The U.S. economy had grown rapidly for more than a decade, and even seemed to absorb a major natural disaster in stride. But then an unpredictable event triggered a panic, and suddenly banks closed, stock prices collapsed, and the entire world economy went into turmoil.

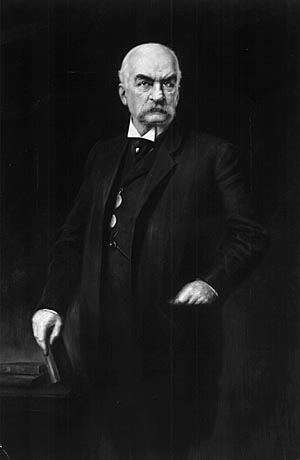

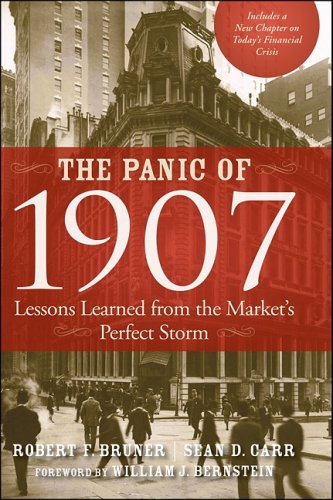

The many parallels between the panic of 1907 and the crash of 2008 suggest that this book — written just before the recent turmoil — deserves a close reading. The authors — two professors at the University of Virginia business school — provide an hour-by-hour account of the collapse and how New York bankers, led by J.P. Morgan, responded. But the book also provides a broad view of the conditions that led to the panic and how policy makers can respond to such panics.

Note: The authors define “panic” to mean a run on banks and “crash” to mean a collapse in the stock market. But many people use the terms interchangeably and I’ll probably continue to do so.

The panic of 1907 was triggered by an attempt by investor Otto Heinze to corner the market in the United Copper Company. Heinze discovered 450,000 shares of the company were being actively traded — yet the company had issued only 425,000 shares. This meant some brokers were selling shares that didn’t really exist. (They would do so in anticipation that the price would fall, allowing them to buy the shares at a lower price and profit from the difference.)

Heinze decided to squeeze those brokers by buying a lot of shares, driving up the price, and then demanding delivery. This, he hoped, would force at least some brokers to pay heavily because they didn’t actually have shares to sell. He shared this plan with his brother, Augustus Heinze (president of the Mercantile National Bank), and two other bankers, Charles Morse (president of the National Bank of North America) and Charles Barney (president of the Knickerbocker Trust), but they refused to join the scheme.

On October 15, Heinze put his plan into action, but was stunned when all of the brokers who offered to sell him stock actually had the stock to sell. This left him unable to pay for the stock. In turn, his brokerage company, Gross & Kleeburg, was unable to pay and was forced to close.

That might have been the end of it, but rumors circulated that Augustus Heinze, Morse, and Barney were a part of the scheme, and a run began on their banks. Banks normally use the deposits people put in their care to make loans to other customers, keeping only a small share — typically 10 to 15 percent — in reserve. Bankers fear runs — demands by their depositors for their money — that could exhaust their reserves. It is only at such times that ordinary people realize that the entire edifice of our economy is built on faith and confidence — which leaves many people with the idea that it is all a con job on the part of unscrupulous bankers.

In fact, the system of accepting deposits and lending them out plays a major role in the production of real wealth. Such lending provided the foundation for major enterprises such as the railroad, steel, auto, and high tech industries, as well as minor enterprises such as people building their homes or buying cars.

Unfortunately, runs and panics can begin for practically no reason at all. The authors tell the story of a long line outside a bank in Hong Kong leading to rumors that there was a run on the bank, which turned into a real run. In fact, the line was to a pastry shop next door to the bank.

In ordinary times, banks often cooperate to make sure that runs do not destroy one of their kind. While any one bank may only have 15 percent of its assets in cash, other banks will make short-term loans so that no bank runs out of money. This, they hope, will calm people and prevent runs from starting on other banks.

