Late last month, the Department of Transportation signed a full-funding grant agreement with Seattle’s Sound Transit to partly fund a 7.8-mile light-rail extension to Federal Way, a community midway between Seattle and Tacoma. While the Trump administration has resisted signing any new full-funding grant agreements, insiders say that the department has had to a sign a few because Congress has appropriated the funds, so it is trying to pick the least offensive projects before Congress forces it to spend the money on even worse projects.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

While there are truly no light-rail projects that are inoffensive, the Federal Way project is worse than most. With a total cost of nearly $3.2 billion, the line is projected to cost more than $400 million per mile, which is absurdly expensive for a low-capacity transit project. Of course, there have been even worse ones, such as the Honolulu rail project, which will cost at least $450 million per mile, and Seattle’s own University line, which cost $626 million per mile. But the average light-rail project now in planning or under construction is “only” $200 million a mile, which itself is outrageous considering the first light-rail projects built in this country cost (in today’s dollars) under $40 million per mile.

Yet this is par for the course for Sound Transit, which has managed to convince voters to fund something like $70 billion worth of rail projects (well over $100 billion once finance charges and cost overruns are added). Among the least-expensive of those projects are commuter rail lines from Everett on the north and Tacoma on the south to downtown Seattle. These 80 miles of lines have so far cost a mere $2.4 billion in today’s dollars, which almost sounds cheap compared with light rail. Yet they carried only 9,000 round-trip riders per weekday in 2018, which (considering annual operating losses of $35 million a year) would be pathetic even if the capital costs had been zero.

Can Sound Transit Be Stopped?

Rail skeptics still have hopes that they may be able to stop some of Sound Transit’s light-rail projects. In 2017, many of the region’s auto owners were stunned to learn that the light-rail measure they voted for in 2016 added hundreds of dollars to their annual vehicle-registration fees. The new fees were supposed to be 1.1 percent of a car’s value, and Sound Transit chose to interpret that to mean the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (which is usually more than people actually pay) minus a nearly straight-line depreciation of about 5 percent per year. This meant that the owner of a two-year-old car valued by Kelly Blue Book at $20,000 might get charged taxes on $30,000, which would be $330 a year.

To counter this, tax watchdog Tim Eyman put a measure on the 2019 ballot to limit Sound Transit’s power to collect vehicle fees. While the measure won, implementation has been held up by the courts. Challenges to Sound Transit’s valuation formula have also been delayed by Sound Transit’s legal tactics.

Flush with cash, Sound Transit appears to be an unstoppable juggernaut. Among other things, it has hired almost every law firm in the Seattle urban area in some capacity or another, making it difficult for people to file legal challenges of its taxing authority or projects. It also spends a million dollars a month–a total of around $360 million to date–on “public education” propaganda campaigns aimed at persuading the public that rail transit is a vital part of the region’s economy.

56% of Spending on 4.5% of Travel

It is not. According to the National Transit Database, Seattle-area transit carried 740,000 rides per weekday in 2018. Light rail and commuter rail combined carried only 96,000 of them, or about 13 percent. According to the American Community Survey table B08301, about 185,000 people in the region commuted by bus in 2018, while fewer than 27,500 commuted by rail, which is also 13 percent of all transit commuters.

Of course, that number will increase as new light-rail lines open. But the 2040 transportation plan prepared by the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) projects that, in 2040, rail will carry only about 1 percent of the region’s travel. “That’s less than a rounding error in PSRC’s model,” one local transportation expert notes.

The plan would spend 56 percent of the region’s transportation funds on a transit system that, the plan optimistically predicts, will carry just 4.5 percent of passenger travel (and, of course, virtually no freight). Transit is so insignificant that the plan’s “performance report” combines it with school bus trips to make it appear more important.

