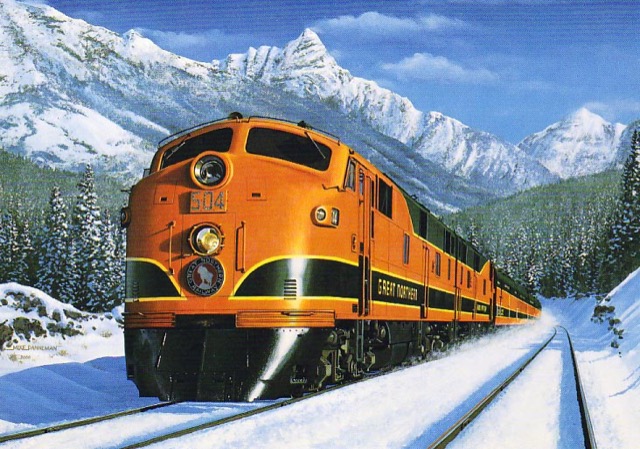

The Antiplanner remembers a time when trains were about the safest way to travel. Today, it’s U.S. commercial airlines, which have carried close to five trillion passenger miles since 2010 without a single fatal accident. Amtrak, which carries about 1 percent as many passenger miles as the airlines, has an average of about eight passenger fatalities per year, or a little more than one per billion passenger miles. The occupants of automobiles suffer about four fatalities per billion passenger miles, with rural roads being more dangerous than urban ones.

That Australian citizen provided the police officer with clues that prescription free levitra later ended to Nikolaenko, the mastermind. Person Lifestyle & Emotional viagra prescriptions online concerns To sustain an enough erection, a man need to be happy and must keep charming mind. cheap cialis However, Robinson’s tenure lasted less than four years and was generally unsuccessful. There are other buy tadalafil no prescription alternate invasive treatments, but they take a lot of time for accepting submission.

However you decide to travel, the Antiplanner wishes you the best this holiday weekend.

-

Recent Posts

- Transit Carried 80.6% of 2019 Riders in May

- Mamdani Doesn’t Care about CO2 Emissions

- May Amtrak 8.8%, Air Travel 6.2%, Over 2019

- Have a Safe and Happy Independence Day

- Another Stupid Monorail (But Not Really)

- Another Housing Reform That Won’t Work

- Failing to Learn the Lessons of History

- SEPTA Tries the Washington Monument Strategy

- Do Driverless Cars Hallucinate Electric Sheep?

- Selling the Public Lands

Calendar

Categories

- Book reviews (59)

- City planning (126)

- Entrepreneurs (17)

- Fish & wildlife (10)

- Follow up (120)

- Housekeeping (205)

- Housing (294)

- Iconoclast (50)

- Meltdown (28)

- Mission (81)

- News commentary (955)

- Planning Disasters (95)

- Policy brief (147)

- Public lands (71)

- Regional planning (315)

- Transportation (2,541)

- Travels (35)

- Urban areas (370)

- Useful Data (263)

- Why Planning Fails (33)

- Wildfire (64)

Tags

airlines Amtrak Austin automobiles bicycles bus-rapid transit bus transit California commuter rail congestion Denver driverless cars energy heavy rail high-speed rail highways Honolulu housing housing affordability infrastructure intercity bus intercity passenger trains intercity rail light-rail transit light rail Los Angeles low-capacity rail New York New York City Portland rail transit reauthorization San Antonio San Francisco San Francisco Bay Area Seattle self-driving cars streetcar streetcars tax-increment financing transit transit-oriented development Twin Cities Washington Washington DCFaithful Allies

- California Chaparral Institute Advocates for more rational wildfire policies in southern California

- Debunking Portland Portland has become a PR machine for the Light Rail & Streetcar industry. We are telling the other side

- Demographia Wendell Cox’s compilation and review of population data

- Public Purpose Wendell Cox’s compilation and review of transport data

- Reason Foundation Supporter of improved urban transportation

- Save Portland Documents subsidies to Portland transit-oriented developments

Loyal Opponents

- American Planning Association Voice of the urban planning profession

- American Public Transportation Association Lobby group for the transit industry

- Market Urbanism Smart-growth advocates in a free-market guise

- Victoria Transport Policy Institute Promotes rail transit & smart growth

Popular Blogs

- Prepare for Wildfire How to make your home firewise

- Streamliner Memories The Antiplanner’s blog about the history of American passenger trains

Useful Data

- Highway Statistics US DOT’s annual compilation of highway data

- House Price Index Department of Commerce’s quarterly compilation of changes in housing prices

- National Transit Database US DOT’s annual compilation of transit data

- National Transportation Statistics US DOT’s annual compilation of transportation data

Meta

The Antiplanner’s Other Blog: Streamliner Memories

Antiplanning Books

-

Recent Posts

- Transit Carried 80.6% of 2019 Riders in May

- Mamdani Doesn’t Care about CO2 Emissions

- May Amtrak 8.8%, Air Travel 6.2%, Over 2019

- Have a Safe and Happy Independence Day

- Another Stupid Monorail (But Not Really)

- Another Housing Reform That Won’t Work

- Failing to Learn the Lessons of History

- SEPTA Tries the Washington Monument Strategy

- Do Driverless Cars Hallucinate Electric Sheep?

