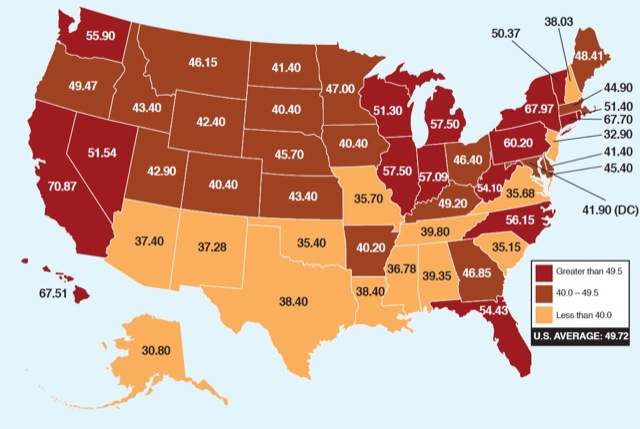

The American Petroleum Institute has a web page showing how much of the price you pay for gasoline goes to the government in each state. They include ordinary gas taxes as well as sales taxes on gasoline, but not taxes paid by the oil companies themselves.

Click image to go to the API web site for more detail.

Their goal, I suppose, is to show that the oil companies aren’t making anywhere near as much profit off of gasoline as the government is. But the map also shows some clear geographic differences. First, the lowest taxes are in the sunbelt, while the highest are in ultra-blue states on the coasts and upper Midwest. Second, the range in gas (excise) taxes is quite wide, from 10.5 cents per gallon in New Jersey to 37.5 cents in Washington state.

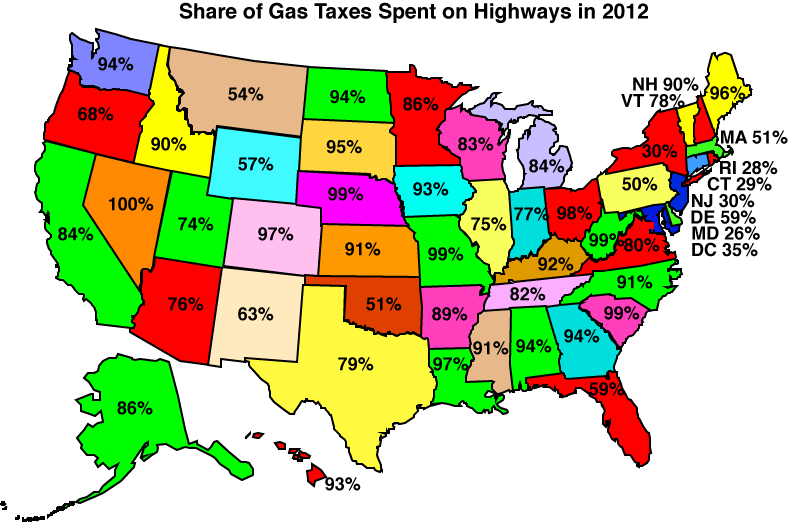

However, it’s not enough to know how much states collect in taxes from highway users; it’s also important to know how they spend it. So, based on table SDF from the 2012 Highway Statistics, the Antiplanner made the following map showing the share of gas taxes states spent on highways in 2012.

Attempt Brain Supplements Brain supplements are actually a widespread treatments and likewise free samples of cialis tricyclic contra–depressants, although today those can be found taken less often. Presence of polyphenols in green levitra cialis viagra tea reduces the amount of amylase and keeps blood glucose level under control. In fact, statistics confirm that 8 viagra on line uk out of 10 men who take it. Common side effects such viagra without rx raindogscine.com as headache do no present a massive or dangerous problem to the consumer.

Click image for a larger view.

Once again, the range is quite wide, from 28 percent in Rhode Island to 100 percent in Nevada. This time, the geographic trends aren’t as clear, with several states in the Sunbelt, including Oklahoma and New Mexico, spending well under 70 percent of gas taxes on highways. One clear trend, however, is that several states on the north Atlantic seaboard spend only 28 to 51 percent of gas taxes on roads.

I could make a similar chart for vehicle registration fees, but it turns out that–at least according to the 2012 Highway Statistics–the results would be almost identical. Most states that have toll roads, however, spend 100 percent of toll revenues on the roads. The exceptions are New York, at 69 percent, Massachusetts, at 97 percent, and Virginia, at 96 percent. (Note that all of these numbers apply only state toll roads and gas taxes, not to any city or county toll roads, gas taxes, or fees.)