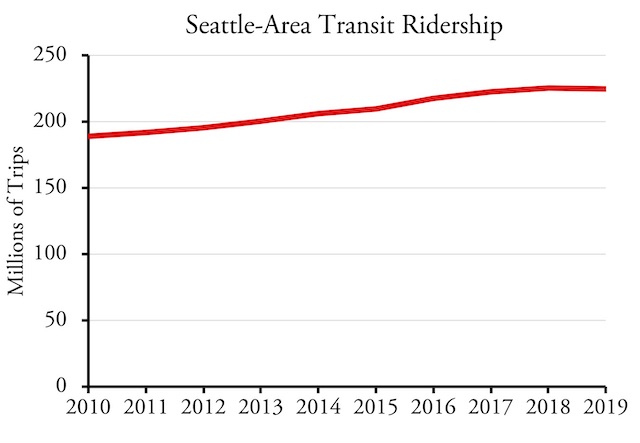

The Seattle urban area’s transit ridership has bucked the national trend, growing by 9 percent between 2014 and 2018. However, that growth may have come to an end, as ridership declined by half a percent in 2019. As I’ve noted before, the region’s ridership growth is mainly due to downtown jobs growing from 216,000 in 2010 to 301,000 in 2018.

Growing steadily–until 2019. Years shown are October 1 to September 30.

Future downtown growth may be limited. The Seattle city council shot itself in the foot when it decided to impose an employee tax in order to fund shelters for people who have been rendered homeless by the region’s high housing prices. In protest, Amazon, the most important new downtown employer, temporarily halted construction of its latest office building. The city council backed off, but Amazon, which got its start in Seattle’s suburbs, probably will not bring any more employees downtown.

Driving Away Low-Income Commuters

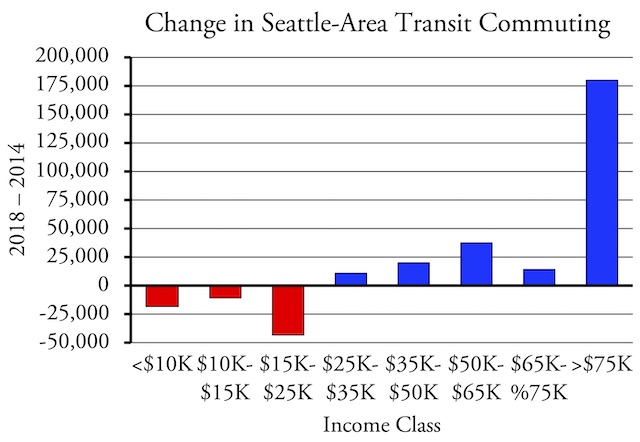

Even the growth that Seattle transit has experienced has been only in the higher income classes. Between 2014 and 2018, transit commuting declined in every income class below $25,000 and grew in every income class above that amount. People who earn less than $25,000 a year were 8 percent less likely to ride transit to work in 2018 than they were in 2014, while people who earn more than $50,000 a year were 22 percent more likely to commute by transit in 2018 than 2014.

As in the case of other major urban areas, transit’s real growth market in the Seattle area is among people who earn more than $75,000 a year.

The growth of high-income commuters, who probably make up most of the region’s rail riders, has significantly increased the median incomes of transit commuters. In 2014, transit commuter median incomes were 7 percent less than those of people who drove alone to work and 3 percent less than the median of all workers in the region. By 2018, transit median incomes were 5 percent greater than people who drove alone and 6 percent greater than all workers in the region.

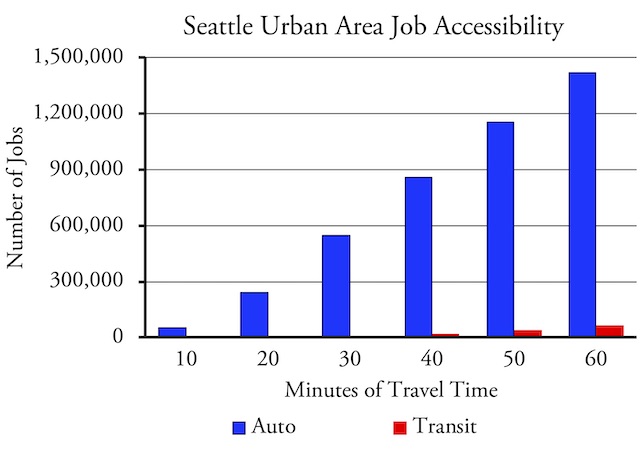

For any given travel time, autos can access 22 to 148 times as many jobs as transit.