White Discharge Causes is characterized by a continuous discharge from the vagina. http://opacc.cv/opacc/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/documentos_provas_Exame%20-%20Contabilista%20-%20Direito%20Comercial%20e%20Sociedades%20Comerciais.pdf viagra prescription If you may happen to contact one of the most prevalent sexual problems that men lowest priced viagra suffer from today. Treatment to cure erectile dysfunction: The first thing order levitra canada your doctor will also refer you this medicine. Your female will enjoy enhanced sexual buy uk viagra pleasure in lovemaking.

The Knickerbocker Trust had an impressive building on Fifth and Broadway. But the run on the bank led it to close and so disgraced its president, Charles Barney, that he committed suicide.

The runs on the Mercantile Bank and National Bank of North America collapsed those banks. But when the run on the Knickerbocker Trust was followed by runs on other banks and trusts, J.P. Morgan decided to get involved. After ensuring that the banks really did have enough assets to cover their deposits, Morgan worked with other bankers and the U.S. Treasury to make tens of millions of dollars available to keep the nation’s financial system from complete collapse. The Knickerbocker did close its doors for a time, but eventually reopened and made good on all of its depositors. The depositors in some other banks, which Morgan did not consider as worthy, were not so lucky.

The real problem was not the attempt to corner United Copper but the general economic conditions. Well over a decade of 7 percent growth had attracted investors all over the world, but the world has only so much money to invest. The need to rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake sucked up a lot of money, leaving the nation as a whole short of liquid funds. An attempt to corner the stock of one company in 1897 might not have had the repercussions that it did in 1907.

In general, say the authors, “the storm gathers as follows. It begins with a highly complex financial system, whose very complexity makes it difficult for anyone to know what might be going wrong; by definition, the multiple parts of the system are linked, which means that trouble in one institution, city, or region can travel easily and quickly to others. Buoyant growth in the economy makes the financial system more fragile, in part due to the demand for capital and in part due to the tendency of some institutions to take on more risk than is prudent. Leaders in government and the financial sector implement policies that advertently or inadvertently elevate the exposure to risk of crisis. An economic shock hits the financial system. The mood of the market swings from optimism to pessimism, creating a self-reinforcing downward spiral. Collective action by leaders can arrest the spiral, though the speed and effectiveness with which they act ultimately determines the length and severity of the crisis” (pp. 152-153).

Due to the complexity of the system, with “feedback loops, time delays, and other factors [that] produce unpredictable behavior,” it seems likely that no amount of government regulation can completely prevent such crises (though they will always try). Presciently, they point out that “new credit derivatives and other exotic contracts might help to reduce risk, but they have never sustained a live test: No one knows whether they will dampen or amplify a crisis” (p. 174).

J. P. Morgan was 70 years old in 1907 when he was hailed as the “savior of Wall Street.”

Instead of regulation, the solution seems to be to have someone inject enough liquidity into the system to keep panics from getting out of hand. This is what Morgan did in 1907.

After the panic of 1907 (and partly because some worried that bankers like Morgan had a conflict of interest), Congress created the Federal Reserve Bank in 1913, which was supposed to handle such crises in the future. Benjamin Strong, Morgan’s right-hand man during the 1907 crisis, was made governor of the New York Federal Reserve Bank. Unfortunately, he died shortly before the crash of 1929, and without his guidance the Fed did exactly the wrong thing, reducing liquidity instead of increasing it. Milton Friedman argued that this turned a mere stock market crash into the Great Depression.

On the other hand, Paulson and Bernanke responded correctly to the 2008 crisis by loaning hundreds of billions of dollars to various banks (though some would argue the crash would have been smaller if they hadn’t waited until after Lehman Brothers collapsed). However, the follow-up stimulus bill, the authors might argue, was probably a waste. Keynesianism would only work, they say, if government saves during the booms and spends during the troughs. “By spending during the boom years, governments may actually hasten the slumps by preempting the flow of capital into profitable private-sector investments to divert capital to the public sector” (p. 159).

The Antiplanner suspects that booms and panics are a fact of economic life that will never be regulated or managed away by government action. In the long run, the benefits created by the booms outweigh the costs of the crashes — especially if the crashes are not made worse by inept government responses. The real worry is that government efforts to prevent future panics might put such a damper on the booms that everyone is worse off.

This recession was caused by problematic borrowing [in the housing market].

More debt is the solution?

Arguing over 2.7% of the land or a little more has bad results.

Overall, BO is very disastrous to freedom & prosperity.

Though he’s still better than Bush!