anything, the reverse is true: anti-sprawl zoning of rural areas forces people to live in multifamily housing who would rather live in single-family homes. Only a dozen states have less than the national average of single-family homes, and all of them except Illinois and North Dakota have some form of growth management limiting the development of more single-family housing.

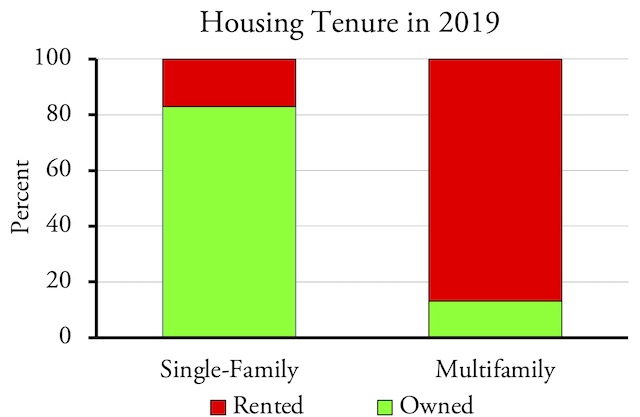

Nearly 17 out of 20 occupied single-family homes are owned by their occupants while more than 17 out of 20 multifamily homes are rented.

The second indication of the preference for single-family homes can be found in ownership patterns. The 2019 American Community Survey showed that the homeowners lived in 83 percent of occupied single-family homes while renters lived in 87 percent of multifamily dwellings.

This pattern can’t be blamed on zoning rules, which have no say on whether people buy or rent their home. Instead, most Americans appear to regard multifamily housing as temporary housing, a place for people to live who don’t expect to remain in a particular area for long or who are trying to save enough money to buy a single-family home.

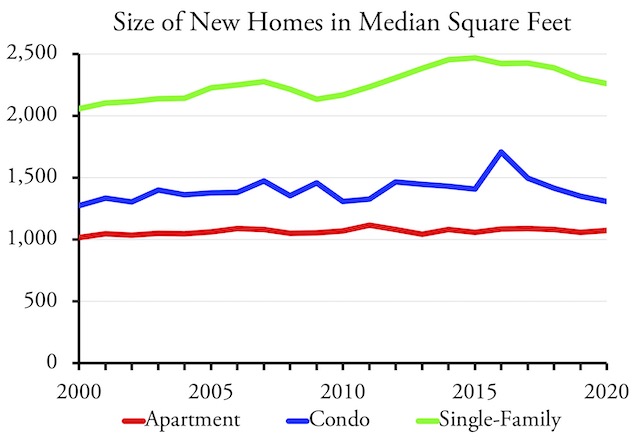

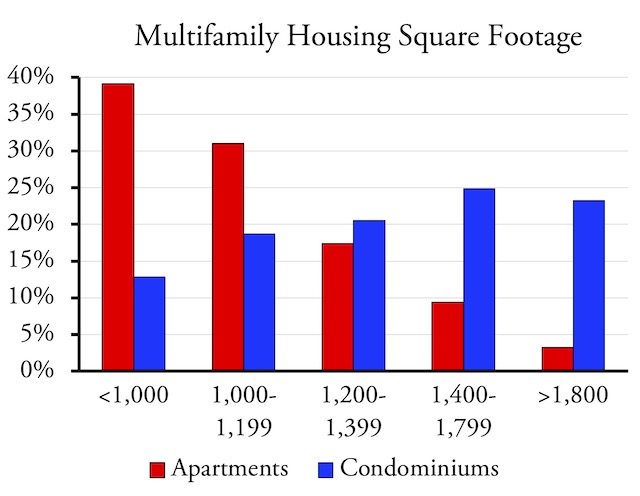

Americans buy much larger single-family homes than they rent for apartments or buy as condos. The 2016 blip in condo sizes was due to a short-lived boom in the condo market that died when it became clear that the demand for large condos was negligible.

