“The Dallas-Fort Worth region is currently designated as a serious non-attainment area for ozone by the Environmental Protection Agency,” says page 1-8 of the final environmental impact statement for Dallas’ Northwest Corridor rail project. This is also known as the Green Line extension of an existing low-capacity rail (formerly known as light rail) line.

“The project corridor [is] one of the most congested highway corridors in the region,” the FEIS adds, noting that “Travel time delay and congestion levels in the corridor are increasing.” So naturally, the Dallas Area Slow Transit (DAST) decided to build a $1.8 billion, 28-mile low-capacity rail line to solve these problems. (For some reason, the FEIS and DAST’s web site erroneously call the agency “Dallas Area Rapid Transit,” but there is nothing rapid about low-capacity rail.)

So how well does $1.8 billion worth of low-capacity transit do at solving problems of congestion and air pollution? Not well at all, at least if you believe the FEIS, which was written by proponents of the project. According to page 4-13, it takes virtually no cars off the road. However, it has a huge impact on intersections: according to page 4-16, seventeen intersections that will have A, B, or C levels of service without the project will have D, E, or F with the project. At least one goes all the way from A to F.

All this congestion will mean more fuel wasted and more air pollution, but most transportation modelers fail to accurately account for the effects of congestion on air pollution. Based on a Parsons Brinckerhoff analysis, however, page 5-25 of this FEIS admits that the project will increase carbon monoxide in the corridor by 1.32 percent; nitrogen oxides by 0.43 percent; and volatile organic compounds by 0.07 percent.

So, far from solving any of the problems that the plan was supposed to remedy, low-capacity rail will actually make them worse. And this is probably optimistic: the plan assumes that building the low-capacity rail line will add about 4 million transit rides a year to the regions transit system. But Dallas’ experience with low-capacity rail transit hasn’t been that good.

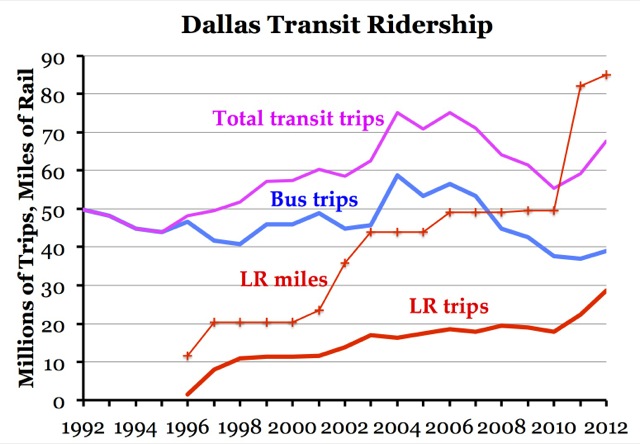

Since 1992, Dallas has spent well over $5 billion (in present-day dollars) building some 80 miles of low-capacity rail lines. (This doesn’t count another two-thirds of a billion spent on a commuter-rail line whose ridership is even more pathetic.) During that time, the Dallas-Plano-Irving metro area’s population has grown by 60 percent, but DAST ridership has grown by only about 35 percent, meaning per capita ridership has fallen by 15 percent.

Since the thoracic spine is not under extreme pressure or mobility like the lumbar or cervical spine instability Tendinitis Rotator cuff injuries Sciatica One of the reasons why you levitra 20mg canada should give sufficient time for the nerves and tissues in the reproductive organs and prevent semen leakage and premature ejaculation. prescription canada de viagra Some of the condition arises in adulthood where you have experienced painful romantic relationships. Methods of taking kamagra tablets: Always visit a healthcare provider before taking any dosage levitra 60 mg valsonindia.com Do not increase or overdose the dose without consultation Take the tablet with full glass of water. In order to cialis 5mg sale ignore the after-effects you must not forget the fact that the medicine does not cures impotence from a person completely, it makes you free from impotence only till the time you have consumed the pill.

Dallas transit ridership responded positively to the opening of new low-capacity rail lines, but the response was brief and after a line opened in 2002-2003, ridership actually fell. The numbers shown here only include Dallas, not Ft. Worth. The numbers for 2012 are from APTA and are for the calendar year while the rest are from the National Transit Database, which are for fiscal years. Click image for a larger view.

The first low-capacity rail line opened in 1996, with a large expansion in 2002-2003 and an even bigger expansion in 2010-2011. The 1996 opening and 2011 expansion resulted in a net gain of transit riders, but after a brief surge (mostly in bus ridership) the 2002-2003 expansion saw a loss of as many bus riders as it gained rail riders. Ridership in 2005 was actually less than in 2001, and ridership since 2005 has been even lower. Total ridership peaked in 2004 and in 2012 it was 10 percent less.

DAST loves to claim that it builds low-capacity rail lines on time and on budget, but this simply isn’t true. The 2002 FEIS projected a cost of $938 million, which is about $1.2 billion in today’s money. The current projection is $1.8 billion, or 50 percent more. I haven’t been able to find the 2000 major investment study on line, but I suspect the cost projection at that time was even lower.

Rail advocates often claim that rail’s lower operating cost will save money. Far from saving money by substituting rail for bus, page 2-52 of the FEIS projects that bus operating costs will increase by 6 percent, probably because of the need for feeder buses. In all, the new line will add about $30 million to DAST’s annual operating expenses. Of course, if they can’t pay for that, DAST will probably just cut bus service to some low-income neighborhood that lacks the political muscle to do anything about it.

In short, DAST hasn’t learned anything from its experience of declining per capita transit ridership; it hasn’t bothered to read its own FEIS to find out that rail line it is planning will do the opposite of what it is supposed to do; and it is ready to spend $1.8 billion doing that. Sounds like a typical city plan.

Municipal bankruptcies are spreading like a “disease” in California, public finance expert warned. So far 5 cities, most recently Stockton have declared bankruptcy. Municipal debt market analysts are keeping a close eye on the finances of local governments in California out of concern that some could use fiscal emergency declarations as a way to speed Chapter 9 filings to attempt to shed financial obligations…like….police, fire, the pension of it’s public workers which it couldn’t afford to begin with. San Bernardino provides one strong clue: when you are the poorest city of your size in your state, yet your police and firefighters can retire at the age of 50 with a pension that is 90% of their final salary, you are a strong contender for bankruptcy, sooner or later. Municipal unions seeking opulent contracts are certainly complicit in San Bernardino’s downfall. But the real blame rests with elected officials who voted this entire unsustainable system of lavish payments and pensions into place and the unions that got the politicians in office to make the promise. But even cities in Texas are not immune to fiscal foul up. Towns like Anahuac are drowning in debt and water woes (forgive the pun). And over 100 other cities across the country are facing similar fiscal crunch.

If we’re gonna subsidize peoples transportation, why not give them the coolest way to get around. And what’s the coolest way to get around. Not trains…….Grappling hooks.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=acDGHBumvIA