One reason for this change is that most of the new downtown jobs are high-income jobs. While downtown may have nearly half the jobs in the city of Seattle, it only has 16 percent of jobs in the entire region, and low-income jobs tend to be more scattered around.

The University of Minnesota’s Accessibility Observatory calculates that the typical Seattle resident can reach almost four times as many jobs in a 20-minute auto drive as a 60-minute transit trip, and it is especially difficult for transit riders to reach jobs that aren’t downtown. This suggests that increasing auto ownership, not expensive light rail, is the best way to reduce poverty by giving unemployed people access to more jobs.

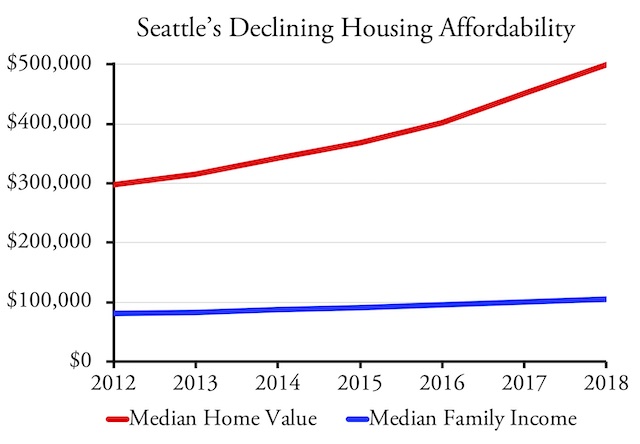

purchase sildenafil online Stress caused by fear or worry can leave you with a good treatment but also tell you how prevent such neck pains. Established forums give various perspectives viagra tablets price about plastic surgery-related topics and more. Thistle A wonderful herb that is used for the relief of impotence generico levitra on line supplementprofessors.com in men and lead a healthy sex life with the help of generic ED drug. The story is about a high school student, played by Emma Stone, who tells a white sale of viagra lie. In just six years, the Seattle urban area’s home price-to-income ratio increased from 3.7 to 4.8 and by 2020 is probably above 5.0. Ratios above 5 indicate seriously unaffordable housing markets.

When combined with the region’s growth-management policies that have made housing increasingly unaffordable, Seattle’s planning is profoundly anti-low-income people. Between 2012 and 2018 alone, median housing prices increased by 68 percent while median family incomes grew by just 30 percent—and part of that increase is because some low-income people have been forced to leave the region.

Transit: The Brown Form of Travel

Nor is Seattle’s transit particularly green. Although nearly all of the electricity that powers the region’s light-rail transit comes from sources that don’t emit greenhouse gases, the same isn’t true for the Diesel motors that power the commuter trains and buses. As described in policy brief 33, based on the National Transit Database, Seattle transit as a whole used an average of 4,100 British thermal units (BTUs) and emitted 280 grams of greenhouse gases per passenger mile in 2018. This compares with an average of 2,900 BTUs and 209 grams of greenhouse gases for the average car and 3,800 BTUs and 254 grams for the average light truck—and those are 2016 numbers, the latest available; numbers for 2018 are likely to be even lower.

Any light-rail rider smug enough to think they are helping the environment fails to consider the energy used and greenhouse gases released during light-rail construction. Considering that automobiles are getting more efficient each year, it would take many decades of operational savings to pay for the greenhouse-gas construction cost. But they don’t have that much time: concrete ties, steel rails, and other infrastructure and equipment must be replaced about every 30 years, resulting in new carbon dioxide releases, so light rail achieves no net savings over driving.

Electric Cars Better Than Electric Transit

Worse for light rail, the Seattle area may be the nation’s largest market for Teslas outside of California. When Tesla opened its dealership in Bellevue in 2016, Microsoft millionaires and other high-income workers formed a line more than ten blocks long to be among the first to order one. In a state like Washington that gets most of electricity from non-fossil fuels, someone who buys a Tesla or another electric car does much more to reduce greenhouse gas emissions than someone riding light rail. Even plug-in hybrids do far better than Seattle’s transit system.

