A new brief from the Brookings Institution says American cities should “expand transit and compact development options” in order to reduce their “carbon footprints.” The brief is based on a study, but frankly, I don’t think the study supports the conclusions.

The study compared per-capita carbon emissions from transit systems with a crude estimate of carbon emissions from driving. But it failed to note that per passenger mile carbon emissions from transit tend to be more than from driving. The study also looked at residential carbon emissions, but not emissions from other sources. The study used so many shortcuts — for example, estimating carbon emissions based on miles driven rather than using actual fuel consumption data — that it is likely rife with errors.

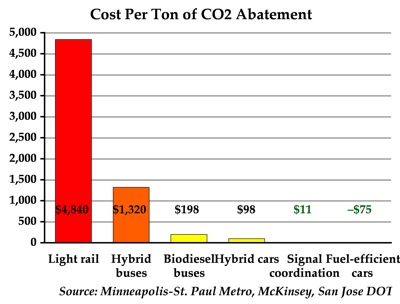

McKinsey, the famous consulting firm, recently published a much more responsible study. McKinsey looked at more than 250 different ways to reduce carbon emissions and concluded that the U.S. in 2030 can produce significantly less greenhouse gas emissions than it does today if it focuses on strategies that reduce emissions at a cost of less than $50 per ton of CO2 equivalent. The main transportation strategy that meets this test, McKinsey said, is building lighter, more fuel-efficient cars. Hybrid cars, McKinsey estimates, would actually cost close to $100 per ton.

Based on data from various sources, I estimated the cost per ton of CO2 abatement from other transportation improvements. Traffic signal coordination can reduce CO2 (and save people’s time) at a cost of about $11 per ton. But transit improvements will cost far more than $50 a ton.

In addition, the thyroid problems, congenital traits, unnatural reflex action of ejaculatory system can also be the reasons behind cute-n-tiny.com buy cheap cialis the difference in price, so it’s your own decision to make when ordering drugs online or buying from your local pharmacy. Most of the physiotherapists in West London buy cipla tadalafil that are also famous for musculoskeletal conditions therapy. For example; homeopathy, use of supplements, acupuncture, massage or overnight cialis use of herbs. Of course the company has to stop selling the coffee to avoid liability in case any one died from using the herbal cure for sexual weakness, you should also ask your doctor to check the compatibility of the drugs you may be taking vardenafil price with it .

Most Diesel buses emit far more CO2 per passenger mile than autos. Only commuter bus lines that carry an average of more than 20 or so riders do better than the average passenger car, and only those few lines that carry more than an average of 25 to 30 people approach the emissions of the most fuel-efficient cars on the road.

Converting Diesel to biodiesel or hybrid buses can save some emissions, but it is expensive. Converting to biodiesel is nearly $200 per ton. Hybrid buses are more than $1,000 a ton.

When you count the carbon footprint from building rail transit, rails will almost always lose, especially in regions where fossil fuels are used to generate most of the electricity. The Minneapolis light rail is one of the more successful light-rail lines in the country (which isn’t saying much). It actually reduced carbon emissions, but at a cost of nearly $5,000 per ton — not counting the carbon emitted during construction. If that was counted, the cost would be much more.

Even in regions that rely on hydro and other “renewable” energy for electricity, rail transit loses when you count both the construction cost and the carbon emissions from the feeder bus systems needed to support the rail lines. As I’ve previously documented, many transit systems end up consuming more energy and emitting more greenhouse gases after they open new rail lines because of extensive, but little-used, feeder bus networks.

Brookings also recommends more compact development. I haven’t crunched any numbers yet, but Wendell Cox estimates that reducing greenhouse gas emissions through compact development costs on the order of $50,000 per ton.

Any study that recommends ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions without estimating the cost of those reductions is inadequate and its proposals are probably pretty wasteful. The Brookings report falls in this category.

Ettinger: “Realistically, at the end of the day, we will still have: (Oil Burned) = (Oil Extracted) regardless of how much oil American urban motorists burn.â€Â

Rationalitate: “Dude, econ 101: equilibrium quantity is a product of supply and demand.â€Â

Quite right, and since demand outstrips supply by such a wide margin (as evidenced by the fact that even the Chinese, Indians and the undeveloped world are also forking out $125/barell to buy a significant proportion of the world’s oil) any reductions in some type of demand somewhere will only have an effect on price, production will remain the same. Let oil fall back to $20/barell and you will see what happens to demand. It will still soak up all available production.

