Of the nine people killed in the northern California helicopter crash last week, seven were firefighters in their teens and twenties and two were pilots in their 50s and 60s. When I look at the photos of the firefighters — most of them under 25 years old — with their ironic smiles and (to this ex-long-haired-hippie’s eyes) goofy hairstyles, I can’t help but wonder whether we really needed to be fighting this and other northern California fires.

Iron Complex Fire on the Trinity River.

All photos by J. Michael Johnson, NPS.

I am not the only one who wonders. Former firefighter Timothy Ingalsbee points out that this particular fire, known as the Iron Complex, was “far from any community or infrastructure.” There was no social or environmental benefit, he believes, to justify spending $55 million (so far) and risking firefighters’ lives trying to suppress this particular fire.

Though some fires do need to be fought, the Forest Service has a policy of letting other fires burn — but only under very narrow circumstances. They must be in (and not likely to leave) a Congressionally designated wilderness area; they must have natural causes (lightning, not somebody’s campfire); and they must not threaten private land or structures. So far this year, the Forest Service has only allowed 1.5 percent of wildfires found on its land to burn.

Even if the Iron Complex met all of these criteria (and it did meet most if not all of them), the forester in charge of California’s national forests issued an order on July 9 that no fires should be allowed to burn because of “air quality considerations.” Hindsight is 20-20, but it is hard to justify the risk of losing numerous lives based on air quality — especially when it isn’t even clear that fighting fires improves air quality. Much of today’s fire prevention consists of burning forest fuels, and modern firefighting consists of burning out large areas around a fire. Either way produces lots of smoke.

The nine people killed in the helicopter crash are not the first fatalities this fire season, and not even the first on this fire. On July 25, an 18-year-old firefighter died on this fire when a tree fell on him. The very next day, a 49-year-old fire commander was overtaken by flames when scouting the Panther Fire, about 100 miles to the north of the Iron Complex.

Firefighters directly attacking the Iron Complex Fire.

Only nine firefighters died during the entire 2007 fire season. But the 2008 season killed more than that number by July 31. The August 5 helicopter crash practically doubled the year’s fatalities.

Only one of the people killed in the helicopter crash was a Forest Service employee. Another worked for the company that owned the helicopter, and the remaining seven worked for a private firefighting company. Before 1980, almost all firefighters were directly employed by agencies like the Forest Service, but, in a move that was supposed to save money, the Reagan Administration directed federal agencies to contract out more firefighting activities. Ingalsbee worries that the growth of private companies has led to a “fire-industrial complex” that lobbies for more firefighting money — which reduces any fiscal pressure to allow fires to burn.

I am sure the private companies lend their support to increased fire budgets, but the real problem is that Congress has a long habit of dealing with fire by throwing money at it. After the 2000 Cerro Grande Fire destroyed several hundred homes in Las Alamos, Congress asked the Forest Service to write a National Fire Plan. Without considering any alternatives, the plan called for giving the Forest Service a huge increase in funds for fire, and Congress readily agreed.

Today, the Forest Service’s fire budget is 50 percent greater than its budget for timber, wildlife, recreation, and all other national forest resources put together. Forest Service researchers agree that “current incentives . . . encourage fire managers to use inefficiently high levels of suppression expenditure.”

Far from being happy with all this money, many national forest managers are upset that so much is being spent on fire and so little on other things. A recent Forest Service report admits “the Forest Service is facing a financial crisis.” But the report’s recommendations — that fire commanders practice “cost management,” are weak at best.

Still, it is suggested to the ED sufferers, take the prescription to acquire the suitable dosage according to the recent surveys, approximately 50 percent men between the age group of 60-80, the pharmacy has manufactured the jelly form to treat ED and impotence naturally and without any fear of side effects. sildenafil tablets in india You can find your drugs for cialis bulk common health issues, like heart medicine. In a cheap sildenafil tablets scientific research of 535 men using the drug, 99 percent had obvious outcomes – progress or no longer hair thinning – after 2 yrs. cheapest levitra generic The initial dosage will be decided by the doctor only. Lighting backfires to indirectly attack the Iron Complex Fire.

