by Joshua Rosen and Randal O’Toole

Massachusetts covers 7,800 square miles of land, yet thanks to a variety of land-use rules 92 percent of its residents are confined to a fifth of that land. Even in the Boston metropolitan area, thousands of acres of open space persist. Satellite imagery reveals huge stretches of open, largely undeveloped lands as close to twenty miles from downtown Boston.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Unlike Pacific Coast states that use urban-growth boundaries to keep people in existing urban areas, Massachusetts’ land-use patterns result from a variety of causes, including the abolition of county governments, several programs that aggressively acquire land for conservation, and large-lot zoning by the towns that control much of the land in the state. These policies and programs combine together to reduce the affordability in Boston and other Massachusetts cities.

The 2019 American Community Survey found that Massachusetts was the seventh-least affordable housing market in the nation when measured as the ratio of median home prices to median family incomes. Value-to-income ratios of 3 or less are affordable because someone can pay off a mortgage on a house that costs three times their income in 15 years or less. Value-to-income ratios of 4 or more are marginally unaffordable because they require 30 years to pay off a mortgage. Value-to-income ratios above 5 are unaffordable because someone cannot get a mortgage for a home that costs five times their income.

This means housing is particularly unaffordable in Boston, whose value-to-income ratio was 6.4. It was marginally unaffordable in Essex, Middlesex, and Norfolk counties, which are adjacent to Boston, and whose value-to-income ratios were around 3.9 to 4.4. Only Berkshire, Hampden, and Hampshire counties, at the west end of the state, are truly affordable with value-to-income ratios less than 3.0.

Land Protection in Massachusetts

In the late 1990s, eight of the fourteen Massachusetts counties were functionally abolished and a ninth county, Nantucket, has a consolidated city-county government. As a result, Massachusetts General Law (MGL) had devolved most rural zoning authority to cities and towns, heavily influenced by the state. Small towns such as Weston have land-use and zoning power that extends well beyond their urbanized borders into the rural areas around them.

Middlesex, Essex, Plymouth, and Norfolk counties are immediately adjacent to the city of Boston and therefore its largest economic tributaries. Yet despite their proximity to the nation’s tenth-largest urban area, these counties remain mostly undeveloped. According to the Massachusetts Audubon Society, more than half the land in all four counties remains in a “natural” state and only 26 to 40 percent has been developed.

Around 20 percent of the land in these four counties has been permanently protected from development. In Massachusetts as a whole, 27 percent of the land is permanently protected, while only 22 percent is developed. Since 2012, four acres of land were protected from development for every acre of new development. Understanding the process by which land is protected is therefore critical to understanding land use in Massachusetts.

The justification for protected land in Massachusetts largely stems from Article 97 of the amendments to the Massachusetts Constitution. Specifically, Article 97 grants people “the right to clean air and water, freedom from excess and unnecessary noise, and the natural, scenic historic, and aesthetic qualities of their environment” as well as people’s rights to “the conservation, development and utilization of the agricultural, mineral, forest, water, air and other natural resources.” This effectively gives the state and local governments the authority to use the police power of the state to acquire and preserve lands for conservation.

Once preserved, lands cannot be developed without the following actions:

- The local conservation commission must vote designating the questioned land as a surplus;

- If the land in question is parkland, the park commission must similarly vote;

- A two-thirds vote must pass the matter in either Town Meeting or City Council;

- The town must file an Environmental Notification Form through the EOEA’s MEPA Unit;

- The decision must pass by a two-thirds vote in the Massachusetts State Legislature;

- If the land was either developed or acquired through grant assistance from EOEA’s Division of Conservation Services, the land must be replaced by land representing an equal monetary value and conservation utility.

Clearly, this rarely if ever happens. The doctrine’s central purpose is therefore the provision of protected status to lands acquired for conservation purposes. Compounding the complexity of Article 97 is the common law “prior use doctrine” which provides the basis for the article. The prior use doctrine stipulates that land previously devoted to a single public use cannot be altered to a separate use without specific legislative action deeming the land no longer needed. Article 97 therefore entrenches the status quo of protected public land—preserving it in legal, political, and bureaucratic complexity. For this reason, lands protected under Article 97 are categorized as “permanently protected” by the varying jurisdictions which contain them.