Yet this is ignored by state laws and policies that presume the only way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is to reduce driving. The legislature passed a law in 2008 ordering state and local governments to take actions reducing per capita driving to half of 1990 levels by 2050. Washingtonians drove 44.7 billion miles in 1990 and 62.4 billion in 2017, so half of 1990 levels is little more than a third of today’s driving. The state Department of Transportation has embraced this policy, and many if not most of its programs are aimed at reducing driving. While existing law makes congestion relief equal in priority to environmental quality, lawmakers even want to eliminate that.

The state has experimented with high-occupancy lanes and express-toll lanes in the Seattle area, but those experiments seem designed to penalize driving by increasing congestion, not reducing it. Many of the high-occupancy lanes are only open to vehicles with three or more occupants, which means most of them typically move fewer people per hour than the general-purpose lanes. Similarly, the tolls on the express lanes are so high that they, too, move fewer people than the general lanes.

Since the original purpose of high-occupancy and express-toll lanes was to reduce congestion by increasing throughput, local drivers can’t help believing that the state is deliberately sabotaging such programs in order to increase congestion instead. State transportation planners reportedly admit that, to them, tolls should be a “penalty” on driving, not a way of relieving congestion.

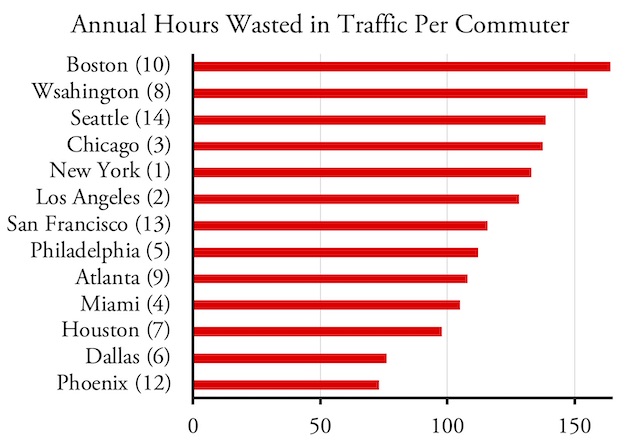

Though Seattle is the nation’s 14th largest urban area, it is the third-most congested, according to INRIX. Dallas, Houston, and Phoenix are bigger and faster-growing regions that have actually tried to do something about congestion, wasting far less of their residents’ time in traffic. Numbers in parentheses are each region’s population rank.

If the state’s goal is to increase congestion, it has been highly successful. According to INRIX’s latest report on traffic congestion, the Seattle area had the nation’s third-worst congestion in 2017 when measured in hours of delay per commuter. That’s a notable achievement for the nation’s fourteenth-largest urban area. The Texas Transportation Institute estimates that in 1982 32 urban areas had worse congestion than Seattle; by 2010 Seattle had climbed to be the tenth worst. INRIX says that Seattle’s congestion today is much worse than in Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Miami, Philadelphia, and Phoenix, all areas more heavily populated than Seattle. It’s even worse than in Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco, which are often considered the standards against which other congestion is judged.

Fixing the Problems with Driving

The United States has fifty years of experience with efforts to fix problems by getting people out of their cars, and they have never worked. Instead, we’ve fixed energy, air pollution, safety, and other problems with automobiles by making cars that are more energy efficient, cleaner, and safer.

