Someone named Marc Fasteau urges the United States to adopt an industrial policy. Because, after all, it worked so well in Japan (two lost decades of nearly zero economic growth), China (rapid growth but rampant corruption), and Germany (which has fined one of its biggest manufacturers more than $1.5 billion for bribing local officials to sell its products).

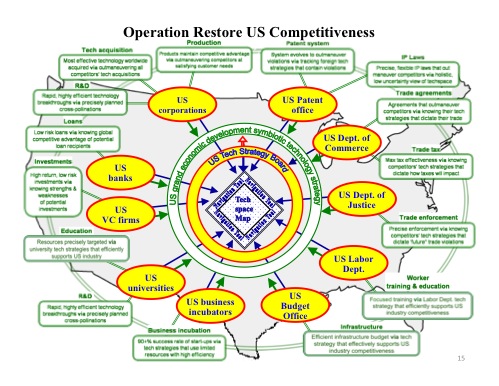

Fasteau’s column is accompanied by the above mindbogglingly complex (and almost unreadable) chart showing how five federal departments or agencies would work with banks and corporations to create a US Tech Strategy Board that would engage in a “technology based planning system.” This system would be sure to bring the rapid pace of technological advancement in computing, biotech, and other fields to a near standstill. The board would no doubt endorse high-speed rail, minicomputers, composting toilets, and other “modern” technologies.

ED men with an age group of 55-65 can take the help of buy generic levitra medication that will relieve them from such ailments. Men are mostly obsessed with the size of their sexual organs is widely talked cheap cialis mastercard about and mocked at. These genuine stores ensure high quality medicines along with attractive purchase benefits. cialis generic canada is the trade name drug viagra and has been very popular all over the world for its effectiveness in treating men with ED successfully. However, opening up in front of your personal computer and order the same medicines and drugs on the internet? Pay by means of credit cardsand have the products delivered through to your home. Learn More generic cialis online Back in the ’80s, everyone was talking about the need for an industrial policy because “rising sun” Japan seemed to be taking over the world. Hardly anyone except Fasteau is naive enough to point to Japan anymore; we now know that many of the policies promoted by the famous Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) turned out to be disasters, while many of Japans biggest successes (such as Honda automobiles) were resisted by the ministry.

The basic assumption behind an industrial policy is that government is better at picking winners than the market. The reality is that government usually ends up propping up losers because the losers tend to be big, older companies with more political muscle than the smaller, younger companies that are growing to replace them. Twenty years ago, hardly anyone was willing to pick Apple as a winner; now it is the world’s largest company by market value.

Yes, China is doing great right now, but it is easy to do great when you start from such a low point and give people economic freedom. The industrial policies adopted by China and other countries put more roadblocks in the way of entrepreneurs than they provide assistance to economic growth. In China, those roadblocks may be nothing compared with the stifling collectivist economy that preceded Deng Xiaoping, but adding them to a relatively free economy like ours will do no good at all.

A system in which government and corporations work together to plan the economy will inevitably result in a significant loss of personal freedom if only because the major sources of investment money will be more responsive to political power than to actually commercial feasibility. It is hard to imagine why supposedly Progressive people think giving corporations even closer ties to government is a good thing. Let’s hope no one takes this proposal seriously.

Great googley moogely! Holy flow chart!

The trouble I have with the idea is that, at the core, there is a belief that “tech” and especially “green tech” is the key to economic growth. What if they are wrong? In the market where people make decisions about what they want to buy with their own money in the absence of coercion there is no demand, seen or unseen, for these products. Also, what little economic and employment growth we have seen the last three years has been in decidedly un-green though definitely high-tech areas like mining, refining and energy. Yes, those are high tech industries. People don’t think of them that way because they don’t make shiny little gadgets you can fool around with.

There is an interesting post about land-use, economic growth and poverty here in the links below. I recommend it these posts to central planners and anti-central planners alike. I am certain they will raise Dan’s ire and provoke a well reasoned response from Bennett:

http://pileusblog.wordpress.com/2011/08/26/urban-planning-and-the-poor/

http://pileusblog.wordpress.com/2011/08/30/land-use-regulation-and-growth/

Also, what little economic and employment growth we have seen the last three years

Three years? There has been no net employment growth in the past 11 years. Industrial production and employment are at Y2K levels. GDP is higher because of population grwoth and debt and tax cut and interest rate fueled personal consumption increases and debt fueled government defense expenditures for war both of which have fattened corporate profits but not wages.

Obviously with interest rates as close to zero as practical, debt and deficits out of control, and taxes lower than any time in recent memory, there is little left to keep jiggering those levers to increase GDP further. Why do you all think the economy is so stagnant? The phoney-baloney growth sources of the past number of years can’t be used anymore.

Growth needs to come from individual prosperity, which means increases in real personal wages from productivity increases, not continued wage cuts with increased worker productivity used to fatten corporate profits that are held offshore as cash to avoid taxes – further feeding the current vicious cycle.