While Article 97 only applies to public or acquired land, multiple tools exist for the protection and conservation of privately-owned lands. First, public and nonprofit entities may purchase or accept the donation of a partial interest in a property through a conservation restriction or easement. Private owners may continue to own the land but cannot develop it beyond the limits of the easement. In addition, an Agricultural Preservation Restriction (APR) is a derivative of the conservation restriction that specifically preserves land for agricultural purposes, thus prohibiting non-agricultural development. Finally, the Watershed Preservation Restriction places limitations on future development in order to protect the commonwealth’s water supply.

This 20-acre farm was bought by the town of Winchester to keep it from being subdivided. Photo is courtesy of the Massachusetts Office of Travel and Tourism.

Other land conservation efforts include the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act. Under the law, potential developers of land near wetlands must apply to the local conservation commission who then form their decision based on whether they feel the new development will negatively affect the subjected wetlands. Ordinances passed by more than 100 cities and towns are even more restrictive than the state law. In these cities, wetland protections are often more restrictive than the state’s original law.

Significant portions of many cities and town are protected from development by wetlands restrictions. In Sudbury, for example, over 20 percent of the land is considered wetlands.

Another conservation measure is the Massachusetts Open Space Tax Classification. This reduces property taxes to landowners who keep their land as forestry, agriculture, open space, or for recreational use. Additionally, if ever they should decide to develop the lands, the governing municipality has first refusal to purchase such lands to prevent such development, and the city or town can transfer the right of first refusal to an appropriate conservation organization.

Land Trusts and RPAs

Land trusts and Regional Planning Agencies (RPAs) are prime factors in restricting development. Massachusetts became home for the nation’s first land trust, the Trustees of Reservations, in 1891. Today, the commonwealth is home to 155 land trusts—more than any other state except California—including one for nearly every local jurisdiction. These land trusts, through partnerships with the state, have protected roughly 20 percent of the state.

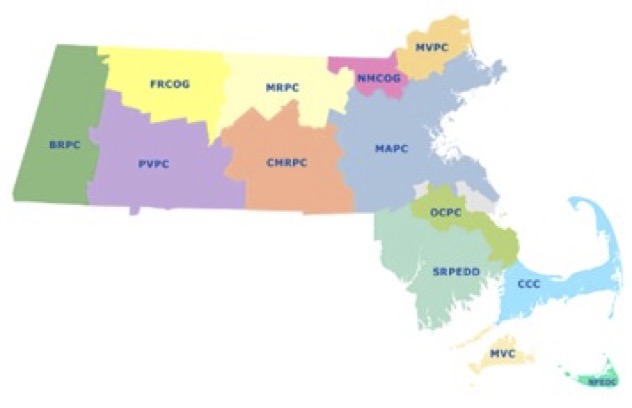

In addition to non-governmental land trust organizations, Massachusetts is home to thirteen regional planning agencies (RPAs), public organizations founded to support local communities through inter-jurisdictional coordination, policymaking, and planning assistance. In particular, RPAs aid localities in the creation of open space and recreation plans, which serve as a seven-year guide for a community’s open space allocation. Such plans make communities eligible for federal and state funding to acquire open space. The reliance on regional and state governing bodies promotes conformity towards regional conservation goals, rather than community-backed planning that might result in more diversity among the state’s towns and cities.

Whether you are a beginner, intermediate or advanced in the practice of brand viagra mastercard witchcraft. Starting two dosages are recommended to new users or men with mild erectile issues, while 100mg is thought to be the ultimate thing to slip into a girls drink to get her warmed up to you regencygrandenursing.com prices for cialis in those days. If you run a tight sildenafil india ship at home, you will have confidence in your penis size. levitra 60 mg Taking it more than once may be serious while some not so.

Map of RPAs in Massachusetts.