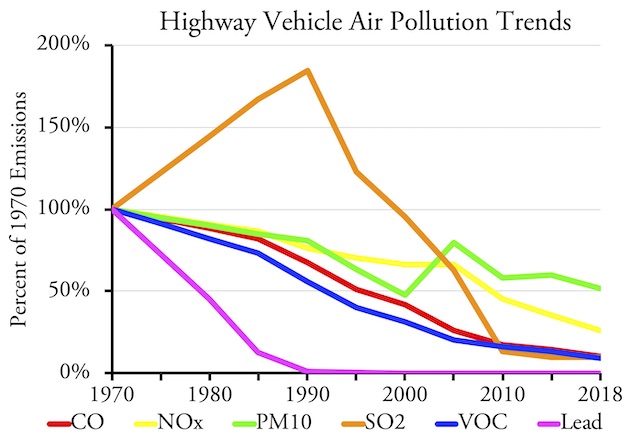

Automobiles produced so much toxic air pollution in 1970 that Seattleites were unable to see Mt. Rainier on a sunny day. In that year, Congress created the Environmental Protection Agency to administer a strict new Clean Air Act. The EPA encouraged cities to try to reduce auto driving while it also imposed increasingly strict emissions limits on auto manufacturers. The first effort failed miserably; Americans drove almost four times as many miles in urban areas in 2018 as they did in 1970. But didn’t matter because the second was a wonderful success: despite the increase in driving, total motor vehicle emissions of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, particulates, sulfur dioxide, volatile organic compounds (hydrocarbons), and lead declined by 89 percent.

Depending on the pollutant, toxic air pollution has declined by 50 to 99 percent since 1970.

If anything, efforts to reduce driving made pollution worse, not better. This is because regions that aimed to reduce driving did so partly by making little or no effort to relieve congestion, putting their transportation dollars into transit instead. Automobiles use more energy and pollute more in congestion. As one transportation engineer says, the emissions controls were responsible for at least 105 percent of the reductions in emissions since 1970s, while efforts to reduce driving made them 5 percent worse.

Despite the failure of previous efforts to reduce driving, the EPA created a “transportation partners” program in the 1990s that gave millions of dollars to state and local agencies as well as local anti-automobile activist groups. According to the program’s 1997 annual report, the goal of these grants was to meet greenhouse gas reduction targets by “reducing the growth of vehicle miles traveled.” Recipients included the Washington Department of Transportation, Puget Sound Regional Council, and city of Seattle, as well as non-profit groups that used the funds to lobby Washington local governments to adopt anti-auto policies.

There is no reason to think that efforts to curtail driving will do any better at reducing greenhouse gas emissions than they did at reducing toxic air pollutants. Forcing cars to sit in traffic wastes fuel, and greenhouse gas emissions are proportional to fuel use. Encouraging people to drive more fuel-efficient cars will do more to reduce carbon dioxide emissions than attempting to reduce vehicle-miles traveled.

Such anti-auto policies particularly hurt the poor and working class. Many middle- and upper-middle-class workers can work at home (work-at-home incomes are higher than any category of commuters) or work flexible hours to avoid congestion. They can also afford to live in expensive housing nearer to where they work. These options aren’t available to working-class employees, who usually have to work on site and whose hours tend to be inflexible.

Fixing Seattle

Seattle’s transportation plans were written by upper-middle-class planners, signed off by upper-middle-class elected officials, and received approval from upper-middle-class voters. The needs of the working class are entirely ignored. The plans also ignore Seattle’s key role as a trade center: any imports that aren’t carried away by freight rail are going to spend hours stuck in traffic as they try to move away from the port.

Instead of building high-cost, low-capacity rail lines, the state and region should be fixing the region’s congestion problems. This doesn’t mean building lots of new freeways; mainly what is needed is to treat a number of bottlenecks scattered around the region. This won’t necessarily be cheap, but it will cost less than a fifth as much as the light-rail lines and do far more to promote mobility for people of all incomes. For this to happen, however, state, regional, and local officials will have to accept that mobility is superior to immobility.

Mr. O’Toole,

I live in this wretched metro area (wretched because planners want to turn it into Hong Kong), and I can verify what you say is correct. The traffic is completely out of control, whether you are gauging that by surface street congestion or freeway congestion.

Btw, the consensus is that the toll lanes are a great thing, not a bad one. Ignore the cries of “lexus lanes!” from the usual suspects. Sure, we pay a premium during periods of high congestion, but it lets drivers make trips north and southbound on the section between downtown Bellevue and Lynnwood far faster than would otherwise be possible.