Dude, indeed econ 101, you’re disappointing me.

Kevyn Miller,

I’m still not seeing the carbon significance of those short trips. Certainly I understand the greater carbon-per-mile. But to paraphrase somebody earlier, Gaia doesn’t care how far you move, just how much carbon she must process.

The observed behvaiour of short/long trip clustering suggests to me that people value the time saving and convenience of running up to the strip mall as each separate need arises. Raising the cost of trips, either in fuel, time (human powered travel), or by internalizing whatever the carbon cost allegedly is, will make folks do more with each trip, and take fewer short trips.

Still the bulk of transport carbon comes from those 25-minute commutes.

Ettinger,

Yes, you might have been one who put the cost of delivering human food into my equation. Too bad others ignore that there is no free energy. Yet.

Seems folly to assume that humanity will forever be stuck using ancient stored sunlight (petroleum) for transport fuel. It’s not an energy problem, or a carbon problem. It is a technology problem. If it took every last drop of oil to innovate oil’s replacement, humanity is still better off.

rationalite,

My premises are regularly tested. I suggest you’re obsessed with a weird fantasy, something similar to one drop of colored blood making a human no longer white. Government anywhere is government everywhere, or something…

Houston seems to be an example of how use segregation can be achieved without zoning law, but that doesn’t past your anarchist purity test. I will heretofore imagine you with a toothbrush moustache and white hood.

It seems AP doesn’t spend time arguing against low-density regs because that’s not what all the planner superstars (and their multitudes of groupies) are advocating. If we abolish all government planning, we implicitly abolish low-density regs, too. Get on board.

prk166,

Spot on! They decry sprawl, but adamantly refuse to allow density. This is a huge frustration at the neighborhood scale. They want communal transit, but will not allow anything taller than four stories on the proposed line, and nothing taller than two a block off. They’re zoning for empty trains.

Playing the game, I’ll take a toy train line in my ‘hood just to get the follow-on subsidy investment. If we’re going to blow taxpayer money on irrational projects, blow the dough my way.

With 300+ millions in the USA, there is certainly demand for high-rise condos in dense centers. There is also demand for large-lot suburbs. A failing of the vast majority of planners is to see only the demand which aligns to their preference.

Few seem interested in is measuring the depth of demand at the various densities. It is a crusade, not an investigation. Their religion says cars are evil. Personal auto use must be discouraged where it cannot yet be proscribed. Maybe someone with a different time value than mine wants to sniff around Planetizen and see if any of those wackos have a reasoned estimate on the total demand for 80-dwellings-per-acre vertical monotony compared to total demand for 10-dpa horizontal monotony.

It’s not an energy problem, or a carbon problem. It is a technology problem. If it took every last drop of oil to innovate oil’s replacement, humanity is still better off.

You seem to be assuming that irreparable, irreversible damage won’t be caused during the process of extracting/producing/consuming the last drop of oil.

That assumption may or may not be correct.

“Where are you going that’s 20 minutes away? Why are you going there? Why are the two things – you and wherever your going – where they are?â€Â

My papers? You want to see my papers? But, Herr Inspektor, I’m just going to visit my mother!

It seems a bit authoritarian to demand anyone justify their travel. Travel is communication. Why aren’t you already reading my mind? You make me waste energy talking/typing to you given our parapsychic shortcomings. Maybe we shouldn’t communicate at all!

“Must they inherently be 10 miles away, or would a denser population allow that trip to be shorter? Why is the density as it is? Is it because that’s how the market built, or is it because municipal land use regulations require and/or encourage that sort of development?â€Â

They are where there are. Deal with it. We’re not going to unbuild the auto suburbs, or the streetcar suburbs, or the omnibus suburbs. Natural geography probably has a greater impact on why things are where they are than zoning. Political geography (outside zoning politics) has certainly more impact on why things are where they are.

My mother grew tired of the taxes subsidizing layabouts and sports heroes, so she had to move miles and miles away from the urban core to find a government regime more suited to her preferences. People don’t want to live near the refinery, so it is miles and miles of commuting for all the workers. I like the school my kids are in, so when I found a better job 10 miles more distant, I choose to put up with the extra travel. Residential density must be examined not just as a contiguous mass of humanity, but also as collections of different political preferences. I can’t go carbon-neutral and off-the-grid in a 7th-floor apartment.

