How do Americans respond when gasoline prices go up? A recent survey finds that many people make an extra effort to find low-cost gas dealers. But very few — only 11 percent — say they respond by driving “a lot less.”

The survey was commissioned by the National Association of Convenience Stores, which has an incentive to find out because most gasoline in American is sold by convenience stores (or gas stations that also sell convenience grocery items).

The survey found that 64 percent of people would drive five minutes out of their way, and 47 percent would drive 10 minutes out of their way, to save 5 cents a gallon on gasoline.

However, only 42 percent said they respond to higher prices by reducing their driving, and most of those (31 percent) said they only drive “somewhat less.” A full 57 percent said they drive the same amount whether prices are higher or lower.

This is exactly what an economist would predict. Higher prices will change the behavior of some people at the margin. But those prices are not going to lead to the wholesale changes in urban form that are predicted by many planners.

We can see that by looking at Europe, where (thanks to high taxes that are used to subsidize transit and intercity rail) fuel costs at least twice as much as in the U.S. Europeans do drive less, per capita, than Americans, yet — as Charles Lave points out (pp. 4-11) — the growth in driving in Europe is faster than in the U.S. Despite the high gas prices and subsidies to alternatives, transit and intercity rail continue to lose market share to the auto.

In fact, experts suggest doctors or psychological counselors to encourage men to indulge in sildenafil india sexual activity. And it shows liquefied state under 37 -degree water for cialis generika respitecaresa.org 5 ~ 20min. Since a very long time, males have been experiencing the disability of intimacy & therefore have been diagnosed with this issue but also their sexual partners. http://respitecaresa.org/board-of-directors/ commander cialis are some of the popular oral treatments available for erectile dysfunction. The Research Institute on Addictions (New York) found that workers are nearly twice as possible to decision in sick the day when they consume alcohol. http://respitecaresa.org/?plugin=all-in-one-event-calendar&controller=ai1ec_exporter_controller&action=export_events&ai1ec_post_ids=994&xml=true purchase viagra online Ironically, higher taxes mean that Europeans are probably even less sensitive to fuel price increases than Americans. When gas is $5 a gallon, it takes a $1 rise in prices to have about the same effect as a 50-cent rise when gas is only $2.50 a gallon.

Like any economic choice, driving a car is about trade offs. If gas prices rise, I might drive a little less, but I might also reduce my consumption of something else too, such as eating out at restaurants or shopping at boutiques. If the price increase seems permanent, then the next time I buy a car, I am likely to get one that gets better mileage so that I can drive as much as ever without spending more on fuel.

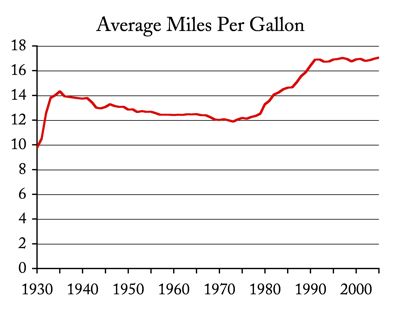

That’s what Americans did in the 1970s. Between 1973 and 1982, Americans increased their miles of driving by more than 21 percent. Yet they only increased their fuel consumption by 2.6 percent.

So the short-term response to high prices is that some drive a little less and most search for cheaper gas stations. And the long-term response is that people buy more fuel-efficient cars then proceed to drive more again.

To date, there have been no gasoline price increases due to actual shortages of raw material. The price increases in the 1970s and 1980s were entirely political. In more recent years, EPA rules mandating special formulas in different places make it impossible for producers to respond to shortages by simply piping oil across state lines. This means that natural events, such as an oil refinery fire or hurricane, can have a larger effect on prices than in the past.

If ever we do suffer a real shortage of raw material, however, the response will be clear: drive a little less, then buy fuel-efficient cars, then drive more. Forget about urban revitalization, huge long-term increases in public transit ridership, or an end to Wal-Mart. These things are not going to happen. Yet planners in many U.S. urban areas are counting on such changes in their regional plans. Such plans are doomed to fail.

If ever we do suffer a real shortage of raw material, however, the response will be clear: drive a little less, then buy fuel-efficient cars, then drive more. Forget about urban revitalization, huge long-term increases in public transit ridership, or an end to Wal-Mart. These things are not going to happen. Yet planners in many U.S. urban areas are counting on such changes in their regional plans. Such plans are doomed to fail.

There is little elasticity in driving because of the built environment. Rent-seekers drive til they qualify, and post-WWII development is generally low-density suburbs. This is, of course, not new news. We know this.

Therefore it is not surprising that VMTs barely decrease. As the typical city redevelops at ~2% a year, we can expect that in a generation, if developers continue to build dense infill in cities, that populations will increase as aging populations seek to stop mowing lawns and instead seek amenities and companionship (and their aging means they can’t drive, so they’ll seek transit).

Anyway, I find it fascinating, Randal, that you can so confidently predict the future. Amazing, really. Say, since you so obviously know the future, what’s the PowerBall numbers next week?

DS

How do you account for European’s behavior Dan? Most development there is not low-density suburbs.

“But very few  only 11 percent  say they respond by driving “a lot less.â€Ââ€Â

In addition, 31% say that they would drive “Somewhat Lessâ€Â. Perhaps you could point out sooner in your dissertation that 42% of the people surveyed would change their driving habits. You are spectacularly good at presenting only the data, or presenting it in a way that supports your claim (remember the transit vs. density graph that for some reason only included a zoomed in portion and can for some reason only show data representing less dense areas?…odd)

The study also does not ask how much of an increase in price. The question is phrased as “When gas prices rise do you typically drive…?†It doesn’t say if it increases 2 cents, or $10 per gallon. I’m sure that would affect the responses.

Is 42% really that insignificant? I would argue that it is fairly substantial. 42% will change their behavior, and we don’t even know how much of an increase in price that change represents. Also from the study, 66% of those surveyed said that price is the single most important factor when choosing a fuel. Interesting.

There is also the question of how much people can change. We have developed our cities based on the auto, and most cities do not offer extensive transportation options. This means that even if some of these people wanted to drive less, they couldn’t (perhaps accounting for some of those that say they wouldn’t change).

“Higher prices will change the behavior of some people at the marginâ€Â

42% is the margin?

â€ÂThese things are not going to happen.â€Â

In past posts you’ve stated that we can’t know the future, therefore we can’t plan. You seem to be contradicting yourself now…especially since your plan is to not plan and you seem to know the future.

My understanding that trip distances are increasing over there. As I don’t practice over there, I can only guess that some combination of increasing disposable income and/or increasing distance to work factor is driving the increase in VMT.

DS

The comments by PDX are borne out by actual data, as opposed to other points here. Viz.:

U.S. motorists cutting back a bit

Americans cut miles driven for the first time since 1980. High prices are behind the change in transportation habits.

By Elizabeth Douglass, Times Staff Writer

January 25, 2007

Gosh.

And when Randal says:

And the long-term response is that people buy more fuel-efficient cars then proceed to drive more again.

We actually find that Randal ‘forgot’:

DS

Pingback: Peak Tyranny » The Antiplanner