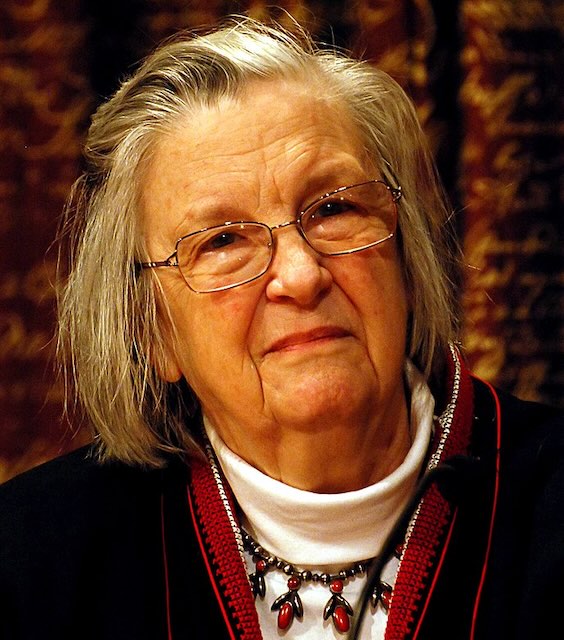

With President Biden handing out $6 billion for California high-speed rail projects and $2.2 billion more for other passenger-rail projects, it seems important to review some basic guidelines for infrastructure spending. Nobel-prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom, whose work focused on incentives and institutions, once offered the following evaluation criteria:

Elinor Ostrom. Photo by Holger Motzkau.

- Efficiency: How well are inputs translated into outputs?

- Fiscal equivalence – Do those who benefit from a system pay at a level

commensurate with their benefit? - Redistribution – Does the system take from the rich and give to the poor or from rich areas to poor areas or rich groups to poor groups?

- Accountability – Do decisions reflect the desires of final users and other stakeholders?

- Adaptability – Can infrastructure providers respond to ever-changing

Environments?

Alan Pisarski.

Transportation expert (and author of Commuting in America) Alan Pisarski has a more detailed set of guidelines.

- Who wins; who loses? Are we robbing Peter to pay Paul? Who is Peter? Who is Paul?

- What is the cost per person (or person-mile, or vehicle-mile) served? Does it pass the laugh test?

- What is the relationship between what the user pays and the total cost of this expenditure?

- Are we using actual realistic values or best-possible-situation estimates?

What is the track record of such cost estimates/ridership estimates by this

group and others in the past? - Is the public sector doing something the private sector should be doing? — or the converse?

- Is there a slippery slope here – leading to further needs and expenditures?

- Is this a nice-to-do expenditure that detracts from the ability to meet must-do needs?

- Can you trust the use of the word “efficiency”? The efficiency of whom or

what? Are users being penalized in order to make “the system” work better?

What share of available resources are being used to address what share of

our problem? - Are we planning to make a large segment of the population miserable enough

to get some of them to change their behavior? Is that rational in a pluralistic society? Would a technological solution do just as well or better?

Those are all good guidelines. But here are the guidelines that I suspect many transit and rail transportation planners actually use.

- Does the project cost enough money to generate political support from potential contractors?

- Does it spread the costs out to enough taxpayers that few will make an effort to complain?

- Does it look sleek and futuristic in a photograph even if it is slow and clunky in real life?

- Does the project have a low enough capacity that it will look crowded and successful even if few people use it?

- Are there enough low-income people around who might use it to justify regressive taxes to pay for it?

- Can we mention congestion in a description of the project even if the project will actually increase congestion?

- Does it relieve congestion or improve traffic flows? (If so, don’t build it because it will simply lead to more driving.)

- Will the project build an immovable piece of infrastructure that will justify more subsidies or major land-use changes to generate customers of the original project?