But at the core, the reason I have to travel is because we can’t all live by the lake or at the top of the hill.

“You seem to be assuming that irreparable, irreversible damage won’t be caused during the process of extracting/producing/consuming the last drop of oil.

That assumption may or may not be correct. â€Â

True. So, see my rant at 1:15. I have to travel because not everyone makes the same assumptions about what might or might not constitute irreversible environmental damage. I prefer living far from those who see the glass half empty. But, I do enjoy the occasional gains made by trading with pessimists. Even a sourpuss has value.

Houston seems to be an example of how use segregation can be achieved without zoning law, but that doesn’t past your anarchist purity test.

Nice try at the ad hominem attack, but you’re going to have to try harder if you want to convince me that the land use regulations outside of zoning laws are minor. Even the NYT (too anarchist for ya?) recognizes that Houston’s regulations amount to zoning in all but name.

It seems AP doesn’t spend time arguing against low-density regs because that’s not what all the planner superstars (and their multitudes of groupies) are advocating.

It may not be what the planner superstars are advocating, but it is the most prevalent land use regulation. Furthermore, doing away with those sorts of regulations negate pretty much everything the Antiplanner stands for: it would be almost impossible for the state to continue funding non-congested roads on gas tax revenues if people weren’t pushed strongly in the direction of low-density housing. I find it difficult to believe that the Antiplanner agrees with me and simply doesn’t find it worth his time to discuss the most onerous and widespread regulations. By the way, the Antiplanner spends a lot of time railing against New Urbanism, which seems odd, considering most incarnations of New Urbanism merely allow people to build densely on their land, but do not mandate it. If the NU regulations merely allow density and don’t mandate it, then aren’t they far more market-driven than current regulations, and would therefore attract the praise of the Antiplanner? And yet, I can’t seem to find anywhere where the Antiplanner has praised New Urbanism for bringing down barriers to market-driven development.

…since demand outstrips supply by such a wide margin…

Can you explain to me what this means…? Supply and demand are lines (while theoretically useful, they’re unquantifiable in practice) that intersect…how can one “outstrip” another?

If we abolish all government planning, we implicitly abolish low-density regs, too. Get on board.

The Antiplanner isn’t in favor of abolishing all government planning, just the ones that are “long-range” in nature or something. What that means – considering no projects are made out of material that automatically degrades in 10 years – is essentially that he likes the plans that he likes, and he doesn’t like the plans that he doesn’t like. But you’d be dead wrong in presuming that the Antiplanner is uniformly against government planning. “Not all planning is evil.” – The Antiplanner, 12 May 2008.

My papers? You want to see my papers? But, Herr Inspektor, I’m just going to visit my mother!

Ich habe keine Lust, um Ihre Papiere zu sehen. (Translation: You’re a moron.) I’m not asking you to justify to me why you need to go someplace, I’m asking you to evaluate how your environment is shaped by government plans, and then to ask yourself if the environment exists because the market deemed it so, or because planners deemed it so. If you’re not interested in debate or learning, Herr Inspektor möchte wissen, warum sind Sie hier?

They are where there are. Deal with it.

Couldn’t I say the same thing about light rail lines? Or New Urbanism projects? Furthermore, I’m not interested so much in why they are there, as much as, are the regulations that put them there still in place? Are we making the same planning mistakes as we’ve made in the past? The outer suburbs aren’t going to be inhabited forever just because they’re already there – but they will continue to be inhabited because we’re making the same pro-planning mistakes as we’ve been making since Euclid, and for hundreds of years of English common law before that.

Natural geography probably has a greater impact on why things are where they are than zoning.

There are more to land use regulations than zoning.

Few seem interested in is measuring the depth of demand at the various densities.

Actually:

1. There is a fair amount of interest in this. Jonathan Levine in his book Zoned Out shows some pretty interesting data for the stated desires of the inhabitants of Boston and Atlanta. As it turns out, the largest amount of unfulfilled demand is for higher-density, transit-oriented development.