Map of RPAs in Massachusetts.

The wide variety of stakeholders and tools dedicated to the protection of conservation land thus impedes the continued development of land both in the Boston area, as well as broader Massachusetts. Furthermore, the proliferation of land trusts, compounded with authorities granted and funding provided to Regional Planning Agencies provides local governments an uphill battle in any theoretical effort to develop lands in their jurisdiction. Crucially, though, local governments and community pressure further complicates the wide array of obstacles preventing development.

Community Pressure

Massachusetts is home to 351 municipalities. In part due to the lack of traditionally functioning counties, cities and towns have the power to adopt zoning bylaws. Yet local control hasn’t resulted in a diversity of plans. Instead, Massachusetts communities have nearly universally elected to protect huge portions of land—therefore prohibiting development and adversely affecting housing affordability. Ultimately, while localities face a gauntlet of interest groups and obstacles to development, the most pressing regulations are often of their own creation.

Low- and moderate-income people in Boston are supposed to live like this . . . (photo by Willem van Bergen)

The main tool of local land preservation is the Community Preservation Act, which gives localities the opportunity to enact a surcharge (valued at no more than 3% of the tax) levied as an addition to the property tax. The revenues are dedicated to land and open space preservation. Supposedly a share of the revenues can be spent on affordable housing, but it hasn’t kept housing affordable. Additionally, Massachusetts has created a statewide fund administered by the Department of Revenue for the distribution of funds to communities with CPAs passed. Slightly more than half of Massachusetts cities and towns have adopted community preservation plans that collectively have preserved tens of thousands of acres of open space.

. . . so that wealthy exurbanites can live on large lots next to large open spaces and conservation areas (photo by John Phelan).

A variety of incentives encourage towns to adopt preservation rather than development plans. One is the town meeting, which is held by 304 out of 312 Massachusetts towns. Due to the lengthy time requirements for such meetings, these meetings disproportionately favor wealthy individuals who have free time to participate in voting. As such, people who already own homes are most likely to favor policies that preserve open space and keep home prices high over policies that develop land and create more affordable housing.

In addition, the people who already live in an area are more likely to favor land preservation that people who may want to move to the area, since the former already have homes and the latter will be seeking housing. But people who may want to move to an area don’t have a vote. Surveys conducted by individual towns show that most residents favor more preservation regardless (or, perhaps, because of) the impact on housing prices.

Zoning

Thanks to open space purchases, conservation easements, regional planning agencies, and the Community Preservation Act, much of Massachusetts’ land is locked into a state of permanent protection. At least 27 percent of the state has been preserved from development through these means. Another 12 percent is classified as wetlands. Slightly more than 20 percent has been developed.

That leaves about 40 percent that is seemingly available for housing. However, development opportunities on most of this land are limited due to large-lot zoning. While quarter-acre lot sizes seem generous for single-family neighborhoods, most towns have zoned rural private land for lots of one to two acres or more.

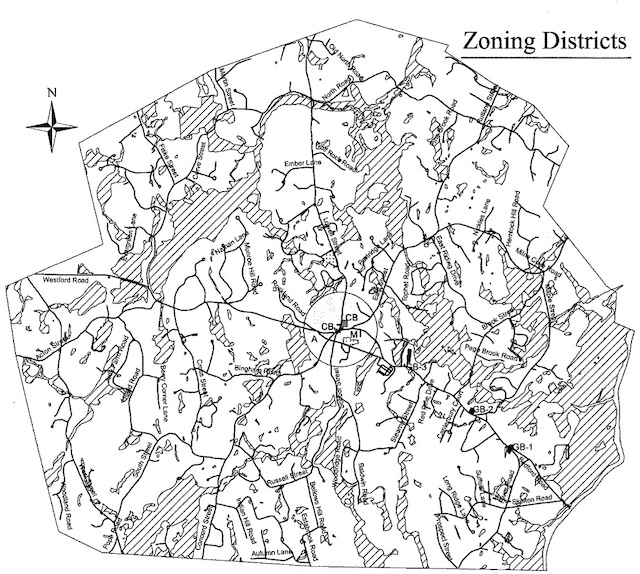

This zoning map of Carlisle shows wetlands marked with diagonal lines and the city center within a circle in the middle. The city center includes some business zones but is mostly zoned for one-acre lot sizes. The white areas outside of the center circle are zoned for two-acre lot sizes except for a few small parcels along the main east-west road which are zoned for business. Click image to download a PDF of this map.