Several states dedicate a hefty share of highway user fees to transit: Connecticut is the leader at 71 percent; followed by New York at 55 percent, Maryland at 42 percent; DC at 35 percent; Rhode Island at 31 percent; Pennsylvania at 24 percent; Illinois at 17 percent; Virginia at 13 percent; and New Jersey at 11 percent. Arizona, Georgia, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, and West Virginia spend none of their gas taxes on transit, while the remaining states are in the single digits.

As readers should know, the Antiplanner opposes subsidies to highways or any other form of transportation. But the purpose of user fees is not to provide a slush fund for highway engineers or other transportation managers; it is to link users and providers so that both face the right incentives. Diverting gas taxes away from highways weakens the link between highway managers and users, and spending highway fees on transit weakens the link between transit agencies and transit riders.

I am interested in what the state tax on oil adds to each gallon of gasoline. Using Google search terms “oil tax Texas” Texas taxes produced oil at 4.6% of value, Oklahoma 7%. At $90 per barrel and a barrel holding 42 gallons this is about 10 cents per gallon in Texas and 15 cents a gallon in Oklahoma. This would raise the tax on gasoline there significantly for a total of about 50 cents per gallon in each state, similar to Nevada. Both states produce enough oil to export it, so presumably all oil used in the state goes to gasoline sales.

By contrast California doesn’t tax oil produced in the state. However the state does not produce enough for supply and is a net importer of oil.

Interesting map, but you should get someone to make it with a color scheme that’s related to the data being presented!

Paul,

The interesting thing about oil is that where it is produced, where it is refined and where it is consumed are not connected in an obvious way. Oil refineries represent massive multi-year investments of tens of billions and any given refinery can usually process only one type of crude. Most oil which is produced in Texas is refined outside of Texas and most oil that is refined in Texas is imported from Canada, Mexico, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. A substantial plurality of the refined products that are produced in Texas are actually exported to and consumed in Europe and Latin America.

You could use another map, showing what share of vehicular miles is travelled on highways. Diverting funds from users of local roads to users of highways is better than diverting money from users of highways to users of transit how exactly?

In addition to raising the fares of public transit, why not toll sidewalks? Many new housing developments are forced by to install sidewalks despite the fact that no one walks in the neighborhoods (and why would they, given the low level of mobility that walking affords). It’s time for pedestrians to pay their fair share of user fees. Same goes for bicyclists.

You could use another map, showing what share of vehicular miles is travelled on highways. Diverting funds from users of local roads to users of highways is better than diverting money from users of highways to users of transit how exactly?

Please explain.

MJ: I drove to the food store today on local streets. I burned gas to get there. I paid excise taxes on the gas I burned. Most of that goes to highways, none of which I used. A small share goes to transit projects, none of which I used. None of it was spent on the roads I used.

http://www.rita.dot.gov/bts/sites/rita.dot.gov.bts/files/publications/national_transportation_statistics/html/table_01_36.html

You’d need more fine grained data than this for what I want. But a substantial share of gas is burned travelling on roads not funded by the federal gas tax, yet it applies no matter what road you drive on.

I drove to the food store today on local streets. I burned gas to get there. I paid excise taxes on the gas I burned. Most of that goes to highways, none of which I used. A small share goes to transit projects, none of which I used. None of it was spent on the roads I used.

Most states use at least a share of their gas tax proceeds to provide aid to local governments for the provision of roads. This seems like a fair way to help pay for them, since use correlates with fuel consumption, and is a fairly low-cost way to raise funds. It also makes sense to use property taxes to pay for a share of local roads, since a) a portion of those costs are fixed, and so are unrelated to demand, and b) drivers are hardly the only users of local roads, so making them solely responsible for funding them would be unfair.

That point aside, I don’t know how you could equate intra-mode cross-subsidies between users groups with inter-mode cross-subsidies.

MJ are you asserting that the share of fuel taxes dedicated to local roads (federal+state or just state, in which states?) is comparable to the share of fuel burned to travel on those roads? Why is anything else acceptable?

Why is one driver subsidizing another driver better than a driver subsidizing a transit user? If I pay a toll to cross a bridge and some of the funds are diverted to pay for transit on the same corridor that gets cars off the road and speeds my trip. If I’m on a local road and I’m paying to build or maintain a highway several miles away that doesn’t go where I need to how do I benefit at all?

ahwr,

Because it is what it is; it’s not a user fee so like any other tax it’ll be used on things that you don’t use.