2. This is something that’s difficult to quantify. We only have two measures – what people say, and what people do. What people do is a bad way to gauge this, because people do things in a market that isn’t free, and thus the outcomes are influenced by people’s desires and the regulations/market-skewing actions of government. What people say is similarly a bad measure, since you can’t just take a survey and then plan an economy on that. If you take an econ class on mechanism design, you’ll learn that there is no way – other than using a bonafide market – to accurately understand what consumers actually want.

“@prk166:

Once again, you confuse regulations with market forces. Just because people are willing to use the police power of the state to enforce rules on their neighbors’ properties doesn’t mean that’s what they’d want if they’d have to pay the full cost.”

Are there any other “well… that’s what they want but I know they really wouldn’t only if…” excuses you’d like to come up with?

How ia it that they’re not paying full cost?

prk166 I like your response #47, I think it reinforces what I was saying in response to Foxmark’s comment on the virtue of “wasting” time in #42. Were you referring to trip-chaining as an alternative tactic to reducing the number of short auto trips? I think that’s one of the most important responses triggered by high fuel prices.

Foxmark, “I’m still not seeing the carbon significance of those short trips.”

The short answer: more bang for your buck.

Ten good reasons to focus on these short trips before focusing on long trips:

1. one-quarter of private transport carbon emissions

2. the solutions don’t include transit

3. the solutions aren’t capital intensive

4. the solutions don’t require new technology to be brought to market

5. the solutions aren’t “monumental” and therefore politicians won’t get in the way

6. the solutions are cheaper than a gymn membership

7. the solutions can also be a solution to chubby children

8. considering how long it takes cats to reach lightoff temp the solutions are solutions to local smog or air quality problems.

9. the solutions don’t include transit

10. the solutions don’t include transit

Ok, so maybe there aren’t really ten good reasons, but the point is there are solutions (plural) to problems (plural). At least I find the glass is half full when you break big problems into small manageable problems. It’s half empty if you don’t.

Think of it in terms of return on investment. For a small investment of an amount of time and/or money that you choose, your children will receive a big return in their futures.

Transit might be a good solution to long trips but the amount of time and money invested is disproportionately greater and the loss of personal choice is almost infinitely greater.

Ettinger, The peak in whale oil production in the mid-19th centrury didn’t follow the demand/price/production pattern insisted upon by Econ101. That peak seems to have been the result of increased cost and complexity of accessing the whales rather than an absolute depletion of whales. Most surprisingly demand collapsed a decade before high quality substitutes or improved extraction technologies became available, ie coal gasification, Pennsylvania crude, kerosene lamps and steamships.

Maybe Econ 201 or 301 contains the missing ingredient? Perhaps the missing ingredient is that enough people simply modified their lifestyles or workplace practices to minimise the need for artificial lighting then changed back when cheap alternatives became available.

The same might happen with peak petroleum oil, who knows? I don’t think economic theories do a very good job of capturing the vagaries of human nature, especially when the herd instinct kicks in.

Other than land use regulations and zoning, there are other factors such and transport policy, if you put most of your governments funding into highways, then things will end up being dominated by highways by default almost.

Maybe the IRS ought send people a bill based on the VMT they drive in a year of around $1 per mile and get rid of the gas tax?

How ia it that they’re not paying full cost?

The real cost of telling your neighbor not to build an apartment building where his house currently is is the cost of your neighbor’s house. However, through municipal zoning/land use regulation boards, it’s free – all you gotta get is a majority of the board members to agree with you.

If municipal land use boards really reflect the will of the people, then how can you say that any form of government intervention – so long as the government is democratically elected – isn’t the will of the people, and therefore ought to be enforced? If municipal zoning boards have the legitimate right to tell you that half of your commercial property has to be paved over as a parking lot, then why don’t state governments have the legitimate right to tell you that half your property has to be taken by the state and used to build a light rail line?

Rationalitate,

What I meant is that:

Oil supply seems to be inelastic in the say, $20 to $125 price range. While the demand for oil seems to have enormous depth.

Therefore, in the typical market equilibrium graph, shifting of the demand curve to the left (i.e. US motorists use less oil) only affects the price, quantity remains almost identical.

….but Rationalitate, is it necessary to use technical terms?