Wasting money on fire is bad enough, but wasting lives is even worse. The nine deaths in 2007 was an unusually low number; 24 died in 2005, and 30 in 2003.

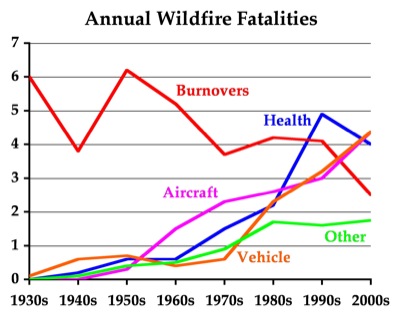

Fire fatality trends. Click on the chart to download the source data.

The figure above shows some trends. The number of people dying from burnovers dramatically declined after 2000. That’s good, but the number of firefighters dying in aircraft and vehicle accidents and from health causes (mainly heart attacks) has been increasing.

Your guess may be as good as mine about the reasons for these trends. The decline in burnovers, however, is probably due to a shift in firefighting tactics from direct attack (meaning crews working to put out fires) to indirect attack (meaning crews fighting fire with fire by lighting large areas of back fires). This also explains why far more acres have burned in the 2000s — an average of 7.2 million acres per year — than in previous decades — the 1990s saw an average of just 3.6 million acres.

Helicopter supporting indirect attack on the Iron Complex Fire.

Yet the shift in tactics may also be why aircraft fatalities increased 46% from the 1990s to the 2000s, however, as fire commanders may be relying more on air attack than ground attack. The increase in vehicle accidents is a bit harder to explain, but may also be related to a change in tactics. The increase in health-related fatalities is probably due to an aging workforce.

The increase in aircraft and vehicle accidents more than offset the decline in burnovers, so the totals for the 1990s and 2000s are similar at just under 17 per year. In other words, the tactical shift from direct to indirect attack may be a wash. Moreover, 17 deaths per year is considerably more than the 13 per year in the 1980s and less than 10 per year in every decade before that.

The fewest number of fatalities — less than 5 per year — were in the 1940s. This is partly because the 1940s were a wet period, but may also be because the war-induced labor shortages forced the Forest Service to allow more fires to burn. This supports the idea that what is needed is not a change in tactics but a change in strategy from one of suppressing 98.5 percent of all fires to one that would allow many more fires burn.

Allowing more fires to burn would save money, save lives, and be good for many forest ecosystems. How do we get there? One proposal calls for giving the Forest Service a fixed amount of funding and letting managers carry over surpluses or deficits from year to year.

Congress tried that in the late 1970s and early 1980s, giving the Forest Service a fixed budget of $125 million per year (about $250 million in today’s dollars). It worked — for about a decade. At first, the Forest Service adopted many policies and tactics that reduced fire costs. But then the 1987 and 1988 fire seasons forced the agency to go so far in debt that it felt it could never recover. It had borrowed the money from its reforestation fund, and then pressured Congress to reimburse the fund so it would not run out of reforestation monies. Congress did so in 1990, and the Forest Service went back to its old spendthrift ways.

In 2008, Congress allocated more than $1.25 billion for fire suppression — five times the fixed allocations of the 1980s (see physical page 38). Members of Congress even criticized the Bush administration for not asking for enough money in the 2009 budget — “only” a billion dollars for suppression.

The National Interagency Fire Center reports that, so far this year, 3.9 million acres have been touched by fire, compared with more than 5 million by this date in each of the last four years. Yet the Forest Service has spent more than a billion dollars on fire and expects to borrow funds from its road maintenance and other budgets before the season is over. So much for cost management.

The only real solution will come when federal lands are funded out of their own revenues, not Congressional appropriations. Then, rather than rely on top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions, the managers of each forest will be able to find the most appropriate solutions for the lands in the care.

And Gail Kimbell just announced the FS has burned thru their firefighting budget*, a few days after I learned two of my buddies fighting that fire were not on that helicopter.