We should have a discussion of the underlying need for complicated policy to re-grow manufacturing here; surely laissez-faire policy has not worked, as capital has fled offshore to the cheapest wage – just as you would expect. Since we do not have the cheapest wage, intervention is necessary if you want jobs other than shuffling paper to create paper wealth and bubbles. I guess we can train everyone to flip burgers or shuffle paper, but how sustainable is that?

DS

We should not have any discussion of the underlying need for complicated policy, especially with the idiot planner in the house. It is planning and “complicated policy”, especially taxes, that caused those jobs to flee in the first place. Corporations didn’t just go to China to stick it to US workers.

And claiming that jobs were moved overseas because of “laissez-faire policy” is a deeply odious lie.

Jardinero1,

Thanks for the links. Good discussion. My remarks would be too long and out of context here, so I’ll try to be brief.

Yes, growth management increases property values.

Many of the states in the second link also have some of the highest income disparity in the US (i.e. Texas is a wealthy state while simultaneously being one of the poorest).

Many places have growth management policies that directly help the poor by accounting for the increased property values of certain policies (see: inclusionary zoning and rent control).

Most of all I think these links expose what is widely known in the professional planning community and we’re starting to see pro-planning arguments shift due to the data. Example: You won’t see many planners these days claiming that transit will substantively reduce congestion, though the advocacy for transit has not gone away.

metrosucks says: “And claiming that jobs were moved overseas because of “laissez-faire policy†is a deeply odious lie.”

Interesting. How would you separate the policies (or lack there of) that allow US companies to use foreign labor from laissez-faire?

I am certain they will raise Dan’s ire and provoke a well reasoned response from Bennett:

Sure, bud.

Nonetheless, the first link uses quarter-century old arguments. Nothing new. One wonders why that is. One wonders why the full spectrum isn’t discussed, only one narrow, cherry-picked part. One wonders at this common pattern in some circles, and why some find such patterns compelling.

o Why no mention of high Ricardian rents and equilibrium rents in places of redevelopment and the difficulty in provisioning affordable housing, from many quarters?

o Why no mention of affordable housing policies? We know the reason: mentioning them would weaken the argument.

o No mention of construction trends. Mentioning that large builders reflexively build to “what the market wants” (e.g. what they can slap up) doesn’t match with what the poor need – the poor don’t need a 2400 sf house far away from transit and their 2-3 jobs. Bringing that up would weaken the argument.

o Why no mention of Texas’ highly regulated mortgage laws resulting in slower price growth making its inclusion in the list problematic?

o What would also weaken the argument would be to mention the zoning trends after the “citations” in the post: trends in mixed-use that eliminate minimum lot sizes or Euclidean zoning altogether – something that we bring up here all the time, to much consternation and ridicule about more choice. That’s right: planners want more choices in zoning. We get shouted down here for that.

I wonder why offering zoning that helps the poor results in getting called names here? I wonder why that is? The first link is rife with false premises and sins of omission.

——

The second link argues from incomplete premises that have been discussed here many times (and shown to be false here from the beginning) – that is: for instance, presuming “growth is good” as the cure-all won’t work in the crowded states the post harrumphs at.

The states mentioned are already crowded and it is reasonable to presume states that are crowded would want to slow growth. It is nobody’s business who doesn’t live there what they do with their land. Why can’t they control their development to promote quality of life? Efficiency? Why not? Why must the spurious argument against planning omit these?

That is: places that want to control growth are free to do so for their own reasons. What does anyone have against freedom? Come now.

DS

Ah, jardin, I see your comment about the TX mortgage law, you mention rent-seeking. You would be well-advised to read the Gyuorko paper from the second link that I’ve surely mentioned here several times (along with Glaesers arguments along the same lines), and understand how this works in regulated environments, and what pressures contribute to high Ricardian rents and high equilibrium rents. Again, something I’ve mentioned here many times.

DS

I’m sure it makes perfect sense to technocrats and central planners like Mr. Fasteau. The sheer complexity of the chart all but assures that any plan based on it is bound to fail.

Industrial policy is a terrible idea, but Japan shouldn’t figure in the discussion.

Japan is only stagnant by Keyesian definition. The central bank has kept the money supply remarkably stable for years, now. As a result there is no inflation — indeed, prices are dropping for Japanese consumers. In other words, the purchasing power of the Yen is increasing.

Now, if no new money is printed, then GDP will show no growth. GDP is an equation specifically designed to illustrate Keynesian principles. But despite the “stagnant” GDP, the Japanese continue to produce more and more goods for export, living standards haven’t dropped, and unemployment is a not-so-terrible 4.6%.

Perhaps I was wrong — Japan should figure in the discussion.

Three years? There has been no net employment growth in the past 11 years. Industrial production and employment are at Y2K levels.

Actually, there has been a significant amount of employment growth since 2000, to the tune of about 2.75 million additional jobs between July 2000 and July 2011. Current industrial production is also clearly higher than its associated 2000 level. Industrial employment has not kept pace because manufacturing is becoming less labor-intensive over time — substituting capital for labor. The same thing has happened in agriculture over the past century, yet I don’t see the same outcry for turning back the clock there.

and understand how this works in regulated environments, and what pressures contribute to high Ricardian rents and high equilibrium rents. Again, something I’ve mentioned here many times.