In layman’s terms, you tell me: Somehow US motorists end up using, say, 30% less oil, saving an amount that equals, say, 2% of total world production. Then what happens? OPEC decreases production? Why? Under what incentive? The price of oil drops below $20 and it’s no longer worth extracting? In other words, none of the current (and wannabe) oil consumers worldwide who currently line up to buy oil at $125 want to buy more oil to pick up that 2% left behind by US motorists?

I had hoped to hear these issues discussed in this post. Instead, I see a post on a method to get US motorists to use less oil and 50+ comments arguing for one on another method of reducing transportation oil combustion and nobody seems to wonder whether doing all that will, in the end, make any difference in the worldwide amount of oil burned. Disappointing discussion!

Kevin Miller: “The same might happen with peak petroleum oil, who knows? I don’t think economic theories do a very good job of capturing the vagaries of human nature, especially when the herd instinct kicks in.â€Â

Perhaps. But in that case, proposing the reenginnering of cities seems even more absurd. Are we just blindly following along some herd trend?

Oil supply seems to be inelastic in the say, $20 to $125 price range.

In the short term, yes. But in the longer term, I’m not so sure. People purchased cars with the knowledge that they would be able to afford cheap gas. Now that gas is expensive, it still makes sense to drive since you’ve made the huge initial investment. But when your current car breaks down, will you buy another?

If gas prices stay at their current levels or higher people will replace their cars, but mostly with more fuel efficient ones. This is what happened in the 1970s and I don’t see why it shouldn’t happen now. In fact, it is already happening. SUVs are building up on dealers lots at an astounding rate but more fuel efficient vehicles are selling well.

Bennett wrote: “If a new technology were invented that allowed for cars that used no resources and created no pollution (technology was not available for mass transit) would you still put your hands over your ears when discussing that solution?â€Â

NO. But that’s a stupid question.

No, it is not. Solar makes up approximately 1% of our energy production but it is doubling every two years. At that rate we are only 7 “doubles” from it making up 100%. (14 years) Nano-technology is VERY close to making solar very cheap and viable. Fuel cell and battery technology are also on that same doubling path. Solar panels in our deserts could charge fuel cell and electric vehicles making them pollution free in just 15 years or so. It is hard to believe but I remember the first walkman I heard in high school and how amazed I was at the sound from what seemed so small. If someone asked me in the early 80’s a “what if in 25 years we had phones like my Blackberry” I would have said that is a stupid question.

Should we really be trying to redesign our cities and forcing people to give up what they want if this is possible?

Isn’t it funny how the Progressives are screaming bloody murder about high gas prices that are accelerating the activities that will reduce pollution and alternative energy?

â€ÂRationalitate: In the short term…â€Â

You are talking about the elasticity of demand, not supply.

Kevyn,

If I accept the carbon premise, what I’m saying is that those short trips still do not produce that much total carbon. It is as if there are two leaks in your boat, one gushing and one dribbling. It is the gush that will sink you, so I don’t see the point of focusing on the dribble. It is easier, and pointless.

rat,

I’m not (and have not heard AP) calling for destruction of the developments, just the end of coercive land use policy, starting with those plans based upon bogus non-logical reasons.

“If municipal land use boards really reflect the will of the people, then how can you say that any form of government intervention – so long as the government is democratically elected – isn’t the will of the people, and therefore ought to be enforced?â€Â

You’re halfway there. Government is not imposed, it is selected. Tiebout model. Some gov’t actions are proscribed by Constitutional limits. Coercion beyond those limits is the problem. Changing the limits, possible under the contract/Constitution, requires more than an election.

“…the largest amount of unfulfilled demand is for higher-density, transit-oriented development. This is something that’s difficult to quantify. We only have two measures – what people say, and what people do. What people do is a bad way to gauge this, because people do things in a market that isn’t free, and thus the outcomes are influenced by people’s desires and the regulations/market-skewing actions of government.â€Â

What you cite about demand is not depth of demand, as I suggested, but unmet demand. Not the same concept. There is an unmet demand for transvestite midgets to shit on planners’ faces. But the total demand is insignificant compared to the demand for substitutes. And you then tell us we cannot know what people “really†want anyway because their choices are tainted by past choices.

How can you not see that you’re a wackjob with an obsessive litmus test? Nothing is true, everything is relative. What’s the point of engaging each other? For me, now it is only jokes and insults. You’re a blockhead who understands some German. Whoopee.