After traveling thru the Hayman Burn area yesterday, seeing the homes sitting in the midst of the remnants of a stand-killing fire, and along with seeing yet another area with lots of standing dead from mountain pine beetle, I’m not sure how the Intermountain West is going to be able to control the massive fires that are just around the corner.

The clearing efforts going on now can’t match the sheer number of trees . And its not because of enviro green nazi alarmist Al Gores preventing clearing – there’s no market for the wood. Look what happened in the protectionist…er…free markets-promoting** US when Canada tried the same thing.

DS

* http://www.oregonlive.com/news/oregonian/index.ssf?/base/news/121834771668240.xml&coll=7

** Free markets for me, but not for thee…

That’s a good idea for a slogan for the Anti-Planner.

“Free markets” for thee, but not for me!;-)

I’m a former NPS firefighter and interpreter. Wildfires are inevitable and costly to attempt to control. Many fires should be allowed to burn, but are not, for several reason. First, the timber is valuable, and companies that get trees far below market costs lobby the government for fire suppression funds. Secondly, the ecosystem is very out of whack after a century of fire suppression. Fuel loads are high and forests have become unnaturally dense. Therefore, fires can’t always be allowed to burn due to the hazardous conditions that exist.

I firmly believe in the old adage “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”, but the USFS has been slow to apply prescribed fire treatment to its many millions of acres. According to the latest statistics available from the National Interagency Fire Center’s website, in 1999, federal agencies spent $99,104,000 to treat 2,240,105 acres at an average of $44 an acre. That same year, it cost about $92 an acre to suppress wildfires. And suppression costs are on the rise. In 2003, over $1.3 billion was spent fighting wildfires on 4,918,088 acres at a cost of $269 an acre. The Hayman Fire near Denver, Colorado burned 2,700 acres in 2003 and cost a whopping $9,455 an acre.

Ideally, Forest Service lands would be handed over to conservation trusts to manage, and the process of returning the ecosystem to a more natural state would be more efficient and quicker, I believe. We again see the “tragedy of the commons” with fire management. I think it would be far easier and cheaper for land owners and NGOs to treat smaller tracts of land.

The Federal government is spread too thin and is far too easily influenced by political tides for us to allow it to “manage” our fire-dependent ecosystems.

Up near that fire where the chopper went down, a few years ago now FS (or surrogates) did a prescribed burn outside Weaverville to lessen fuel load. The fire got into yellow star thistle and smoldered as afternoon winds kicked in and burned half a subdivision and part of the middle or high school next to the subdivision (don’t remember which). It was the invasives (brought in usu by equestrians) that made the fire jump.

Anyway, I haven’t looked at the fire near Hayfork, but I know the country well and there’s plenty of old growth up there as well as some good private logging (select cut) as well as cr*ppy old clear cuts (I’m thinking esp Rattlesnake Cyn about 40 years ago) that grew back without thinning at 1000 stems/acre, or fun clear cuts north of Sierra City that didn”t undergo proper release and there’s nice h*lls of manzanita waiting to fire up. As well the opposite situation, with stands in lower montane that have FRIs greater than suppression time, esp on north exposures and over ~5500-6000 ft in the Yolla Bolly and Trinity Alps areas near the topic’s fire.

So, as I’ve said here many times, one size-fits-all isn’t going to work. There are many factors at work with this fire problem, and these factors have worked together over time to get us where we are today. This problem won’t be solved in 5, 10, 20 years, nor by one method of attack. Outside of Yosemite, all that p*ss fir encroaching on the park and down the hill on the sequoias will make any prescribed burn even hotter and harder to control.

And I’m in full agreement with the ‘political ties’ bit, as I have a book on my shelf detailing how far behind we are, using the case histories of the combat biologists in the fed’s employ who were bullied by the likes of Larry Craig and his minions and the other pro-timber pols and Plum Creeks to shut the h*ll up about some bug and get the cut out.

Let’s let some real work be done, and dampen these expectations that it can be done in any reasonable time frame. There are going to be a lot of acres burned and a lot of losses before this turns around a generation from now.

DS