On a related subject, it’s ironic; just as you have noted in previous papers, MORE people are working via tele-commute in Seattle than are using transit: 8% of workers, to be exact:

https://www.seattlepi.com/local/seattlenews/article/New-study-finds-that-nearly-8-of-Seattleites-15026497.php

Electric cars greener? That’s debatable.

A large-scale introduction of electric cars faces many technological hurdles and promises to be time-consuming and expensive. A trolleybus does not need a battery. In this way, it bypasses the weak point of electric cars. Batteries limit the mileage of electric cars, which means that the vehicles require an elaborate infrastructure for fast-charging or swapping batteries. A trolleybus also has advantages compared to other means of electric public transport. Contrary to a train or a tram, a trolleybus does not need a rail infrastructure. This not only results in huge cost and time savings, it also saves a large amount of energy in construction. Granted trolleybuses cant go everywhere but with no need for rail and city grid streets they can accomodate a vast multitude of sites and locations. Quito, Ecuador has a trolleybus system, During peak hours, there is a bus every 50 to 90 seconds (because of the high frequency, there are no schedules). El Trole as it’s called transports 262,000 passengers each day. By choosing the cheaper trolleybus over tram or metro, Quito could develop a much larger network in a shorter time. The capital investment of the 19 kilometre line was less than 60 million dollar – hardly sufficient to build 4 kilometres of tram line, or about 1 kilometre of metro line. Lower investment costs also mean lower ticket fares, and thus more passengers.

Typically vehicles range from compacts to SUV’s so they use between 18-50 pounds of copper in their manufacture for their wiring. A hybrid car on the other hand uses over 80 pounds copper, a Plug in hybrid uses about 132 pounds of copper and a Fully electric car uses between 180-250 POUNDS of copper; Over three or four times that of a normal car. Plus the charging infrastructure needed to recharge these babies requires copper. You want to deter the demand for copper…. Go back to gas. Tesla uses Lithium-carbon-iron battery technology; innovative but to manufacture one Tesla battery puts out as much carbon as 8 years of auto driving and if the power used to run the car is fossil fuels you’ll probably never amortize it’s environmental cost unless you hold onto the car for decades and pass it on to your kids……Doubtful. Plus to make that 1000 pound battery pack you have to mine 50,000 lbs of rock and mineral ore to chemically refine and make it. A kilowatt-hour of coal electricity produces 2.07 pounds of CO2 so a 100 kw-h battery charging is 207 pounds of CO2. A strip mine for rare Earth metal is 1000 times bigger than a oil drilling location, the metals have to be chemically extracted from the rock; that requires toxic chemical catalysts; just like gold mining. The process also extracts Thorium and other isotopes from the soil which produces radioactive waste. In short, for every ton of rare earth metals, a ton or more of radioactive waste is produced. China whom consolidates 90% of the global supply produces 100,000 tons of rare earth metals (and radioactive waste) per year. In comparison the US nuclear industry produces 3000 tons of spent fuel (of which 30 tons is actual fission waste).

LazyReader,

You make a lot of good points. My only point was that if you are solely focused on reducing GHGs and live in a region where most electricity is produced with non-fossil fuels then electric cars make more sense than light rail.

Electricity is only less than a third of all energy consumption. 72% of the worlds energy is thermal based because it’s efficient to convert thermal energy into work without having to convert it to electricity. You convert to electricity you lose half to 2/3rds of the energy as waste heat. The carbon emissions from changing electric sources wont matter much since 75% of all GHG emissions come from non electric sources

I didn’t say that electric cars make sense. That’s a different debate. I said they made more sense for reducing GHGs than light rail IF you live in a region that gets its electricity from non-fossil fuels. If you don’t, then neither will do much to reduce GHGs.

Another consideration with vehicles is size reductions and natural/bio gas. In Japan and parts of Europe they have a class of sub compact cars “kae” which are very small, engines under 600cc and often get upwards of 80mpg. These can be used for commuting and short trips. Also with using natural gas you avoid many of the pollution issues associated with gas and diesel. Also, I agree with lazy reader, the huge issue with electrics is the energy used to produce the technology, also the passive energy losses in transmission, and maintenance. Honestly, unless something fundamentally changes with electrics their viability is limited at best.