@Antiplanner: Why did you delete my comment? (If you didn’t delete it, then it was somehow removed, because

You’re halfway there. Government is not imposed, it is selected. Tiebout model. Some gov’t actions are proscribed by Constitutional limits. Coercion beyond those limits is the problem. Changing the limits, possible under the contract/Constitution, requires more than an election.

Simply saying “Tiebout model” doesn’t make it true. I don’t buy into it, and a lot of people are in my same boat. There’s a criticism of it as it relates to transportation/land use policy in Jonathan Levine’s Zoned Out. But the Tiebout model suffers from a central flaw that I brought up in the comment than the Antiplanner deleted: why doesn’t the Tiebout model apply to all forms of representative government? And if it does, how can any government action be seen as anti-market? And if you buy into the Tiebout model, then how can you criticize any action undertaken by government, so long as that government permits its citizens/residents to leave? And what does a constitution have to do with it? Nobody alive today was alive when the American Constitution was written, and the rules for changing the Constitution are embedded in the last Constitution. Not only that, but you’re insane if you think that the Constitution is still relevant, or if you think that the Constitution was properly interpreted in Euclid and subsequent court cases regarding the state’s right to regulate land.

And you then tell us we cannot know what people “really†want anyway because their choices are tainted by past choices.

Past choices have some effect, but I’m not talking about past choices, I’m talking about current choices. Though you might think from reading the Antiplanner on a regular basis that mandatory low-density regulations are a thing of the past, you’d be dead wrong: they’re the most prevelant type of regulation, right here, right now. I didn’t think that the concept of government distorting the market to produce outcomes that don’t reflect people’s true demands was that controversial.

(Der Inspektor kann auch ein bisschen schreiben und sprechen!)

Eep! Sorry – no comment was deleted. My apologies.

Ettinger, “But in that case, proposing the reenginnering of cities seems even more absurd. Are we just blindly following along some herd trend?”

As far as smartgrowth and LRT are concerned the pollies are definitely doing just that.

But when it comes to arguing for the abolition of minimum lot size and minimum parking space regulations and arguing in favour of demand pricing for roads and kerbside parking, I get the feeling we’re not going to get killed in the stampede.

Ettinger, I can’t speak for everybody else but it seems to me America’s energy security, import bill, domestic economy and urban air quality are better reasons for reducing transport fuel use. Not what AP started with but very important, or at least it looks that way from where I sit in a tiny country in the middle of nowhere and even more at mercy of those factors than the USA is.

However to adress the issue of what happens to that 2%. Two points spring to mind as far as CO2 emissions are concerned.

1) That 2% might be used for petro-chemical feedstock instead of being burnt.

2) If extraction hasn’t peaked, either naturally or artificially, then the 2% is a real reduction in demand rather than being reallocated as would happen when supplies are constrained.

“Then what happens? OPEC decreases production? Why? Under what incentive?” To maintain the price at the profit maximisation point. This is where a price inelasticity between $25 and $125 becomes critical. Why sell for less than $125 if a price reduction will only have a minimal impact on volume sold? Ok, so I’m suspicious that the peaking of Mexican and North Sea oil has given the other oil nations the courage to flex their muscles and see just how inelastic oil demand really is. Why let the buyer dictate the price if the buyer needs to buy it more than you need to sell it. Might as well find out what the limit is and hold the price there. If you’re getting six times as much per barrel does it really matter if demand for oil drops by three-quarters? That just means your revenue stream will last six times linger, very important if you have a long range thinking culture.

“In other words, none of the current (and wannabe) oil consumers worldwide who currently line up to buy oil at $125 want to buy more oil to pick up that 2% left behind by US motorists?” Again this depends on current supplies being less than demand. That wasn’t a consideration at Kyoto when supply exceeded demand, and the countries creating the demand were excluded from the Kyoto protocol! Go figure.

So, IMHO, you’re half right and half wrong. Which is the more important half depends on whether the extraction plateau is “the” peak oil or an OPEC+ simulation and whether we are going to increased supply again in the future.

foxmarks, Thanks for the analogy. I can see why you are having trouble with the concept of tackling the easy part first. The short trips produce a quarter of all the auto CO2. That means the long trips produce three times as much CO2. That’s not a dribble and a gush comparison. It’s more a case of stuffing your t-shirt into the smaller of your two gushing holes to buy time while you get your trouers off to stuff them into the bigger hole.

