Long before their title to the Willamette Valley and Cascade Mountain Wagon Road land grant was secure, the farmers and livestock owners who founded the company put the road and land up for sale. In 1871, they agreed to sell the company to someone named H.K.W. Clarke for just over $160,000 (about $4 million in today’s money), of which Clarke paid $20,000 and the rest was paid by someone named Alexander Weill.

This 36-page booklet was used to try to sell lands from the WV&CM land grant. Click image to download a 26.5-MB PDF of the booklet, which is from the Harvard Library.

This 36-page booklet was used to try to sell lands from the WV&CM land grant. Click image to download a 26.5-MB PDF of the booklet, which is from the Harvard Library.

At the time, the company had received title to just 107,893 acres, or about one-eighth of the final grant, but since the governor had certified the entire road by 1871, both sides were confident that the company would get the rest. While $160,000 for 860,000 acres of land is only 18-1/2¢ an acre, it is a pretty good return for the company owners who probably spent less than $30,000 building and maintaining the road and got most or all of it back in tolls.

Clarke and Weill were both residents of San Francisco and Weill was an agent for a Paris banking firm called Lazard-Freres. Weill never visited Oregon to view the road and lands and it is likely that Clarke never saw the road either. They were alerted to the opportunity to buy the company by railroader Thomas Edenton Hogg.

Hogg had built a rail line from Corvallis to Yaquina Bay parallel to (or on top of) the Yaquina Bay wagon road, and he wanted to extend it eastward along the route of the WV&CM road. After Clarke and Weill bought the company, Hogg was supposed to act as a local land sales agent, but instead he used the WV&CM lands as collateral to borrow money to build his railroad, which he didn’t have the right to do.

Hogg completed his railroad as far as Idanha, in the Cascade Mountains, and graded a route over Santiam Pass. To convince investors that he was successful, he had a few hundred feet of rails hauled up to the pass and built a make-shift box car so he could honestly say he had run freight over the pass. When Clarke and Weill sued Hogg for using their lands as collateral (which made selling land difficult as there was a lien against them), he disappeared for several years and it wasn’t until 1894 that they were able to clear up the title to the lands.

In the meantime, Clarke had died and his share of the company ended up in Weill’s hands, which meant it was entirely owned by the French bank. Sometime around 1890, Weill moved to Paris and a Charles Altschul became the person whose name was on the company deed, in other words, the local representative of the bank. He sold about 7,000 acres of land, but for the most part the bank seemed content to wait until land values increased.

Some people later charged that the company deliberately refused to sell any land hoping to drive land prices up, but this was unlikely. The reality was that much of the land had no value; it didn’t have any timber and didn’t see enough rainfall to support any crops. Most of the people who bought the 7,000 acres from Altschul ended up going broke trying to farm the land and were unable to make their mortgage payments.

Payday for the bank came in 1910 when St. Paul businessman Watson Davidson and a number of his associates agreed to buy the WV&CM company and the 794,000 acres of land that it still owned for $6 million, with $1 million down and the remainder to be paid over 6 years with interest. Davidson called his new enterprise the Oregon & Western Colonization Company.

The Great Northern Railway’s half subsidiary, Spokane, Portland & Seattle, was just completing a rail line to Bend that crossed the route of the wagon road west of Smith’s Rock. Not coincidentally, Davidson had a good friend, Louis Hill, Great Northern’s president, who was a silent partner in the Oregon & Western, owning 25 percent of the company.

Land sales didn’t go as quick as Davidson hoped and most of his other partners sold out their shares to Hill and Davidson. This left Hill owning half the company and Davidson most of the other half. For Hill, the cost of this land was a small share of his wealth and he could afford to wait for its value to increase. Davidson, however, had his fortune on the line, putting a strain on their relationship as he wanted to take actions to increase sales and Hill didn’t seem to care.

Finally, Davidson suggested to Hill that they divide the lands in two and Hill asked him to make a suggested division. In 1917, Davidson brought him a proposal that essentially used the Deschutes River as a dividing line. West of the divide was most of the timber, which hadn’t yet produced any revenue at all for the company. East of the river was most of the farm land, which had produced most of the revenue up to that point.

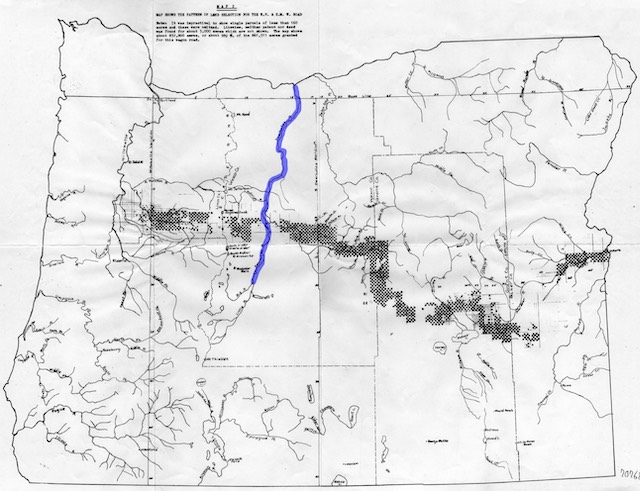

This map shows the WV&CM land grant as small squares with the Deschutes River, which became the dividing line between the Hill and Davidson shares of the lands, in blue. Click image for a larger view.