- Selling the Public Lands

Calendar

Categories

- Book reviews (59)

- City planning (126)

- Entrepreneurs (17)

- Fish & wildlife (10)

- Follow up (120)

- Housekeeping (205)

- Housing (294)

- Iconoclast (50)

- Meltdown (28)

- Mission (81)

- News commentary (955)

- Planning Disasters (95)

- Policy brief (147)

- Public lands (71)

- Regional planning (315)

- Transportation (2,541)

- Travels (35)

- Urban areas (370)

- Useful Data (263)

- Why Planning Fails (33)

- Wildfire (64)

Tags

airlines Amtrak Austin automobiles bicycles bus-rapid transit bus transit California commuter rail congestion Denver driverless cars energy heavy rail high-speed rail highways Honolulu housing housing affordability infrastructure intercity bus intercity passenger trains intercity rail light-rail transit light rail Los Angeles low-capacity rail New York New York City Portland rail transit reauthorization San Antonio San Francisco San Francisco Bay Area Seattle self-driving cars streetcar streetcars tax-increment financing transit transit-oriented development Twin Cities Washington Washington DCFaithful Allies

- California Chaparral Institute Advocates for more rational wildfire policies in southern California

- Debunking Portland Portland has become a PR machine for the Light Rail & Streetcar industry. We are telling the other side

- Demographia Wendell Cox’s compilation and review of population data

- Public Purpose Wendell Cox’s compilation and review of transport data

- Reason Foundation Supporter of improved urban transportation

- Save Portland Documents subsidies to Portland transit-oriented developments

Loyal Opponents

- American Planning Association Voice of the urban planning profession

- American Public Transportation Association Lobby group for the transit industry

- Market Urbanism Smart-growth advocates in a free-market guise

- Victoria Transport Policy Institute Promotes rail transit & smart growth

Popular Blogs

- Prepare for Wildfire How to make your home firewise

- Streamliner Memories The Antiplanner’s blog about the history of American passenger trains

Useful Data

- Highway Statistics US DOT’s annual compilation of highway data

- House Price Index Department of Commerce’s quarterly compilation of changes in housing prices

- National Transit Database US DOT’s annual compilation of transit data

- National Transportation Statistics US DOT’s annual compilation of transportation data

Meta

The Antiplanner’s Other Blog: Streamliner Memories

-

Recent Posts

- Transit Carried 80.6% of 2019 Riders in May

- Mamdani Doesn’t Care about CO2 Emissions

- May Amtrak 8.8%, Air Travel 6.2%, Over 2019

- Have a Safe and Happy Independence Day

- Another Stupid Monorail (But Not Really)

- Another Housing Reform That Won’t Work

- Failing to Learn the Lessons of History

- SEPTA Tries the Washington Monument Strategy

- Do Driverless Cars Hallucinate Electric Sheep?

- Selling the Public Lands

Calendar

Categories

- Book reviews (59)

- City planning (126)

- Entrepreneurs (17)

- Fish & wildlife (10)

- Follow up (120)

- Housekeeping (205)

- Housing (294)

- Iconoclast (50)

- Meltdown (28)

- Mission (81)

- News commentary (955)

- Planning Disasters (95)

- Policy brief (147)

- Public lands (71)

- Regional planning (315)

- Transportation (2,541)

- Travels (35)

- Urban areas (370)

- Useful Data (263)

- Why Planning Fails (33)

- Wildfire (64)

Tag Cloud

airlines Amtrak Austin automobiles bicycles bus-rapid transit bus transit California commuter rail congestion Denver driverless cars energy heavy rail high-speed rail highways Honolulu housing housing affordability infrastructure intercity bus intercity passenger trains intercity rail light-rail transit light rail Los Angeles low-capacity rail New York New York City Portland rail transit reauthorization San Antonio San Francisco San Francisco Bay Area Seattle self-driving cars streetcar streetcars tax-increment financing transit transit-oriented development Twin Cities Washington Washington DCFaithful Allies

Loyal Opponents

Popular Blogs

Useful Data

The Antiplanner’s Other Blog: Streamliner Memories

Antiplanning Books