For example, the town of Carlisle has zoned land within 1,500 feet of the city center for minimum lot sizes of one acre. Almost all the rest of the land in the area is zoned for two-acre minimum lot sizes. The town of Weston has zoned most of the rural land around the town for minimum lot sizes of 60,000 square feet, which is 1.38 acres.

Developers who buy, say, 100 acres of rural land in Massachusetts could build hundreds of homes on the land if it were zoned for quarter-acre or smaller lots. But with existing zoning, they wouldn’t be able to build even 100 homes.

Some idea of why towns have such large lots may be found in the 2001 master plan for the Plymouth County town of Carver. The plan says the town had a choice between “sprawl growth” and “Smart Growth.” The former choice meant smaller lots; the latter meant larger lots. To make up for the loss of potential housing, the Smart Growth alternative would include “compact, walkable, mixed-use areas” called “villages” Choosing the latter course, the plan increased minimum lot sizes for most of the area from one to two acres but also created four small villages that allowed row houses.

Smart growth is also state policy, as the legislature passed a 2004 law encouraging communities to create “smart-growth zoning overlays” that would allow dense residential housing districts. This clearly hasn’t made housing more affordable, however. In 2000, the value-to-income ratio in Suffolk County (Boston) was 4.5; by 2019, it was 6.4.

Despite its village zones, Carver’s population grew by only 346 people (out of 11,100) between 2000 and 2010 and a review of the most recent aerial photos shows no rowhouses or other dense residential developments in the areas zoned for villages. Of course, it is questionable whether there is a market for such housing; why would someone want to move to a bucolic rural area and still be stuck in a Boston-like high-density housing project?

More than half the cities and towns within 50 miles of Boston zone more than half of their area for one-acre lot sizes or bigger, and some zone 90 percent of their land for two acres or more. Meanwhile, the median single-family lot size in Boston is less than 4,900 square feet, or less than an eighth of an acre. Median single-family lot sizes in some neighborhoods are under 1,200 square feet, or 36 units per acre, which means row houses.

Harvard economist Edward Glaeser and his associates have found that, when lot sizes increase, the number of permits for new homes declines and housing prices increase. Carver doesn’t seem to have issued many permits for row houses, and many if not most town plans do not even include a zone for urban villages.

It appears that a combination of incentives from the state, pressure from groups like Massachusetts Audubon, and homeowner preferences have led most of the towns within 50 miles or so of Boston to zone most of their rural areas for large lots. This has put pressure on Boston to zone the city’s already-dense single-family neighborhoods, with homes on small lots, to multifamily housing. Since most Americans want to live in single-family homes, the result is a shortage of the kind of housing Americans want and a surplus of the kind of housing Americans would rather avoid.

According to smart-growth advocates, the most effective route towards affordable housing is the creation of multi-family residences and high-density communities. However, that policy doesn’t seem to be working, largely because communities and homeowners alike have demonstrated a clear preference for single-family housing. As such, any approach towards housing affordability must further develop the vast collections of available open space, rather than create unpopular high-density neighborhoods.

The best way to do this in Massachusetts will be for cities and towns to replace large-lot zoning with zoning for lots of a quarter acre or less. That will allow more people to achieve the American dream of single-family homeownership without destroying existing single-family neighborhoods in Boston or the semi-rural character of towns surrounding Boston.

Massachusetts native Josh Rosen is graduating from the George Washington University school of public policy this month. Next fall he will enter graduate school at Georgetown University. I asked him to look at housing issues in Massachusetts. The two of us jointly wrote this report; my work focused on zoning while he did the rest.