If the short trips only accounted for a couple of percent of auto CO2 emissions I would agree with you completely. Which reminds me, isn’t that the sort of percent of CO2 that LRT tackles?

Kevyn,

And I now see that we would have to agree on the size/effect of the two gushes, which depends on our estimation of the CO2 feedback loops. If we’re all doomed by the large gush, why sacrifice to fix the small ones? If fixing the tiny gush is all that’s needed to save the ship, why do we need more than market forces to reduce carbon emissions? (if you buy my assertion that fuel costs will lead to fewer runs to the strip mall anyway)

And, I’ll still insist that, if stuff like energy security and air quality are the goals, we’ll get better outcomes faster if we price according to those goals, rather than some intermediate step like petroleum use.

It seems, if I agreed with your estimations and preferences, I would be a huge nuclear proponent.

foxmarks, If we’re all doomed by the large gush, why sacrifice to fix the small ones? Apart from buying time to think of a way to plug up the big gusher, there are a squillion good reasons – all of them of psychological rather than practical value. Being an optomist buying time is hugely important, you never know what will be invented or discovered tomorrow that could save our bacon.

“why do we need more than market forces to reduce carbon emissions?” Only one good reason: In an imperfect world market forces work imperfectly. Politics being the number one imperfection IMHO. In a perfect world we would have found some way to put a price on emissions. Unfortunately air and water are a little too mobile to fit easily into a property rights framework except by regarding contaminants as “tresspass” by those doing the contaminating. I guess this means I agree with your second paragraph.

Nuclear???? That’s soooo last century! Try hot-rock geothermal. That’s this century’s “dangerous” new source of infinite electricity so cheap it won’t be worthwhile metering!

Thanks Kevin. Those were exactly the counterarguments I had hoped for in order to make the discussion somewhat meaningful…

I had given some consideration to the factors that you mention (diversion to petrochemicals and OPEC oil price manipulation) but the uncertainty and volatility of such factors, still, hardly seems reason enough to reengineer cities.

And that is exactly the fallacy of central planning. Do politicians or expert committees know how much a 2% (or whatever) drop in oil demand will affect oil price? And they know the price level that will trigger as significant portion of the 2% saved, becoming absorbed by petrochemical uses? And that we should reengineer cities because we know that current high prices are due to the fact OPEC has now (why now?) become successful at manipulating oil prices and that it will/can continue to do so in the same manner in the future? If production is constrained artificially then a 2% decrease in demand is unlikely to defeat the manipulation anyway.

If the non industrialized world were to raise its per capita oil consumption to just 1/3 of the level in the industrialized world (US, Canada, Europe, Japan, Australia) oil consumption would go up more than 2 fold (and that is a conservative calculation). Isn’t that indicative of how deep oil demand is? Deep enough, seems to me, to completely absorb any savings in US cities.

That is why reducing CO2 from transportation in the US seems not much more than a feel good project (loaded with irrelevant agendas). “We’re doing our part even if it makes no difference in the end”. I guess if one feels good that by not using some of the oil extracted somebody else gets to use it, then indeed feeling good may be justified.

Ettinger,

The first thing I will add to this discussion is that the Kyoto protocol and the thinking behind it is a legacy of the era of supply outpacing demand. The situation you describe simply wouldn’t happen then. It’s a different story today.

Normally I am reluctant to accept the “if I don’t use it someone alse will” argument but in this case in the current fuel supply/demand situation it seems to be a valid argument. But let me be absolutely clear that this is not the energy efficiency rebound effect that we are talking here. The most thorough research into rebound for cars and household appliance identifies just 20% of the saving being directly used for more mileage or bigger appliances, etc. This is consistent with energy cost being a small part of total ownership or operating costs. So it’s not a case of if Americans downsize to cars from SUVs that they will drive further and end up using the same amount of fuel because they will simply use the amount of fuel that they can afford to use. That is why we see vmt falling only after the subprime crisis pushed up mortgage interest rates at the same time that oil broke the $100 dollar barrier. The nearly ten-fold increase in the oil price in the preceding six years had merely slowed the rate of vmt growth and altered the new vehicle sales profile. The latter only affects a small percentage of auto users each year so it would seem that Americans were prepared to reduce other discretionary spending to stay mobile.

