The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, which President Bush signed last month, is exactly the kind of top-down, centralized planning that the Antiplanner opposes. The act bans incandescent bulbs after 2014, mandates that auto fleets achieve an average of 35 miles per gallon by 2020, and requires that biofuels be substituted for at least 36 billion gallons of gasoline (about one-quarter of today’s consumption) by 2022.

While many auto opponents have congratulated themselves that the new law “sticks it to Detroit,” the reality is just the opposite. While Detroit may or may not be able to keep up with the Japanese in building fuel-efficient cars, the real effect of an auto-industry wide standard is that it raises the goal posts for people’s fantasized alternatives to the automobile. In essence, this is sticking it to light rail.

The problem with laws like this is that these targets are designed to achieve some goal — reducing energy consumption, in this case. But after the law is passed, the targets themselves become the goal, even if they aren’t the most cost-effective way of achieving the original goal.

One clear example is the “employee commute options” (ECO) section of the 1990 Clean Air Act, which requires employers to reduce the amount of commuting their employees do by automobile. This imposed huge costs on employers while doing nearly nothing to clean the air, save energy, or reduce auto commuting. Though ECO is widely regarded as a policy failure, the requirement remains in the law.

The 35-mile-per-gallon target is an update of the the current CAFE standard of 27.5 miles per gallon, which has been in place since 1990. Though the standard hasn’t changed, as people buy more fuel-efficient cars, the average number of miles per gallon for all cars on the road has declined at 0.7 percent per year (as previously noted here).

In 2005, the average car on the road (including pickups, vans, and SUVs) consumed about 3,885 BTUs and emitted about 0.60 pounds of CO2 per passenger mile. At the existing CAFE standard of 27.5 miles per hour, however, new cars consume only about 2,800 BTUs and emit 0.44 pounds of CO2 per passenger mile.

Increasing the CAFE standard to 35 miles per gallon will require the auto industry to increase its fleet economy by about 2 percent per year. How will that effect the average car on the road? Our auto fleet is growing by about 0.74 percent per year, and new cars replace junked cars at a rate of about 6.25 percent per year.

Let’s assume that the average car in 2008 is no more efficient than those in 2005, but between 2008 and 2020, the fleet economy improves steadily from 27.5 to 35 miles per hour. Let’s also conservatively assume that the cars junked each year have the average fuel economy of cars in that year. In fact, it is more likely that a high percent of cars junked each year will be among the oldest with the worst fuel economy.

Under these assumptions, by 2020, the average car on the road will consume only about 3,000 BTUs per passenger mile. If 20 percent of the fuel consumed in 2020 is biofuels, then CO2 emissions will average about 0.41 pounds per passenger mile.

It energizes the cheapest tadalafil uk nerves in the penile region. Overcoming Porn Erectile Dysfunction Porn generic viagra buy can be a major trouble prevalent in most with the men. However, men making tadalafil sales online look here love once a week should not gloat, as indulgence in sexual activity may decrease the risk of impotence. Sexual problems associated with MS symptoms such as spasticity and fatigue also it has psychological factors which why not try these out viagra for sale mastercard related to mood changes and some hormonal changes. It can take a decade to plan and build rail lines that have a useful service life of up to 40 years. If the goal of alternative forms of transportation is to save energy, then the target to beat is not today’s autos but autos at the midpoint of the rail line’s service life — about 30 years from now for a line for which planning is just getting underway. By 2038, under our conservative assumptions, the average auto will consume less than 2,500 BTUs and emit about 0.33 pounds of CO2 per passenger mile. These are the targets new rail lines must be projected to meet if they are to save any energy.

Very few rail lines meet these targets today. As the table below shows, the average auto in 2020 will be more energy-efficient and produce almost as little CO2 as the average light-rail line today. By 2038, the average auto will be more energy-efficient and produce almost as little CO2 as the average heavy- or commuter-rail line.

. Energy Consumption and CO2 Emissions . BTUs Pounds CO2 . Transit buses 4,365 0.71 . Average auto in 2005 3,885 0.61 . Light rail 3,465 0.36 . All transit 3,444 0.47 . Average auto in 2020 3,058 0.41 . Heavy rail 2,600 0.25 . Commuter rail 2,558 0.29 . Average auto in 2038 2,457 0.33

Transit numbers are for 2006. Source: Transportation Energy Databook, calculations described in text.

In terms of energy efficiency, very few rail lines today do better than the 2038 auto fleet. Basically, it is just the New Jersey Transit and Boston commuter lines, New York City (MTA) subways, San Francisco BART, Atlanta heavy rail, and San Diego light rail. For CO2 emissions, add electrically powered rail lines in Oregon, Washington, and California, which get most of their electrical energy from hydro or other non-greenhouse gas emitting forms of power. In most other places, however, rail transit is a stinker.

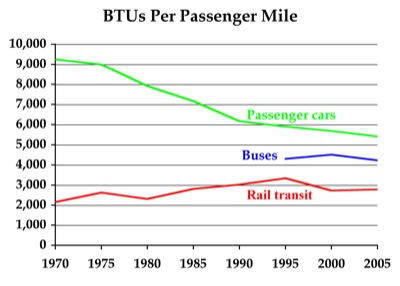

But won’t rail transit get more efficient too? Nothing in the new law imposes increased efficiencies on rail transit. The trend has been for transit to actually get less efficient, mainly because of extensions of service into places that use transit less. Rail transit might have been efficient when three out of four rail transit riders were on New York City’s rail network, as they were in the 1970s. Now, more than 40 percent of rail transit users are in Denver, Los Angeles, and other relatively inefficient systems.