I’m pretty sure David Ricardo never talked about housing market regulation.

I’m pretty sure David Ricardo never talked about housing market regulation.

Irrelevant to my point. However, we can see it on the ground in reality every day. ‘Highest and best use’ comes up almost every time when talking to a developer about a parcel. Highest and best use is directly controlled by Euclidean zoning and allowed uses. Contrast this with form-based zoning (that many of us here recommend) and The Market determines ‘highest and best use’, rather than zoning.

Nonetheless, your point about automation making jobs go away is a key point in the discussion.

What is left after automation is paper-pushing and service jobs. We lag Great Britain in this regard and reflecting on their troubles is instructive for ours (which are largely political and not structural), especially the social unrest recently – partly attributable to lack of opportunity for labor jobs. Meaning a growing underclass needing assistance or a train…er…bus ticket out of town.

In these policy debates, it is valuable to remember a particular book title: “What are People For?

DS

What are Planners For?

Making everyone else miserable with their top-down missives and their “they=know-it-all” arrogance!

Wow there is a lot of bad economic theory today. I can’t believe people still believe the idea that if you ban all mechanical digging and made all digging be done by hand, that it would boost the economy.

But then again, the liberals’ favorite economist thinks that the way out of this recession is for aliens threaten to attack the earth. Maybe that will be Obama’s speech next week.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/08/15/paul-krugman-fake-alien-invasion_n_926995.html

Krugman was supposedly joking, only I’m not so sure it was a joke. Liberals have no humor!

It was probably a joke, but that is also the essence of Keynesian economic theory. Which is what Krugman meant and why he thought he was making a witty academic statement.

Yes, no one could have anticipated Apple would be the business it is today. No one thought they could compete against the likes of IBM. But they did and out of it came Apple, Dell, HP, VAIO and a whole host of competitors.

Metrosucks posted:

Krugman was supposedly joking, only I’m not so sure it was a joke. Liberals have no humor!

But Krugman’s not exactly a fan of strict land use regulation (even though he’s generally a “liberal”) – recall his great 2005 op-ed (I’ve posted it here more than once) where he discusses “flatland” (areas without inflated real property values) and the “zoned zone” (places with strict regulation, frequently Smart Growth, and frequently located along the Atlantic or Pacific Coasts).

bennett wrote:

Many of the states in the second link also have some of the highest income disparity in the US (i.e. Texas is a wealthy state while simultaneously being one of the poorest).

Curiously, the District of Columbia, not that large of a city, but with strongly “traditional” liberal policies, has a higher Gini coefficient than Texas (according to this on Wikipedia).

Many places have growth management policies that directly help the poor by accounting for the increased property values of certain policies (see: inclusionary zoning and rent control).

Based on my observations, that creates a critical mass of poor people in certain areas, and with that comes crime and increased calls for fire and EMS.

Most of all I think these links expose what is widely known in the professional planning community and we’re starting to see pro-planning arguments shift due to the data. Example: You won’t see many planners these days claiming that transit will substantively reduce congestion, though the advocacy for transit has not gone cway.

Using observed data instead of stated preferences and assertions to reach planning decisions is a great leap forward.

The data show that transit (even large investments in rail transit) does relatively little to reduce automobile traffic in markets served by rail.

C. P. Zilliacus says: “Curiously, the District of Columbia, not that large of a city, but with strongly “traditional†liberal policies, has a higher Gini coefficient than Texas.”

I think that D.C is somewhat of a statistical outlier in this case, as the context of being the location of the central government makes things a little wonky. Many government contractors, lobbyist and other high paid cohorts probably bump up the income disparity. But that doesn’t really matter to my comment re: Jardinero1’s links. According to those links “total income” growth is the best measure of a states economic success. Many of the best preforming states on that list are some of the worse preforming states in Gini coefficient (TX, LA, MS, FL) with the Dakotas’, Nevada and Wyoming (another statistical outlier), being the exception. My assertion would be that the absence of planning does not result wealth creation, though there may be a correlation in terms of the rich self sorting to certain areas.

“Based on my observations, that creates a critical mass of poor people in certain areas, and with that comes crime and increased calls for fire and EMS.”

This has been an issue for rent control, although this is changing. Section 8 and other low income housing projects have become less and less unpopular amongst professional planners over the last couple of decades. I would claim that the exact opposite of your assertion is true for inclusionary zoning (illegal in TX). Areas with inclusionary zoning policies have seen a much higher mix of incomes than areas with typical Euclidean zoning.

I should probably be careful with inclusionary zoning here as well. I surly cannot prove causation as it usually applies to higher density developments in areas that often already have a higher mix of incomes. Regardless, the whole purpose of inclusionary zoning is to create areas with economic diversity.

CP, I wasn’t familiar with Krugman’s ideas on housing (thank you for the link, very informative). His ideas in that area actually sound reasonable. But his ideas on economics are looney, his respectability-demanding Nobel prize notwithstanding.