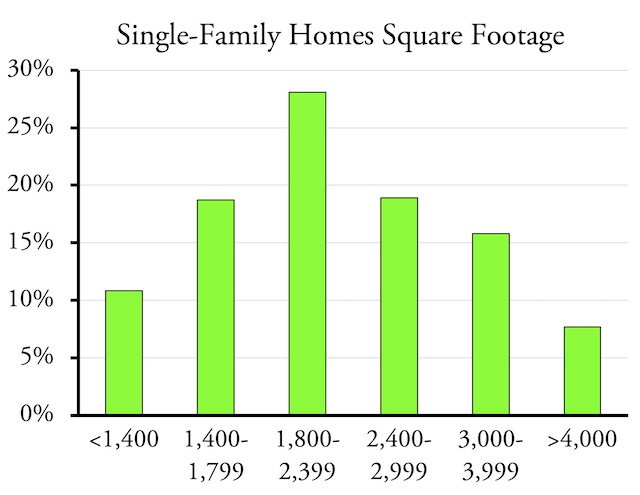

Another indication that people view multifamily housing as temporary housing is in the sizes of housing units. Census data show that the median size of multifamily dwellings built from 2000 to 2020 was 1,100 square feet, while the median size of single-family dwellings was 2,350 square feet. Only about 5 percent of multifamily dwellings were as large as the median size of single-family homes while less than 10 percent of single-family homes were as small as the median size of multifamily dwellings. Clearly, these are serving two quite different markets.

Even multifamily dwellings built as condos (that is, for owner occupancy) tend to be small. While apartments built for renting averaged 1,065 square feet, condos averaged 1,400 square feet, larger than apartments but still much smaller than single-family homes. Developers could build larger condos, but seldom do, suggesting there isn’t a demand for such housing.

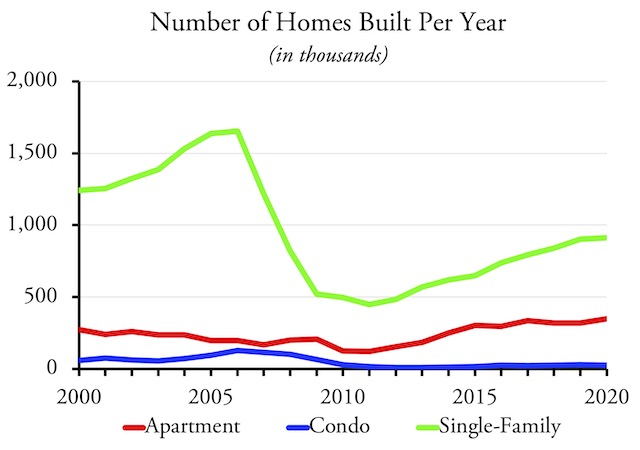

American homebuilders construct an average of about 20 single- family homes for every condo unit.

Census data indicate that median condominium sizes leaped to 1,700 square feet in 2016, then quickly fell back to 1,400 square feet. This increase was almost entirely due to a condo construction boom in Miami and one or two other Sunbelt cities, a boom that went bust in 2017, revealing developers had overestimated the market for large condominiums. The fact that a boom and bust in one or two cities can significantly affect national data reveals just how small the condominium market is: in a typical year, about 20 single-family homes are built for every condo unit.

The Affordability Lie

People like single-family homes because of privacy, yards, and other amenities, but these are reinforced by another factor: cost. Density advocates often portray multifamily housing as affordable housing, but it is only affordable because the housing units are so much smaller than single-family housing.

According to Zillow, as of March 31, 2022, the typical single-family home in the United States was worth $338,000, while the typical condominium was worth $332,000. In places that use growth boundaries or similar policies to restrict development at the urban fringe, the differences are much greater: single-family homes in the San Francisco metro area are 57 percent more expensive than condos, while in Seattle they are 63 percent more expensive.

There is very little overlap between the sizes of single-family homes built in the U.S. in the last 20 years , , ,

Condos may be less expensive, but that’s because they are smaller. Zillow once published costs per square foot of single-family homes and condominiums, but no longer does so. However, data I downloaded from 2016 indicate that the average price per square foot of condominiums was 33 percent greater than the average for single-family homes.

. . . and the sizes of multifamily homes.

According to California developer Nicholas Arenson, the higher cost is due to multi-story construction, which requires elevators and more concrete and structural steel. Two-story multifamily housing costs about the same, per square foot, as single-family homes. But a third story adds 30 to 50 percent, a fourth story doubles per-square-foot costs, and five or more stories are even more expensive. Since urban planners favor four- to six-story mid-rises, units have to be very small to be priced lower than single-family homes.

Time to End the War on Sprawl

Between 1961 and 1992, opponents of urban sprawl convinced several state legislatures and some regional planning authorities to restrict suburban development using growth boundaries, concurrency requirements, and similar policies. Effectively, they created artificial shortages of land, which in turn made housing expensive.

In response, cities and states have created a number of programs aimed at making housing more affordable, but most are in fact counterproductive. One common policy, called inclusionary zoning, requires developers to rent or sell a portion of the homes they build to low-income households at below-market prices. The developers respond by building fewer homes and charging more for the market-rate homes they do build, thus lifting overall housing prices.