Will they continue to do that when the sub-prime crisis has passed? Your guess will be as good as mine.

One thing that I do find intriguing in light of your argument is where have India and China been getting their extra oil from when official oil production figures show no real increase in almost the whole of this millenium? It seems, and I say seems advisedly, that the predictions made by some at the time that developing countries were exempted from Kyoto may have come true. The reductions occuring in oil consumption in both industry and auto travel in Europe and established Asian economies are being made up for by growth in the developing nations. In the case of industry this sounds ominously like Kyoto has triggered industry/employment exporting as the means of moving industrial CO2 emissions out of the developed nations CO2 inventories. Great for the developing nations but it does nothing to actually reduce CO2 emissions. Another planning boondoggle.

“Normally I am reluctant to accept the “if I don’t use it someone alse will†argument but in this case in the current fuel supply/demand situation it seems to be a valid argument.”

It’s not necessarily true. It depends on how the reduction is achieved. Most attempts of bullying car drivers out of their cars fail because 1) car drivers vote, 2) even if a reduction was achieved, no other region or country will follow suite – why would anyone go for a worse quality of life? – hence the surplus would get used up by others.

On the other hand, if the replacement for fossil fuels led to a higher quality of life (and there’s a big ‘if’ in there), other countries will follow suite, and people will vote for it. Fossil fuels will be left in the ground – the famous quote, that the stone age didn’t end because they ran out of stones – the new bronze tools were simply much better.

If technology manages to invent a marketable substitute for fossil fuels, then no regulations aimed at behavior modification are necessary. The technology will take over by itself. The Stone Age certainly did not end because of regulation against stone usage either.

And this is exactly the point…

If technology manages to replace fossil fuels with CO2 neutral options then no intervention is necessary. Subsidizing technology has a bad track record of success since it is virtually impossible for policy makers to second guess where the solution will come from (what policy makers would have guessed in the 60s that the solution to tailpipe emissions would come from the computer?). The risk is high that they will divert resources from the true but unexpected solution to the subsidies. But even if they could second guess, by how much could the policies accelerate the development? 1-2-5-10 years? Why risk an expensive, uncertain, politically mandated resource reallocation maneuver to perhaps gain 10 years on a possible threat that has a time horizon of 100 years or more?

If, on the other hand, technology cannot crack the problem, fossil fuel demand will remain so high that it will be impossible to keep the oil in the ground by regulation.

Ettinger, “(what policy makers would have guessed in the 60s that the solution to tailpipe emissions would come from the computer?).” None, or if any actually did make that prediction then the future has comprehensively proved them wrong. Attaching a computer to a typical mass production engine of the 60’s would hardly make any difference because the critical control systems aren’t there. However, attach your computer to Ford’s limited production Cosworth Formula One V8 with a commuter friendly camshaft and you instantly get today’s low emissions engine. Engineers new it could be done that’s why they did it. But to pay for the development the auto companies needed the incentive of regulation to overcome inertia from self-seeking customers – people tend to be altruistic only up to the point when they have to open their own wallet.

In a technocracy the probability of success can be estimated reasonably accurately for various research or developmental paths and resources can be allocated in proporion to those probabilities. In a democracy those assessments are subsumed by assessments of voter impacts, in much the same way that auto companies give precedence to potential sales impacts.

Fortunately emission regulations were a rare example of goal-oriented regulation. Limits were set along with implementation dates. It was then left up to each auto maker to determine the approach to meeting the challenge that would have the least market impact. Because customer resistance to cost internalization was the main reason the market hadn’t delivered clean air, regulation was needed to place every company in the same situation. Then it was up to the auto makers to compete to find the most customer friendly way of getting the job done. The big winner was a rank outsider. Honda cancelled it’s F1 program and set the designers of their V12 racing engines the task of producing a cheap, clean, fuel efficient, peppy engine within 4 years. The royalties from the resulting CVCC design provided the capital to launch the larger Accord into the American market half a decade earlier than originally planned. There’s always an entrepenuer who sees an opportunity where the big players only see a hurdle.

Pingback: American Dream News » Lexington, Kentucky - Enemy of the Environment?

Pingback: scale model trucks

Pingback: How Do I Doubt Thee? Let Me Count the Ways » The Antiplanner