According to Cleon Clark, the former Forest Service official who wrote the history of the land grant, Hill “didn’t like the agricultural lands because this would mean a sales organization and the taking of mortgages that would drag on indefinitely.” But he also “didn’t like the timber lands because he couldn’t ethically develop them with his own railroads, the taxes were burdensome, and he was afraid of suffering large losses from fire.”

Clark doesn’t say where he got this information, but Louis Hill’s father, James, faced a similar ethical issue a few years before. Acting separately, James and Louis Hill spent a few million dollars buying 55,000 acres of mineral lands in northern Minnesota. It soon became clear that the iron ores on the land were worth far more than they paid for them. Hill the father didn’t think it was appropriate for him to profit from a transaction that he could have made for all the stockholders in the railroad. Further, federal laws discouraged if not forbade railroads from owning enterprises that ship things on the railroads.

Hill’s solution was to turn the lands into a trust and to give shares in the trust to Great Northern stockholders according to the amount of stock they owned. Over the next century, the trust cranked out $500 million in revenue to the stockholders. The Hills, of course, owned enough stock that they still got a good return on their investment, but the other stockholders benefitted as well.

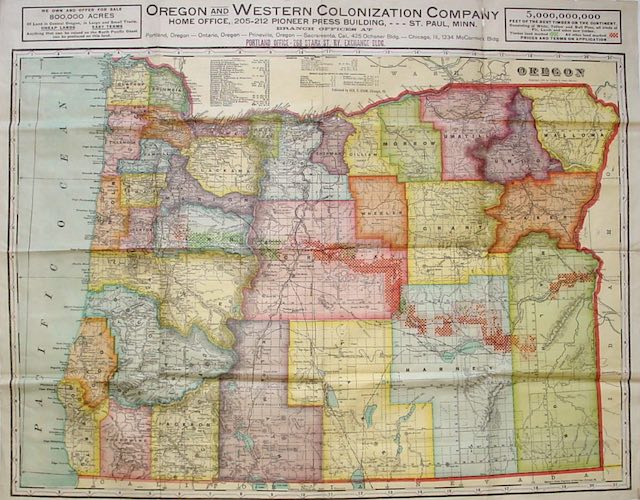

This map shows the WV&CM land grant as small squares. The green squares are timber lands and the red squares are farm or range lands. Click image for a larger view.

Louis ended up taking the western lands that had the smaller number of acres. In making this choice, I wonder if he realized something that Davidson might not have known about the timber. According to the Oregon & Western Colonization booklet shown above, the eastern half of the lands included 41,000 acres of timber land stocked with an estimate 320 million board feet of pine. The western half included 126,000 acres with about 650 million board feet of pine.

The western forests, however, also contained an estimated 4.9 billion board feet of what the prospectus describes as “fir.” True fir was considered a trash species. It isn’t as strong as pine, it isn’t as pretty as pine, and where pine wood gives off a wonderful odor, white fir in particular is known to loggers as “piss fir” because of its foul odor.

But the 4.9 billion board feet of timber in the western forests wasn’t really fir. Instead, it was Douglas-fir, a completely separate species in a completely separate genus. Structurally, Douglas-fir wood is actually stronger than pine. It isn’t quite as pretty as pine but it does have a nice odor. As of 1910, Oregon timber land owners hadn’t yet figured out how to market Douglas-fir, often selling it as “Oregon pine.”

Davidson probably didn’t know the true value of what he considered to be the smaller half of the land grant. For that matter, Louis Hill probably didn’t know either, but he was willing to wait until the market for timber became strong enough to provide him with a return.

The eastern lands continued to be sold by the Oregon & Western as buyers could be found. Farm lands went first, but the company had a difficult time interesting ranchers in the range lands that made up most of its holdings. It probably would have been forced to let the lands go for taxes as those ranchers felt free to run their livestock on federal lands. Davidson himself went bankrupt trying to keep the company going.

In 1934, however, Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act, which set up a system requiring ranchers to pay fair market value for grazing livestock on the federal lands. This boosted the value of the Oregon & Western lands, which sold nearly all of its remaining land by 1950. In the mid-1950s, the remaining assets of the Oregon & Western Colonization Company, which were mainly some mineral and water rights, were sold to a Washington man named Tony Fernandez. What is left of them are currently owned by his son, Daniel Fernandez.

I’ve really enjoyed the history of Oregon roads and rail in the past week.