Another policy is to tax new development and use the funds to build subsidized housing. The tax makes new housing more expensive and sellers of existing homes raise their prices to take advantage of those higher prices. Even if it didn’t make housing more expensive, subsidized housing is not a solution to general affordability problems.

The latest technique is to demonize single-family zoning as somehow racist and to insist that such zoning be amended to allow more multifamily housing. However, single-family zoning can’t make housing more expensive so long as vacant land is available to build more housing.

The goal of abolishing single-family zoning is to replace some single-family homes with multifamily housing. This increases the housing supply but reduces the supply of single-family homes that most Americans want. Apartments and condominiums are not adequate substitutes for single-family homes, not to mention the fact that they are more expensive to build, so getting rid of single-family zoning only makes housing more expensive.

The truth is that opponents of single-family zoning don’t really care about housing affordability. Their goal is to increase urban densities. This is a nonsensical goal in a nation that is still more than 95 percent rural. Every state and every urban area in the country has plenty of land available for new housing if state or local governments would allow developers to use that land.

The war on sprawl has greatly harmed the American economy, increasing wealth inequality, creating hardships for low-income families, and exacerbating the homeless problem. It also played a major role in the 2008 financial crisis. It is time to end this war, including the war on single-family housing, and let people choose the kind of housing they want to live in, not be forced to live in the kind of housing some planners prefer.

public spaces, such as common hallways or greenspaces around developments, were a key factor in crime…..”

Then explain Europe and Asia. Public accessibility dud not hamper overall public safety. Porches, balconies and public spaces blend well.

Natural surveillance refers to the use of design and planning to create spaces that are easily viewed by residents, neighbours, and bystanders. This mechanism comes from the “eyes on the street” mechanism of Jane Jacobs. It is significant because offenders do not like any witnesses.

For centuries we used stigma and humiliation punishment to corral behavior to focus on social norms. What the modern political spectrum has done is pervert social norms…. thus behavior is seldom chastised. Shit on the sidewalk…. no biggie. Needles on playground…. who cares.

LadcyReader’s mention of Jane Jacobs sent me wandering the internet … and I found this interesting 20 year old Reason interview with Jane Jacobs …

City Views

Urban studies legend Jane Jacobs on gentrification, the New Urbanism, and her legacy.

https://reason.com/2001/06/01/city-views-2/

Reason: What do you think you’ll be remembered for most? You were the one who stood up to the federal bulldozers and the urban renewal people and said they were destroying the lifeblood of these cities. Is that what it will be?

Jacobs: No. If I were to be remembered as a really important thinker of the century, the most important thing I’ve contributed is my discussion of what makes economic expansion happen. This is something that has puzzled people always. I think I’ve figured out what it is.

Her answer? At the link …

”

No one would confuse subcompact cars for pickup trucks. Why, then, do people think that tearing down 2,200-square-foot single-family homes to make room for 1,100-square-foot apartments will make single-family homes more affordable? This is, in essence, what the movement to ban single-family zoning calls for. Clearly, many people supporting this movement fail to realize that, just as the market for subcompacts is completely different from the market for pickups, the market for multifamily housing is different from the market for single-family homes.

” ~anti-planner

On a similar note —

One has to wonder in places that start to allow for ADUs to be built, how many of them will be put into the short term rental ( AirBnB, Vrbo, et al ) market instead of the long term rental market.

These places are full of SFHs converted to a duplex, a basement studio, et al being used for short term rental. That’s competition for hotels, not housing prices. And because of that you may actually be _raising_ prices for the long term rentals, not lower them.

Here’s an example for airbnb vs long term rental.

Grand Forks isn’t a tourist town. Heck, it’s been somewhat untouched by the housing price increases. Yet the short term rentals can bring a month’s worth of rental revenue in all of 7 or 10 days.

https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/44611002?check_in=2022-06-15&check_out=2022-06-22&guests=1&adults=1&s=67&unique_share_id=1beb9ceb-c4b9-4883-8a53-41ed6e2c2062

https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/33191120?check_in=2022-06-15&check_out=2022-06-22&guests=1&adults=1&s=67&unique_share_id=5c9d63bc-4df8-48a5-9447-098ea4d47426

The other dimension of this is that inclusionary zoning much like UGBs and other restrictions is an obvious market constraint that favors investors and speculators. Its interesting to see how this has progressed. First you limit growth with a UGB which makes land speculation right outside of the UGB predictable and inflated. Once that occurs you use densification or “inclusionary zoning” to replace existing housing in the UGB that is already hooked up to utilities with more dense housing that people will be forced to buy for lack of reasonable alternatives. As a business strategy it makes sense. Granted it makes everyone else life miserable and does not contirbute to the greater economy.