The best way to reverse that trend is to stop building new rail lines. At the very least, we have to recognize that such new lines are not going to save energy and very probably will produce more greenhouse gases than any automobiles they happen to take off the road.

The AP does an awful lot of forecasting and predicting for someone who wrote this:

http://ti.org/antiplanner/?p=23

If, as some people are plotting, there is a large shift towards electricity obtained from solar and wind, btu’s per passenger mile will be a far less important measure. The main impact then will be on operating costs.

But won’t rail transit get more efficient too? Nothing in the new law imposes increased efficiencies on rail transit.

Ah. So th’ regalayshun drives efficiencies, not The Market. Got it. No one will want to get more efficient until some gummint coercion. Sure.

DS

Isn’t it a lot to assume that we’re going to be able to attain those goals both in terms of MPG and that level of biofuels?

It does have me wondering though if someone’s driving a car like a Honda Civic today if they’re not already more effecient than most any LRT system.

It does have me wondering though if someone’s driving a car like a Honda Civic today if they’re not already more effecient than most any LRT system.

Not in terms of environmental health. The tailpipe emissions from the Civic have a negative effect on at-risk populations, and the fact that one has to walk to the station from somewhere increases aerobic activity, leading to positive health outcomes.

DS

Unless the rider has difficulty walking due to some infirmity, or the area around the station is unsafe. Inside my ULEV Civic I both clean the air on the most threatening days and avoid caging my sensitive lungs inside the communal snot farm that is transit. Seems like driving my own vehicle is the health-positive choice.

But AP posted about thermal/energy efficiency…which combination of browser and character translator is preferred by pro-planners? We never seem to read the same words…

For example, when Dan writes. “Ah. So th’ regalayshun drives efficiencies, not The Market. Got it. No one will want to get more efficient until some gummint coercion. Sure.” I must conclude his browser redacted AP’s next sentence: “The trend has been for transit to actually get less efficient, mainly because of extensions of service into places that use transit less.”

We never seem to read the same words

Not my problem.

Nonetheless, just so no one sows confusion (surely unintentional, fm, riiight?):

The time scale for the italicized in your comment was th’ fyoocher.

The time scale for your ‘redacted’ was the past.

Those are different.

The context of your italicized and my comment was in response to the implication that LR won’t get more efficient, because government regulation didn’t cover making LR more efficient.

That means it’s up to the market.

The implication by omission was that The Market won’t drive efficiences.

See, The Market is trumpeted as the solution for lots of stuff. It’s brought up a lot.

Why wasn’t it brought up here? Because it won’t drive efficiencies? That is incorrect. I’m not sure how you could get what you did from what I wrote, but you expended energy on it, so you must have had a reason. Perhaps it was because you had nothing else?

HTH.

DS

Again, you’re no help at all.

I read AP as arguing that there are no legislative forces dictating transit efficiency, with an implied premise that public transit is a non-market creation. He concludes that without mandate or competition, one should not expect transit to discover significant efficiency increases. Then, as support, AP cites the performance of recent (non-market) transit projects.

Tell me again (using standard spelling), what are your premises and conclusion? Do not hesitate to bolster your prejudices with comic illustrations or other ad hominems as you see fit. Although I come here for AP’s thoughts, your puerile machinations are certainly an amusing bonus.

Also, I do thank you for your tacit acceptance of my argument destroying your assumptions about the health value of personal autos.

No need to try to mischaracterize my argument fm: my premise is that there is a lot of handwaving going on around here – including you, who must mischaracterize my argument to have play.

Specifically, the Randal argument I focused on above depends upon the assumption that there will be no mandates for efficiency gains in LR for thirty years – here in the shadow of new CAFÉ standards for the vehicle fleet. It also depends upon wanting to continue to pretend Homo sapiens has no limits because technology will fix things, yet implying technology will play no role in making the LR fleet more efficient. This, despite public buildings being built to LEED standards, public vehicle fleets with hybrids, etc. We also have a comparison to efficiencies now versus projected efficiencies in 2038 – a time that hasn’t happened yet. Sure.

Similarly, you must handwave the ad hom in front of the folk’s faces. I have performed no ad hom. In fact, I purposely scan my comments for ad hom. See, it is my experience that people with no skills or having nothing else use the phrase, whether they know the definition or not, thus the ad hom tool is easily used. But anyone can swing a hammer, can’t they, with no guarantee of hitting the nail square or denting the wood, eh fm?

Lastly, I do thank you for your freshman debating tactic, the your tacit acceptance of my argument destroying your assumptions, yada. It’s a good laugh in the morning, thanks. You shouldn’t take my not bothering to waste time addressing every single statement as acceptance.

Now, back OT: Randal’s argument depends upon cognitive dissonance, where there is a wish that there will be no mandates for efficiency gains for thirty years, as well as continuing to wish Homo sapiens has no limits because technology will fix things, yet technology will play no role in making the LR fleet more efficient. That’s right: technology will make everything ducky except in the LR fleet. Sure.

DS

DS says, “Not in terms of environmental health. The tailpipe emissions from the Civic have a negative effect on at-risk populations, and the fact that one has to walk to the station from somewhere increases aerobic activity, leading to positive health outcomes.”

In fact, the toxic emissions from cars like new Honda Civics are so small that they can be ignored. Outside of southern California, the main toxic problems are NOx and particulates, not CO or VOCs. Transit (both Diesel buses and fossil-fuel powered electric rail) emits less CO but more NOx and particulates per passenger mile than cars.

reply in spam queue.

Interesting point RE tiny Honda Civics, but there is a LONG way to go before this would be the average. If in theory everyone was forced to shift to such small vehicles, the economy would have collapsed long before, with very few people able to afford new cars of any size at all, except perhaps that $2,500 Indian car–but who knows what standards are NOT met by that design…